This biography is based on an interview with Robin Briant in 2017 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand project. The interviewer was Nora Lynch.

Contents

Early life: a farm girl at a Presbyterian school & working in a laboratory

Robin Briant was born in Gisborne and grew up on a farm in Patutahi. With five children born over 17 years, her mother worked hard running the household, particularly during World War II while her husband was commandeered to the Home Guard.

During her early education at Patutahi Primary School, Robin sat for a scholarship at Iona College—a Presbyterian girls’ school in Havelock North—where her close school friend Kay was to attend. While Robin’s two sisters attended the local high school, Robin went on to complete her secondary education at Iona, where she and her primary school friend soon drifted apart. The school was not particularly well suited to Robin, although she performed well, particularly in chemistry and her teacher encouraged her to attend university.

“It was a very restricted school–small numbers, designing young girls to be farmer’s wives, and provided us with no distant horizons and no great ambition.”

“It was neither wonderful or terrible, when I look back. I mean, in retrospect I sincerely wish I hadn’t been there; I wish I’d been at a local multi-cultural, mixed-gender—whatever you call them—schools. I never really sort of belonged in that community again.”

In 1957, after graduating from secondary school, Robin worked as a technician in the local laboratory where she completed three of the five training years in the role, including some study and an exam. Robin found working in the laboratory an interesting experience, during the days when all procedures were done by hand.

“There was nothing automated. You boiled up stuff, and made colours, and put it through the odd machine. We made our own egg media. Actually, we even made the IV fluids, if you can believe that. This much salt and this much glucose, and put it through the autoclave, filtered. Considering how things are so highly commercialised now, and done in such extreme conditions of hygiene, I sort of am a bit surprised about what we got away with. We did all the blood donors, all the phlebotomy; it was great, really but, I didn’t fancy myself doing it for the next 40 years.”

Looking for an alternative career choice, Robin considered completing a science or nursing degree. In the end, she was inspired towards medicine by a colleague who was completing his own medical training, and an encouraging local physician who promised her a stethoscope if she was accepted into medical school. Robin told her parents of her decision, uncertain how they would react.

“I thought they would be horrified. I had all these visions of being struck off, and never spoken to again. I don’t know why. I mean, how can you misjudge your parents, so? I guess it was just breaking out a bit. So, I had actually made my plan, almost so that it was unmakeable. They were starstruck; they just thought it was the most fantastic idea and were totally supportive.”

Medical school: moving to the centre of the world & gossiping during anatomy dissections

In 1960, after working her way through a physics textbook—a prerequisite subject she knew nothing about—Robin moved down to Dunedin to begin her medical intermediate training. The trip was long and arduous—a rail car from Gisborne to Wellington over a day, an overnight ferry to Lyttleton, and a train the next day to Dunedin, arriving about four o’clock in the afternoon. Met at the train station by her colleague from Gisborne, Robin then moved into St Margaret’s hostel where she lived for the next two years.

“It was a bit like an extension of boarding school when I was there, with a rather ferocious woman in charge. I thought it was incredibly liberal, because you were allowed out every night till 10 o’clock, which of course at boarding school you weren’t. Because I’d just gone back to that boarding school mode, I thought it was so liberal, where everyone else was kicking against the pricks, as it were. Yeah, it was really a place to live and eat. It didn’t have a tutorial program like the boy’s ones did, or anything like that.”

After leaving St Margaret’s, Robin flatted with non-medical students, moving into a new flat every year or so. On one occasion, she and her friends—both male and female—ignored the social norms, arranging to live together in a mixed flat.

“The landlord asked the university if it would be alright, or something, and all hell broke loose. So, we all had to go our separate ways.”

With several years’ work experience behind her, Robin had saved quite a bit of money by the time she moved to Dunedin and was able to support herself—aided with extra income from summer jobs—without needing to ask her parents for financial help. Coming from a small town, Robin loved the relative hustle and bustle of living in the lively, student-led Dunedin city.

“For me, going from a one-horse town, I thought it was definitely the centre of the world. I loved every minute of Dunedin.”

Robin was accepted into medical school after her first year of medical intermediate, with good marks in chemistry and zoology to make up for her passable knowledge of physics. She was one of about ten women on the first day of her medical school education.

“I only remember going into the anatomy dissection room, and the guy on the table next to us fainting, and that terrible smell of formaldehyde. Our class seemed to be endlessly berated as being very ordinary and hopeless by various staff, one in particular, but we actually produced quite a few stellar people, in which I don’t include myself. There are a lot of people who have been in the top of all sorts of things.”

