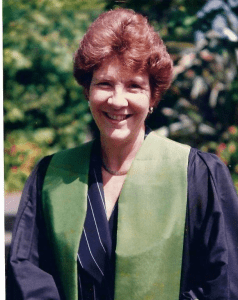

1968 graduate

This biography is based on an interview between Cindy Farquhar and Wendy Hadden in 2018 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project.

Contents

Early life: born on an auspicious day

Wendy Fitzwilliam was born in 1943 at El Nido, a birthing home near the Leith in Dunedin, where her mother (Noeline Rira Hardy) had a private obstetrician. The obstetrician was ‘old’ Doctor Gerald Fitzgerald, who was filling in for his son, ‘young’ Doctor Fitzgerald. Wendy has one brother, who is six years her junior.

Wendy’s maternal grandfather was the captain of a ship (Captain Hardy), so Noeline moved around New Zealand a lot as a child, though she spent most of her childhood in Devonport. Captain Hardy was meant to become the harbour master in Auckland, but he died of pneumonia in Dunedin Harbour in winter, 1926. He left Wendy’s grandmother as a widow, with five children, of whom Wendy’s mother was the middle daughter. Wendy’s father (Edward Gordon Fitzwilliam) was an engineer who worked with cars and trucks.

When Wendy’s parents got married, they moved from Dunedin to Hamilton, where they lived for about ten years, until the war came and Wendy’s father went to build air drones in Singapore and Malaysia as part of the New Zealand squadron of the air force. He came home after Singapore fell, and was one of the last out of the country in 1942. Wendy’s mother did not know whether he had got out or if he was a prisoner until he called six weeks later from Christchurch to tell her that he was alright and that he was home.

Once Edward returned, Noeline became pregnant, and Wendy was born in 1943. She was born on the same day that Pantelleria, in Italy, gave in (June 11, 1943). This was one of the early wins for the Allies. The thought was always that she should have been called Pantelleria, but she is glad that she was not, because she thinks that she would have been called ‘Panty’.

The decision to go into medicine: strongly encouraged by Otago Girls’ High School

Wendy, who attended Otago Girls’ High School, knew that she wanted to be a doctor from a young age. “And because it was Otago Girls’ High School who produced the first woman doctor and the first woman lawyer it was sort of expected that the girls who did well in the class were going to go into medicine or law. So I thought medicine was for me. So from about the fourth form I wanted to do medicine and set my sights on it and did science subjects where I could, and was dux of school.” Wendy did have one uncle in England who was a doctor, but she did not know much about him.

Wendy believes that she had a good education. Otago Girls’ High School did offer physics, but in Wendy’s year, the physics teacher was on maternity leave. Thus, her class learnt chemistry and biology but did not address physics. Some girls got sent to the boys’ school to study physics, but Wendy studied Latin instead. She appreciated that she needed physics to go into medicine, so she went to King Edward Technical College to learn from the teachers there, but this was relatively basic compared with what the boys learnt. While at school, she played hockey and cricket, did embroidery, and participated in debating with Otago Boys’ High School. Her interaction with the boys through debating meant that she was able to attend lots of social events with the boys.

Wendy’s mother was not very keen on her going into medicine. She told Wendy that “it’d be nice to marry a doctor, but I don’t want you being one”. Wendy believes that her mother thought it would be hard for a woman to be a doctor, particularly if she wanted to have a family. She suggested that Wendy do something “nice, like home science”. So Wendy listened to her advice and looked around the home science school to see what was on offer. But when she saw that they were ironing hankies, she told her mother she did not need to learn how to do that, and that she was sticking with medicine. Wendy’s father, meanwhile, was quite enthusiastic about Wendy’s choice. “Oh, he sort of said, “Oh let her have a try, she probably won’t get in, don’t worry.” To my mother.” In the end, however, Wendy’s mother was “chuffed” that she did do medicine.

Medical intermediate: jubilant when she made it into medicine

Wendy stayed living at home for her medical intermediate year (1962). The friends around her did the same thing and she used to walk to university with her neighbour, so she did not feel as though she was missing out on any university experiences. It was cold and icy running down the hill; “You had to learn where the ice patches were so you didn’t fall over.” Although the students at the halls of residence partied lots, “We kept on doing the things that we’d usually done, living the same way. Staying friends with the girls that I’d gone to school with and the boys.” She lived just above the university, so she would walk down the hill for the first lecture at nine o’clock, get the bus home for lunch, then go back down for the laboratories in the afternoon (for three hours from 2:00 to 5:00). There were laboratories about three days a week as they had them for physics, chemistry and zoology.