Medical school held lots of opportunities for socialising. The students often went to the Town Hall dances or the Freshers’ Hops—social events with dancing and music. Each of the university hostels held their own balls, medical classes had get-togethers, and the boys would often go to the pub. Women would not go out to drink, as this was generally disapproved of, although the women Robin lived with would often invite someone over for dinner and have a bottle of wine together. Despite being a few years older than most of the other students, Robin had no trouble making friends within her medical school class.

“I had a few friends. I spent most of my anatomy time, which was a lot—five afternoons a week, for five terms—I spent most of that talking. I didn’t do any dissection, hardly. Dorothy and I and Yogesh Patel were on one half of one cadaver, and Yogesh spent his time studying his books, and Dorothy loved doing the dissection, and was very good at it. So, she did that, and I gossiped; I got to know every single person in the class. I could probably still identify them.”

Robin and the other women students encountered some sexist behaviour during their medical school education, particularly during the anatomy classes, where they worked more closely with the teachers and other students.

“The anatomy tutors who wandered around amongst the cadavers and the students—some of them were particularly sexist, and I thought that’s how the world worked; you just got on with it. It was years before my consciousness was raised, I have to say. No, there were one or two notoriously unpleasant people—not so much putting down, as just being plain sexually rude and suggestive.”

Despite the challenges of the dissection room, Robin was quite good at anatomy, whereas she disliked biochemistry. As she progressed through her training, she acquired a great deal of knowledge while she still lacked clinic acumen. Students were taught in large groups, which could make learning difficult.

“You’d have twenty people in one little clinic room with Noffie Lewis demonstrating how to palpate the abdomen. Being one of the tallest ones, I had to be at the back, and you can never really see anything much. I didn’t really engage that well. I was keen to, but it didn’t feel that the climate and the environment was really conducive to that. We did have sub-groups of the twenty divided into twos and threes all alphabetically. I was with two people that I didn’t really like.”

Robin’s sixth year training in Auckland was more hands-on, working in smaller groups, and she learnt a lot that year, particularly from her tutor Gordon Nicolson. After a year spent working across three Auckland hospitals, Robin returned for Dunedin for her final exams, and then her graduation ceremony in May.

“It was a lovely ball. Practically all the staff and their wives were there. My father went; he took one of his friends with him. That was so exciting, because my parents had hardly ever travelled anywhere, and they didn’t go to Dunedin all the time I was there. One of my little brothers was graduating from school on the very same week—my mother went to that, so Dad and his mate came down to Dunedin and we had a lovely time showing them around and having dinners together and things. I just remember it was quite a high time.”

After graduation: house surgeon training & the nightmare run

After graduating from medical school in 1966, Robin spent two years working as a house surgeon in Auckland to gain her medical registration. She lived in residence along Park Road, which was an old private hospital. Robin’s great-aunt had worked as a matron many years before in the nearby Huia private hospital.

“I did nothing but work and sleep and occasionally visit my relatives and a few friends.”

The house surgeons were given experience in a range of medical and surgical specialties. Particularly terrified of taking clinic responsibility for anaesthetising patients, Robin strategically chose to complete her anaesthetic run early in the year when she knew she would receive some supervision.

“At that point, in Auckland hospitals, the house surgeons did nearly all the acute anaesthetics, if you can believe it. I was petrified, having done two weeks in an operating theatre observing an anaesthetist, that I would kill somebody. I just couldn’t bear the thought of having to do that unsupervised. It was the most horrendously dangerous thing I can imagine. So, there were a number of these run groups that had anaesthetics as a first run, so I picked only those. So, by the end of three months I was quite zippy with my endotracheal tubes, and putting people to sleep, and waking them up again.”

Robin’s second year of house surgeon training began with a run in the casualty department.

“The house surgeon year began at midnight on 1 January. So, Tony McCallum was the ED doc up until midnight that night; I rolled up one minute to 12 and he said, “it’s very quiet—you’ll have a good night”. He walked out and all hell broke loose shortly after. I just remember being beside myself that first night; New Year’s Eve, as you can imagine. It just went bonkers. We had a couple of big hospital security chaps hanging around; I think they were protecting the patients from me, as much as the other way around, by the end of that night.”

Robin remembers her time in Critical Care—then known as the Respiratory Unit—as her nightmare run. She worked as one of only three doctors in an old brick building that was originally used during the polio epidemic to ventilate people with paralysed respiratory muscles, including one woman was in hospital for a decade or two before she could leave. The Unit had to be staffed continuously.

“The total medical staff was Matt Spence—who was considered to be a tyrant, and he and I got on like a house on fire, I don’t know what that says about me—Tony Hewlett, who was the registrar, and moi.”

“Tony Hewlett and I, one or other of us slept there the whole time—not together. There was one room, and if he wasn’t on, I was. We were receiving these horrendously ill people, and Matt was on the end of the phone, and he would come in very readily, but it took a while—it was excruciating, scary—but I learned such a lot. So, a weekend started on Friday morning, you were allowed to go out and have lunch if you could find someone to relieve you, which you usually could, but not always. Saturday, Sunday, Sunday night, Monday; you’re probably allowed to leave about one o’clock, if you’re lucky. That was my nightmare run, in a sense, but you learn so much in those sorts of situations.”

After completing a Psychiatry run, Robin worked as a medical registrar at Greenlane Hospital for the following year. Her inspiration for a career in internal medicine came from her colleagues, including Drs John Scott, Mike Gilmore, Gavin Kellaway, Gavin Glasgow, Keith Eyre, Kaye Ibbertson, and Derek North. However, her decision was also driven by an aversion for surgery and anaesthetics, and internal medicine was a difficult choice with her limited background in the specialty. Robin worked very hard, hoping to pass her college exam after just one year.

“I knew almost nothing about medicine; I hadn’t done a medicine run since early on, and I was completely overwhelmed.”

“I really probably drove myself a bit hard. It was a one-in-three call roster. I lived out, we got called in quite a lot, if you ever got home. The other nights I had my Harrison’s at the ready. I didn’t have much of a life; I was exhausted, and when it was time in the mid-winter to apply for another registrar job, I didn’t bother.”

Living in England: a research role & earning an MD

At the end of 1968, Robin decided to take a break and work as a locum general practitioner for a few months, before passing her Royal Australasian College of Physician exams in February—no mean feat—and then heading overseas to England. However, after a few months of travelling with friends, she discovered that her RACP membership was worthless in the UK, and that to find a good job in London she would need to complete her Membership with the Royal College of Physicians.

Robin studied for her MRCP as fast as possible and was then able to find work as a house officer in Hammersmith Hospital. Her employer, Colin Dollery, was a clinician with a research laboratory, and he offered Robin a research position funded by the Wellcome Trust, with a registrar attachment. Robin was inspired by the role, and while working at Hammersmith she decided to complete her MD thesis through the University of Otago.

“Colin was very exacting and drove you quite hard, but he was a fantastic leader and mentor and I had excellent experience in his department.”

“I really liked him, and we got on well, and he was sort of leading clinical pharmacologist in Britain, or he thought he was. There might have been others who thought they were, too. There were several others who were equal leading, but he was the most aggressive and self-promoting. So, he had a big research group of great people, and again another huge learning experience.”

Robin spent the next four years living and working in England, travelling throughout Europe whenever she had the opportunity. Her relatives in Scotland gave her an historical tour of the region, and then one day, much to Robin’s excitement, her parents announced that they’d had enough of farming, were passing on the responsibilities to Robin’s brothers, and would be coming to visit her in England.

“I rented a little house in Richmond on the Thames, with another ogress as landlady. I seem to be followed in my life by ogresses, with the Headmistress at Iona, the warden at St Margaret’s, and then this one, who treated my mother disgustingly. My mother was so careful and house-proud—but we needed to have her cleaner to come in in case her furniture wasn’t cleaned properly. Anyway, that was fine. They had a fabulous time, too; the travelled quite a lot, and the three of us went to Europe together in my tiny, ancient VW Beetle. They had such a brilliant time, and I did, too. It was the best time.”

In 1973, almost exactly four years to the day after she arrived, Robin sent her MD thesis back to Otago to be assessed.

“In those days, it was in covers straight away; there’s no giving a draft and having to word process it all; it was typed on a non-electric type-writer; it was there, or it wasn’t there. It was there enough, so I graduated MD.”

Standing at the crossroads, and uncertain whether she wanted to live in England for the rest of her life, Robin decided she would go back home and see New Zealand after a few years away. Unhurried, she took a three-month journey home and visited all sorts of interesting places along the way.

Returning to New Zealand: a love affair for clinical practice and teaching

“I’d been here about five minutes and decided that I was staying.”