It was difficult to get through the intermediate year into medicine. In the first physics results, Wendy got 20%, which was shocking for her. “That sort of shattered me, that I needed to pick myself up. So I really tried hard. I got a C pass. Nearly a C plus. But people didn’t get As and Bs in our days, to get an A was almost unheard of, and B was pretty good.” About 600 students were applying, and Wendy did not know what grades the other students were getting. Only about 100 got in from Dunedin, although she thought it was harder for students who applied from Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch to get in. Just before Christmas, she received the letter with the news that she had been accepted, and she was ecstatic. “Oh, I was jubilant. Absolutely happy, because I really didn’t think I was going to get in. And I thought I’d have to – I was working out whether I should repeat or carry on with a science degree. Thinking my marks weren’t good enough.” She remembers running around the yard trying to find someone to tell the news to.

Medicine: no discrimination against women

Wendy was financially supported by her parents throughout medical school. In the first year after she left school, she decided that she needed some money to buy everything that she required for medical school, so she and a few friends planned to work as waitresses in Queenstown. However, her father refused to let her go, so found a job for her in Dunedin instead, working for the glassblower in the medical school, where she sorted out glassware, did stocktakes and learned to blow glass. Wendy returned to this great job most summers. She did not mind that she had not gone to Queenstown, and she does not think that any of her friends went either as all their fathers intervened. One summer she undertook the adventure of fruit picking in Nelson with some other girls.

Wendy’s favourite subjects in medical school were surgery and obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G), which she did well in. The professor of O&G in Dunedin was Laurie Wright. For the anatomy labs, the students were randomly sorted around the tables. In her second year, Doreen Bolton was on the same side of the table as her, and the other four students at their table were men. They all got along quite well. Her mother would always be able to smell her when she came home because she smelt of carbolic from the labs.

Wendy did not feel picked on for being a woman. “And if they were bullying, as they call it now, then the boys got it as much as we did, the girls did. Some of the lecturers said nasty things to the girls, but they also said horrible things to the boys as well. Especially if you had a motorbike and a crumpled white coat.” In fact, she thinks that she was “a little spoilt” because her family was fairly well-known.

Cricket: a year off from medicine to represent New Zealand overseas

Wendy grew up playing cricket. Her family had the largest flat backyard in the vicinity, so the boys from next door used to come over to play. “I used to bowl and bowl and bowl to them, and occasionally they’d let me have a bat.” When she got to high school, she joined the cricket team and found that the girls were much easier to bowl out than the boys she was used to playing with. Her talent secured her a spot on the school’s first XI. When she left school, her physical education teacher suggested that Wendy join the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) cricket club, which she did. Wendy devoted her summer holidays to playing cricket, as her friends from university had returned home and most of her school friends had left Dunedin, so she did not have friends to spend time with. Her skill secured her a place in the Otago team. At the Auckland tournament, she bowled the Auckland Captain and Vice-Captain. After her stellar performance, she made it into the New Zealand team, although two of her friends who had been keen to get into the team did not get in. “I remember being quite amazed that I was in. But very pleased, I thought I couldn’t possibly do it.”

The tournament required her to go overseas from March until October of 1966. When she asked the Dean of the Medical School (Edward Sayers) for permission to take the year off, she expected him to say no, but his comment was “Of course you must go. I let the men go to play their rugby, you must go and play your cricket.” So Wendy spent a year overseas between her fourth and fifth years. Her parents accompanied her to Wellington, where they were entertained at Parliament House. “I remember my father being a bit upset that I was the only one from Otago, they were all Cantabrian and Auckland girls. And whoever was making the speeches didn’t mention that there was an Otago person in the team.” The team left Wellington at the beginning of March and sailed through the Panama Canal to England, where they arrived on ANZAC day. “It was a long way.” Once they arrived, they had three weeks before the official tour started, so they practised at Crystal Palace. “And then, when the tour started, we had a bus and we went all around England playing games. Visited lots of schools, visited lots of sights, we were really looked after until we left in early September to come home on the Iberia through the Suez Canal. So it was six weeks, a boat trip home. Getting home sort of towards the end of October. So it really was a whole year out of medical school. So I grew up a lot, I’m sure.”

he team played three tests (at Scarborough, Edgbaston and the Oval). Wendy never played in the test teams, but she did enjoy keeping score for the first two tests. They also played county games, and visited schools, though they never played against school teams. Her best bowling figures were five for 37 against Middlesex.