Back in New Zealand, Robin’s career expanded rapidly, as she straddled responsibilities as a physician at Auckland Hospital with an academic and teaching role through the University of Auckland. However, her love for patient care always came first, providing the building blocks for her expanding career path.

“Clinical care of patients was the centre of my life as a doctor. From the first I saw myself as primarily a hospital doctor—the other jobs were all side affairs.”

Now equipped with specialty knowledge in hypertension from her time at Hammersmith Hospital, Robin ran weekly outpatient clinics for both general medicine and hypertension. She particularly enjoyed the collegial nature of the working environment in the wards, where the hospital’s approach to patient care allowed patients to remain with the same clinicians for the duration of their stay. She developed an excellent working relationship with Dr Gavin Kellaway, and the two worked together as part of a team for many years.

“I believe our ward was a safe haven for some of the junior medical and nursing staff who had found the going difficult in less supportive environments. It was also the go-to ward for a moderate number of patients with difficult chronic illnesses who we followed as outpatients and who always came back to our ward if admitted as inpatients; this continuity of care is one of the features often missing in modern healthcare setups. I feel it is vitally important.”

Clinical teaching was an ongoing part of Robin’s career as a physician, and a role that she particularly enjoyed. At the beginning of the year, each team would include a group of fourth year medical students learning the fundamental of patient assessment—how to get comfortable with the sick, how to take the history of their illness to understand what was going on for them, and how to examine their bodies. Later in the year, the team would be expanded by six slightly more advanced students, who were there to widen their knowledge of internal medicine and put into practice those recently learnt skills and their accumulating knowledge.

“I really valued this time, gently guiding the anxious young in this important time of their careers.”

“Over the course of so many clinical years I got to know many students in this quite close learning encounter, and enjoyed challenging them to do better, and mentoring those who found it all a bit too much.”

Alongside her work as a clinician, Robin climbed the academic ladder starting at the lowest clinical lecturer scale in 1974 and later rising to Clinical Associate Professor in Clinical Pharmacology with the University of Auckland’s School of Medicine—a role that required both a research and a teaching component. While Robin had a firm foundation in clinical pharmacology from her research experience in Hammersmith, back in New Zealand Robin was now faced with the challenging task of teaching undergraduate students the study of drugs in humans. Despite her lack of prior teaching experience, Robin rose to the challenge, teaching herself the art of teaching.

“It was another pleasure delivering a coherent and practical course on a subject that is so central to the work of most doctors for the rest of their working lives.”

In contrast to her love of teaching, in time Robin realised that she did not particularly enjoy the practicalities of research, and in 1980 she decided to drop the research component of her academic career in favour of her many other clinical and teaching interests.

“I’ve got here and I thought, “oh God I’ve gone through the whole circle; I’ve started in the lab, I’ve done all these years, and I’m back in the damned lab again”, which was fine for a wee while.”

“I thought, “I’m not a researcher, and I can’t bear this, having to apply for grants every five minutes”.”

Abortion and women’s rights

Robin developed an interest in women’s rights during her early career, particularly around family planning. She and the other female students had been introduced to the Medical Women’s Association on the day that they graduated from medical school. However, it wasn’t until later, after returning to Auckland with some overseas perspective, that Robin became more involved in the movement.

“They were nearly all lovely elderly women who had seldom practiced, or had long given up, and they had lunch together once or twice year. Marilyn Scott and Morag Hardy, took MWA by the scruff of the neck and brought it into the 21st Century—or the 20th anyway—and then they made me join and get involved more.”

With a newfound awareness of women’s rights around abortion, Robin offered her services to Auckland Medical Aid Centre, where she soon found herself providing abortion services. The experience taught her a lot about women’s issues, and she also learnt how a clinic can operate around the patient’s best interests rather than the conveniences of the medical staff.

“In England, when I was there, the abortion law had been liberalised, and I had, through friends, realised—which I had never before—that it was an important part of women’s health, and choices. I’d always thought, “oh well if you have contraception you can prevent being pregnant”, which didn’t actually a quite work that way, I discovered.”

“When the clinic started here, I offered myself. I was still just doing mostly research at Med school, and I had time on my hands. I offered myself as one of the counselling doctors. They said, “we’ve got enough, but we haven’t got enough operating docs”. I said, “I couldn’t possibly do that”, but anyway transpired that I was lined up and trained by Dr Wolner, and I did the Saturday list there.”