After the farewell from Wellington, Wendy never saw her father again. While she was away, he was in a motor car which crashed at the bottom of a hill. “Then he went to hospital. He got over that, but he had been a heavy smoker and the Dunedin winter didn’t do him any good, so he went back into hospital and didn’t come out.” Wendy still remembers hearing the news while she was on her way home. She had just come back onto the boat after a day of sight-seeing in Gibraltar when she was told that the purser wanted to see her. He asked her if she was expecting bad news. Wendy’s reply was ‘maybe’, as she knew that her grandmother was ill. He told her bluntly that her father was dead and asked if she wanted to return to England (as he did not know that she was from New Zealand). Wendy was very upset, and this was exacerbated by the fact that she heard the news from someone she did not know. “I knew he’d had the accident, I knew he’d been in hospital. But I thought he’d got out and I thought everything was fine, so it was a big shock.”

“Well the boat was sailing through the Mediterranean, and then we got to Naples. And then in Naples Bruce [Hadden] rang up and told me what was going on because he’d been in the hospital with my father. So he was one of the last ones to see him alive. So we shouted – I shouted down the phone at the gangplank in Naples, I remember. It was not an easy connection, it wasn’t like picking up your cell phone today.” It took two or three days to sail through the Meditteranean, so her father was already buried by the time that she talked to Bruce (who she was seeing at the time). They sailed through the Suez Canal after going through the Meditteranean. This was just before the Six-Day War (5-10 June 1967) when the Suez Canal was closed, so they would have been some of the last people to go through it.

It was comforting to be able to see her family back home in New Zealand. Her father’s death had taken her mother completely by surprise. “He was sixty-three. He wasn’t old. And she was fifty-six. It did my brother hard because he was sixteen.”

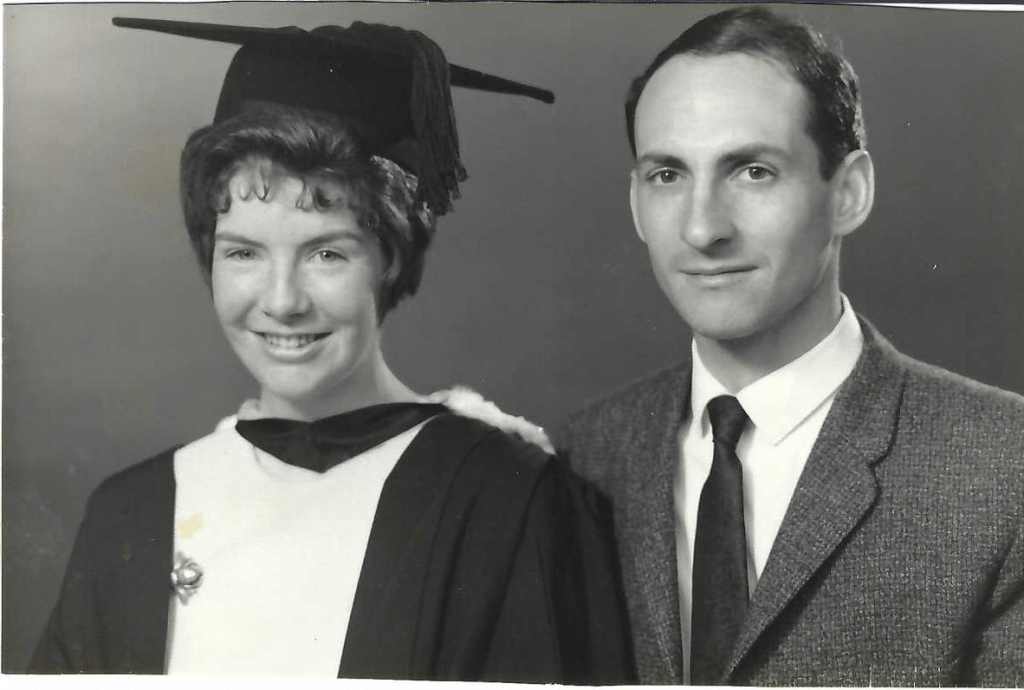

Continuing medical school: marrying Bruce

Wendy re-entered the fifth year of medicine in 1967. She had been writing to Bruce Hadden most of the time that she had been in England, and they got engaged upon her return. Since Wendy had taken a year out from her studies, he was a year ahead of her. They got married at the end of 1967, which was the end of the fifth year for Wendy, and just after Bruce’s graduation. She was the only woman in her year group who got married before graduation, although some of the men did.

Wendy went to Auckland for her sixth year (1968). “Because Dunedin was not terribly sympathetic to women house surgeons at that stage. Well, I don’t know whether it was rumour or not, but I think one of the doctors had said to my father that the other centres were more kindly to having women house surgeons that were married, than they were in Dunedin. That they were likely to send me off to Invercargill or Oamaru or Balclutha or somewhere, so I thought it was better to come to Auckland with Bruce.”

The students returned to Dunedin for their exams and graduated a week later (provided they passed). “The class I graduated with, I never felt was my class. Because how many of us would have been in Auckland doing sixth year, there would be about twenty or thirty, and I didn’t really get to know them very well, and then we all graduated together. In Dunedin.” Wendy also got a prize in Auckland for O&G, although her name was misspelt.

After graduation: eye-opener working at Mercy Hospital

Wendy got the job she wanted as one of two house surgeons at Mercy Hospital, which was called Mater Misericordiae at the time. She wanted this position because it meant that she would not have to move between Auckland and Middlemore hospitals when she was told to, which she would have if she had been working for Auckland Hospital. She spent her first two years after graduation there. The hospital, which was run by nuns, predominantly did surgery. “The ones in control of the wards were all nuns and there were a few junior nuns, and there was quite a large nursing staff, but the ones you really dealt with were the nuns. No, they were really good, I enjoyed working with them.” No registrars were working there, so Wendy was given more responsibility, and thus learned a lot. The house surgeons were responsible for the three public wards and the two geriatric and terminal care wards. There was also an obstetric unit. “If the GPs didn’t want to help with the caesarian sections then one of the two house surgeons would go and help.” Wendy would be on-call overnight every second week. It was not busy, as the nuns seldom called them, and sometimes they would call the consultants instead. Although none of the consultants were women, Rosemary Faull (a 1949 graduate) was “a jolly good anaesthetist” there.

Although Wendy is not Roman Catholic and is not particularly religious, working there was an eye-opener for her as she saw how deeply intertwined the patients’ faith and health were. They used to call the priest when patients were dying and this often helped the patients. Wendy remembers one patient who had systemic lupus with cardiac involvement who used to come in under Basil Quin, the physician. “And she’d have these heart attacks and she’d pass out, and the best way to get her around was to go in with the nun and say, I think we should call Father Brown, shouldn’t we Sister? So the moment you said that her eyes would open up and she’d come around. So I was never too sure if she really needed the medicine or not.” She later heard from her friend Ailsa Barker who was a registrar at Auckland Hospital that this particular woman had been admitted and had died. When Wendy asked if they had called the priest, Ailsa (who was a good Baptist), replied that they had not, but they had given her lots of drugs. “And I said, “Well perhaps if you called Father Brown she would have come around”. But who knows? She didn’t call Father Brown, and the poor lady didn’t come around, she died that night in Auckland Hospital where she couldn’t get into nursing.”

For the half-year while they were on the surgical run at Mercy, the house surgeons would work with Sir Brian Barratt-Boyes (the first person in New Zealand to perform an open-heart surgery), helping with his intensive care work, surgery and heart operations. “So we got to see all their notes and all their findings, we had open access to that. And I really enjoyed that, but I thought there’s no way I can be a heart surgeon, that would be beyond a married woman.” Sir Brian Barratt-Boyes was quite enthusiastic about Wendy doing intensive care work, but when she looked into it, she decided that there was no future in intensive care, since there was no specialty training at that stage. Wendy’s next idea was that she would apply to be a radiology registrar, after seeing Dr Peter Brant, who did the x-rays and catheter studies, and realising that radiologists had better hours and no night-shifts. She did apply, but she does not know whether or not she got accepted because she became pregnant, and decided to pull out. “I was pregnant, and about the time the baby was born I would have had exams, so I opted out that year. I thought long and hard about it and decided I’d just defer things.”

Therefore, instead of going straight into radiology, Wendy did some GP locums with David Dove on Remuera Road. At the time, GPs were allowed to deliver two babies at National Women’s Hospital each month, so Wendy did this. She spent three years working as a GP, and she had quite a large female practice.

“Well the one I do remember was one… I was doing a locum for David Dove and he had some prominent Remuera ladies, and one day I had a brow and a breech, so I diagnosed the brow, we got an x-ray and it was a brow and Pat Dunn helped, we sectioned her. And then as I was leaving the hospital they said the other lady had come in, so I examined her and thought, oh well I’ve got time to go home for dinner and come back again. And they called me to say that the second lady was nearly ready, so I rushed in. And of course it was a breech, wasn’t it? I hadn’t picked that up earlier. So I remember ringing Mr. Dunn and saying, “I’m here, it’s midnight and I’ve got a breech.” And he was there within two shots, he had a clean white shirt on, looked like he’d just had a shower and was ready to go. And so we delivered the breech, well that was alright, I was sitting at Auckland Grammar interviews for the new parents, and sitting beside me was the mother of the breech. And the breech baby was a good friend of my youngest son, they were in the same class together. So the breech turned out alright.”