“It was local anaesthetic, cervical block, and suction. There I met Sandra Coney and a lot of other feminist women, really strongly identifying as feminists, and I learned a lot from there. I learned a lot in that clinic of patient-centredness—we organised the service around that person. Not too difficult if you’ve got a single focus, and I appreciate much more difficult in almost everything else, but I don’t think we’ve got anywhere near it in most public medicine.”

World Vision & the anti-nuclear movement

“I guess I’ve had that underlying social justice philosophy, and certainly feeling that we have so much here, and others have so little.”

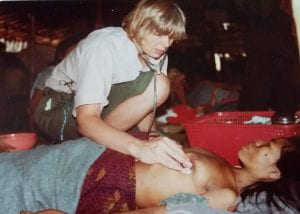

In the summer of 1979, after finishing her research position, Robin spent some time in Thailand with World Vision, where she was one of three doctors working with a team of nurses.

“There was a crisis for Cambodians. It was the end of the Pol Pot era. Pol Pot had been taken out by Vietnam-backed troops, and the population near the Thai border was taking the opportunity to move, not knowing what was coming ahead. They’d survived those years in the killing fields, and they were pouring across the border into Thailand.”

“The first day we went to one camp briefly, but that was sort of well-established, and we were detailed to go to one—Khao-I-Dang—that was just establishing. Literally, it was a piece of clearing in a scrub—there were piles of red plastic buckets, and there were Thai men building us a ward out of bamboo and plastic., They subsequently built a hospital of ten wards. I looked after the ward that we developed; we had one hundred beds in it. The other two docs did ambulatory work. The people were survivors, but they were malnourished, and on the way across the border there were bandits, thieves and there were mines, and there was malaria. So, they arrived and most of them in a terrible state but got better really quickly. It was extraordinary to see people almost on death’s door with Falciparum malaria, cured with Quinine in days and off they went.”

Robin found that she had exactly the right skills to work in challenging conditions with limited equipment.

“There was no lab, no x-ray, no electricity, and a limited array of drugs, but lots of Quinine, and antibiotics, and fluids. I think I got on better than most people who had come from firster worlds—I mean, people arrived with their cardiac monitors and stuff; I could rely on my well-honed clinical assessment. I also did the anaesthetics, to start with, before an anaesthetist arrived, because somebody had brought a nice operating theatre tent, but they forgot to bring out an anaesthetist. So, that’s why I was really pleased with my old anaesthetic skills.”

Later, Robin’s involvement with social justice organisations expanded, first as an early member and then later the Chair of New Zealand’s branch of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War.

“With the anti-nuke movement, I guess again, some of my friends from Dunedin days really introduced me to war issues. Going back even further; when I was a small child, I was born just literally the days after or before—I forget which—the Second World War was declared. So, my childhood had this sort of feeling of war in the background. I didn’t really quite understand it, but there was sadness and horrible things going on, and my father away quite a bit. Then, again you think it’s just part of the way the world works, I suppose. I began to think about those things. I joined the Peace Foundation early when it developed, in Auckland; been involved with that ever since.”

“Then, IPPNW sprang up. That started in the US and the USSR, but it rapidly spread, and Ian Prior—who was a public health physician in Wellington and had lots of international contacts—he brought it to New Zealand. He got Derek North involved, and Derek was the president initially, or Chairperson, for the country. Derek had lots of charisma, and brought people in, and as a movement it grew hugely and I got involved in it relatively early in New Zealand. Anyway, then I seemed to be next in line to be Chair. At its peak 20 per cent of New Zealand doctors belonged to IPPNW. Internationally it was fantastic group of people. I went to lot of its conferences. I just loved them on account of the really interesting and friendly doctors who made up its ranks. I loved them so much more than medical ones. A real learning explosion for me.”

“Unfortunately, although the nuclear threat is really still very large, the end of the Cold War, the awareness of such things dropped off, and in fact the New Zealand branch has folded its tent. Nick Wilson, Public Health Physician in Wellington took over the Chair for a long time, and worked really hard, and was a very good lobbyist in Wellington with Government, but even he couldn’t really maintain energy in it. So, it’s still an international movement, and Australia is still quite active, but we don’t have a chapter.”

Going it alone—consulting physician in Auckland

In 1980, now freed from her research responsibilities with the University of Auckland, Robin decided to start her own Specialist Consulting practice in inner-city Auckland. She worked out of her large suburban house, dedicating the bottom floor to her practice. She employed a part-time secretary, promoted herself with the GPs, and found she had enough work to keep her busy for three half days a week, spending the remainder of her time as a physician and clinical teacher at Auckland Hospital.