Further training: a letter inviting her to be a radiology registrar

Once Bruce had passed his fellowship exams, they moved to America for two years. The couple had two children by then (Andrew and Peter). Bruce worked at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, while Wendy dedicated her time to being a mother. After two years there, the couple wanted to come home, but Bruce did not have a job arranged in New Zealand. Out of nowhere, Wendy received a letter from Bryan Trenwith (who was the director of radiology at the time) saying that they would be happy to have a woman radiology registrar the next year. Wendy is still not quite sure how this eventuated, but she thinks that Cynthia Rutherford (who was one of the house surgeons she worked with at Mercy Hospital) had told him that Wendy was coming back and had been going to do radiology.

Wendy accepted the offer from Bryan Trenwith, so the family returned to Auckland and she started as a radiology registrar in mid-December. Bruce did not have a job at this stage, but he knew that they were planning to employ a senior lecturer in ophthalmology; he was thinking that he might be offered that or a tutor specialist job. Bruce did not end up getting this position, but he joined some others at a private practice and then got a consultant job.

After spending a couple of years as a full-time mother, Wendy found it difficult adjusting to full-time work as there was no late-night or weekend shopping. She pushed hard for the College of Radiologists to allow her to train part-time, and after about six months, they allowed her to work seven tenths. This training position spanned all Auckland Hospitals. When Wendy returned to National Women’s, she saw Dennis Bonham, who enquired as to why she was not doing O&G. He was the postgraduate professor of O&G in Auckland (who she thought was “quite a good teacher”). As Wendy had done lots of women’s health, and she liked doing hysterosalpingograms, she ended up in women’s health radiology.

Wendy did a locum for John Stewart for three months, while he was overseas looking at ultrasound scanners; this gave her the opportunity to go to National Women’s. “And that was my first introduction to doing a lot of the obstetric work. And enjoying it, and getting quite facile with reading the x-rays, the baby’s maturities. You could put them up and you could say whether it was thirty-six weeks or thirty-eight weeks.” National Women’s had a diasonograph at the time, but this was heavy and difficult to use, so John Stewart was looking at the more modern ultrasound scanners. Wendy enjoyed seeing the advent of ultrasound throughout the time that she worked.

When covering for John Stewart, Wendy did some x-rays to guide Bill Liley’s fetal transfusions. The research was around preventing Rh incompatibility and subsequent haemolytic disease of the newborn. There was a sense that they were making history. And they were. Wendy did some of the transfusions with Florence Fraser (a 1963 medical graduate). “And we used to cheat, we used to go and do the ultrasound and see where the baby was and by the time we had the lady on the table in the screening room, cheated with the ultrasound where the baby was lying and then told Bill after he’d palpated it, where it was. So he didn’t approve of us using the ultrasound. He thought you could palpate it better than you could the ultrasound.”

Most doctors went overseas once they had finished their specialist training. It would not have been easy for Wendy to do this, as Bruce had already started working as a consultant. Dennis Bonham helped her to get a consultant job in radiology in New Zealand instead. “I know that for a fact, that he was one of the ones at the meeting that stood up for me. And then he supported me coming back to National Women’s.”

There were quite a lot of female radiologists (including Anne Hewitt and Alison Sommerville) because the position provided good hours. “You know, you could finish your screening session and that was it for the day. You didn’t go home and get rung up about something.”

After Wendy’s sons had grown up, she increased her work-load, working half-time at National Women’s Hospital and half-time at Auckland Radiology. She also did charity work with Nurture, which she enjoyed. “That was quite different, having jewellery parties.”

Retirement at the age of 70

Wendy did not feel ready to retire until she was 70 years old. She had told National Women’s Hospital that she would work until she was 70, so she stuck with that, and her last day working was on her 70th birthday. They wanted her to teach, but she decided that it was time to cut her ties. “Because if you didn’t do a lot of radiology, you lost your skills. And I didn’t want to be seen to be that old woman who didn’t know what she was doing.” She had retired from Auckland Radiology a year earlier because she felt that there were new people coming through who would have better ideas than her.

Greatest career achievements and advice to women in medicine

“Well if you’re a woman in medicine, you need a jolly good supportive husband and family. And I had that.” Wendy also had an assistant, Auntie Hel (who was not actually an aunt), who looked after the boys from when Andy was three until he was 17. Wendy would come home to find the ironing done and the meal cooked; Auntie Hel never left until either Bruce or Wendy was home. “So without her, I couldn’t have managed. So you need support. You can’t do it alone.”

Wendy believes that the greatest achievement of her career was helping patients with infertility who could not have children, which she did using lipiodol, hysterosalpingograms and ultrasound.