“I guess I was anxious that I would be clinically up to it in my private practice. It was a different way of functioning, especially by yourself.”

“I loved it, apart from having all the dictating. Dictating does get you down a bit; dictating all your letters, reports, and things. I wasn’t one of those who could get my thoughts together and do it with the patient present, and indeed I didn’t do it between patients. Some people I know booked themselves an extra ten minutes. I needed to sit down at the end of the day, clear my head and start again and work through it, and maybe think about some things, and look up a few things, and phone a few people, and I could never complete my reports in five minutes—two minutes—like the surgeons do.”

“I did like that one-to-one, or one-to-two with you, the referring GP, and the patient, and not have numerous flunkies in between all telling the patient different things.”

Chair of the Medical Council of New Zealand & earning a CBE

By 1984, Robin had a wealth of experience behind her that included medical research, humanitarian efforts, and women’s rights. She found herself as a member of the Medical Council—a nominee of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Gavin Glasgow as well as Michael Gilmore, who was retiring from the role, put Robin’s name forward as an alternative option to an older male who had his eye on the position.

“They sort of, bulldozed the college into nominating me as they knew it was time for a change. I remember that I heard all these rumours that it was going to be terrible, because I was a—what was the word? Rampant feminist.”

“When I heard the rumour, I said, “real feminists would be turning over in their grave if they heard that”, but anyway, I got nominated, and I kept my head down and my mouth closed for the first meeting or two. I didn’t make a big issue about things, except when the Chair kept calling us to order as “gentlemen”. I quietly took him aside at one point and suggested that he use some other term. He said, “but what can I say?” I said, “well you could say, colleagues”. He said, “okay”. He did that, but I don’t think it had ever gone through his head. He’d been a Chair of all sorts of important things, and they were men, and he said, gentlemen.”

In 1990 Robin was elected as Chair of the Medical Council. As the first woman in the role, Robin was relieved to now have the support of two other women doctors and a female lay person on the Council, who brought different views to the organisation. The Medical Council then began investigating certain medical complains a bit more deeply than perhaps they had previously.

“Chair of Council was a really hard job; really, really. There were lots of reasons. I was living in Auckland, and it was based in Wellington, so there was a lot of travel back and forth. It still did the disciplinary hearings for serious complaints—there was no new Act like there is now. All the serious matters that might amount to a striking off offence came to us, and at that stage there was a lot of complaints of prescribing controlled drugs for addicts—quite a number of doctors who were clearly breaking the law, and probably making a large amount of money, and certainly feeding the addict population. We recognised that there were complaints of a sexual matter that were starting to come forward, and so we did a big project on sexual involvement of doctors with their patients. A lot of complaints started to come in, previously there had been some come but they tended to get shoved aside as no one really understood the issues.”

“I remember early on, there was a complaint brought to the attention of the Council by the Preliminary Proceedings Committee, which was the investigative committee of Council. It was a woman who was complaining about some very uncomfortable examination in her nether regions, and the Chair of PPC had explained to her that the doctor would have just been feeling for the nodes in her groin, which is a legitimate indeed necessary thing to do in the right circumstances. But there was no investigation into the actual circumstances. So the complaint was dismissed… Those things begin to raise questions in your mind; what is being dismissed without ever being properly investigated? Anyway, there were some very high-profile cases. There were always two sides to every story, and two groups of supporters for the patient and the doctor. I felt myself in the middle of that. There was quite a lot of media attention; that wasn’t always very easy to handle.”

“Then, there was the development of other specialties wanting to be registered, and the old colleges getting more and more strict about who they would endorse, and what the process was for overseas people to get in. There were a number of rather tense moments with college Chairs and things like that. I just found it all quite difficult. During that time, my young sister died, as well. So, that didn’t help, as you can imagine. So, I was really pleased to finish with being the Chair. I can’t say I regret doing it; again, it was an experience that was great, in many ways, but just took a lot out of me.”

Robin’s hard work in the role was rewarded when in 1995 she was received a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire award, for her services to medicine.

“It was quite exciting at the time. There’d be ten people in the world who remember I have a CBE—I don’t use it ever. Well, no that’s not quite true; on rare occasions when I think it might impress somebody that needs impressing…”

“Cath Tizard was the Governor-General, and I knew her personally through a mutual friend, and the Labour Party, and we’d actually travelled together before that, on holiday. So, she invited me and a couple of friends, and my two nieces to stay in Government House in Wellington for the occasion. So, that was exciting. Then I had a party in Wellington at another friend’s house, the night or two afterwards. It was lovely. It was a good moment, but it’s nice to have it, I suppose, but I don’t know quite what to do with it. You’re not supposed to wear the medals, I don’t think.”

“I had a medal dinner one evening after Tony Baird and Rod Ellis-Pegler got their gongs, and all the wives brought their nursing medals and things, and we had a jolly evening.”

In 1996, Robin decided to quit the Medical Council. She enjoyed the liberation that this gave her, and soon decided to remove other sources of stress from her life, giving her the space to reflect on what really was important to her.

“I thought, it’s quite nice quitting things; I suddenly had a bit of extra time. I still had my hospital appointment, and I was still doing my teaching. Then, the university decided we had to have some sort of reviews, and I said, “I’m not having a review—I refuse—after all these years I’m not going to be reviewed, so I shall resign”. So, that was I think ’97, I quit that.”

“I did a couple of units in art history to fill in the time. My mother dropped dead at 70, without any hint of illness, and I thought, “oh what if I drop dead on my ward round—I’ve got nothing but these bloody ward rounds for all these years, in worse and worse circumstances—nothing seems to have improved, really”. So, I thought “I’ll resign before I turn 60”. So, I went to see John Henley, who was a clinical director, and he said, “oh good—I must go and tell Mike Rackley (the Manager of the Dept of Medicine)”. Perhaps he didn’t say that, but he certainly didn’t try to discourage me, which I was a bit offended by. Anyway, so I quit the Hospital before I was 60.”

Into retirement: coordinating the Auckland Safety Study & Médecins Sans Frontières

By 1999, Robin had given up most of her employment when she was approached by Peter Davis and offered the role of Clinical Director of a public health quality and improvement study throughout New Zealand. The study took two years to complete and remains a landmark study of adverse events in New Zealand hospitals.

Around this time, a health crisis allowed Robin to put her life in perspective and gave her motivation to tick off some more experiences from her bucket list. Despite facing some complications from breast cancer treatment, Robin managed to squeeze in some more overseas experiences, travelling around Africa in a little van and a tent with a few friends. Not content with travelling for her own benefit, in 2003 Robin sold her house and began working with Médecins Sans Frontières—returning to the social justice themes that had prevailed throughout her career.

“I thought, “I’ve survived the breast cancer, I’d better pull my finger out and actually do what I want to do”. I couldn’t decide on an organisation to work with. Some of them are very agenda-driven. I went to a talk by somebody from MSF. I just thought that I wouldn’t be able to work with them, because they’re all sort of in the middle of war zones, and you have to be an anaesthetist or a trauma surgeon, or something. From the talk I understood the breadth of their work, and their humanitarian medical principles. So, I got accepted by them.”

“They weren’t driven by anybody’s agenda; they don’t take money from governments, they don’t take it from corporations or churches or anything. So, it’s purely humanitarian-driven, bringing medical, nursing and other assistance to people in distress from conflict, epidemic, or natural disaster. I thought I’d be too old, but being older was actually good, and my energy level was alright. I thought, I won’t be able to cope—I won’t be so young—but the young got more tired than I did, as it happened.”

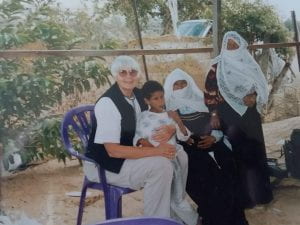

Robin completed three different placements over the years, returning to New Zealand in between to recuperate.

“A Palestinian one for MSF for just on a year, half in Jenin in the West Bank, and half in the Gaza Strip. I came back for a while; I was a bit traumatised, I suppose. I actually did some time in Rarotonga Hospital as the locum physician. It just happened that they were looking for a locum, and I went there for three months. There were a few family things I had to do. And then I went to a place that I’d never heard of called Abkhazia, which is a little north Caucasus republic on the edge of the Black Sea, surrounded by Russia in the north, and Georgia on one side—the Black Sea the other side, and Turkey below. It had gone through a nasty little war of independence from Georgia, after Georgia was liberated from Soviet Union.”

“MSF was running a few programs there; kind of primary care. A lot of older people were left isolated after their families either died or fled, because most of the Georgians living there had to flee back over to Georgia, even though they’d been there for generations. There was an attempt at a palliative care program where we had to keep the morphine in the bank because of the attitudes around drugs., I was the manager of a big tuberculosis programme where there was a large amount of drug-resistant TB engendered by their ancient medical system, which had ground almost to a halt. And drug abuse, and imprisonment, and people buying a month’s worth of INH and feeling better. That was absolutely fascinating; really interesting medicine.”

“Then, I went to Pakistan, after there’d been a big earthquake in 2005. I went there in early 2006, not to be involved with the earthquake, but MSF had now got emergency access to Pakistan, which had been always difficult for them to get into and wanted to stay there as it was getting very unstable politically MSF thought a Tuberculosis program would be good; there was nobody treating drug-resistant TB there. My job was to explore the nature and spread of the problem, and where we should set up a program. So, I had a young man as my assistant for language and getting access to people, and I had a driver, and I travelled a lot in Pakistan, meeting up with anyone who did anything with TB., We weren’t allowed to go into the border zones, or many other insecure areas, it’s a huge country, I spent most of my time in the North-west Frontier region.”

“Once I’d finished there—and I recommended that TB programme concentrating on drug-resistant cases would be a good thing, and we should be based in Peshawar—I still had quite a bit of time left on my visa, and our field coordinator from up in a mountain clinic had left early. So, I went up there to the Kagan Valley and finished that project till the Ministry of Health took it back over again. Then, MSF decided to throw my report in the bin, I think. They moved everybody out of Pakistan. They’d run out of money at the time. I was a bit disappointed. I sort of got the pip, a bit. I did intend to return; not to Pakistan, but into the field. Then, I got a dog, and I didn’t want to leave him behind.”

A new life in Gisborne: hospital physician & working in palliative care

At the end of 2006, Robin moved down to Gisborne to be close to her family, where she bought herself a house in Wainui Beach. The Gisborne Hospital had just lost a physician, and Robin soon found herself back doing ward rounds and being on-call one in three, supported only by first year house surgeons and no registrars. After several years, Robin took over diabetes management for the region, until in 2012 Robin moved into palliative care as the Hospice Tairawhiti Clinical Leader, where she agree to work for a maximum of one year.

“I actually got actively depressed towards the end of that. I had a period of depression after my sister died, and the stress around the Council stuff then. I did go onto anti-depressant medication in that earlier period, so I just didn’t really want to go on with care of the dying. I guess if you train in palliative care, you learn better the skills of managing so much dying. I thought, “I’ve been a physician—people die all the time in our care”. It wasn’t the same; they would come into the ward acutely ill, and die, and you didn’t perhaps get a chance to know them. Whereas, I would have time to develop a relationship with these ones; there were a lot of people very young, and a lot of people my age, and I found it very sad. So, I did leave when I said I would, and subsequently I have found it in my heart to go back and do fill-in josb when they need me; it’ll just be for a few weeks at a time. I find that I like that. I can think at a slow pace, and be beside people who are dying—a little bit beside them—and then I can return to my other life. So, I’m okay about it.”

Reflections: family & advice for students

Robin looks back fondly on her family who supported her from when she was a young child and into adulthood.

“When I went to boarding school, we had to write to our parents every Sunday, and my parents took up the role of writing every Sunday as well. So, until the days they died—which was only two weeks apart in the end, when I was 40—if any of us weren’t living locally, they wrote to us every Sunday. So, my sister married and went to live in New Plymouth. My young sister was in Whangarei. The boys were travelling or whatever. I was in Auckland or wherever; all these letters were written, and we all wrote back, almost without fail. It’s extraordinary to think my father died on 2 August, and my mother on 20 August, and the letters stopped.”

“I might have made more effort to get myself a husband; might have. I don’t know. I’ve managed perfectly without, but the idea of a companion is quite compelling, especially in your old age. I really didn’t feel I had room in my life, and I didn’t meet anyone I could live with for the rest of my life—and vice versa.”

Robin reflects kindly on her career working with so many medical students who were keen to learn, although she worries about the quality of medical education these days.

“When I think back, I ended med school fiscally-neutral, rather than with a burden of $100,000 debt, or something. I just can’t believe how I would have coped with that. I don’t think I could have. So, I lived in the best of times, and where clinical skills were so important, and I feel the loss of those is happening. I feel really concerned about that; the young ones going through the hospital. I don’t see a lot of them nowadays, but even three or four years ago they weren’t up to it.”

“Medical students who are always interested are a challenge and a delight, and it’s wonderful having known so many, nearly everywhere. If I want to refer someone from Gisborne, I nearly always find a specialist at the end of the phone who knows my name, and that’s been so valuable.”