This biography is primarily based on information from ‘A Dame We Knew: A tribute to Dame Cecily Pickerill’ by Beryl Harris and Harvey Brown’s ‘Pickerill : Pioneer in Plastic Surgery, Dental Education, and Dental Research’. Approval for this biography was given by Cecily’s niece, Fay Hope. We are grateful to Beryl, Harvey, and Fay for their support of this project.

1925 Graduate

Contents

Early life and family: attending a school for “Christian gentlewomen”

Cecily was born on February 9th 1903 at the Ruanui Maternity Hospital in Taihape, to Margaret Ann Hunter and Percy Wise Clarkson, who were immigrants from England. She had two older brothers (Stanley and Ivan) and two younger sisters (Madeline and Esme). Percy was the first Anglican Vicar in Taihape and was known as ‘The Reverend’, so the children were brought up in a devout Anglican household. The Church that they attended was ‘St Margaret’s’, and the children believed that it was named after their mother. Cecily remained very close to her family throughout her life and she loved them dearly. Her father became unwell in the war, but he recovered physically upon returning to New Zealand (although his personality did change).

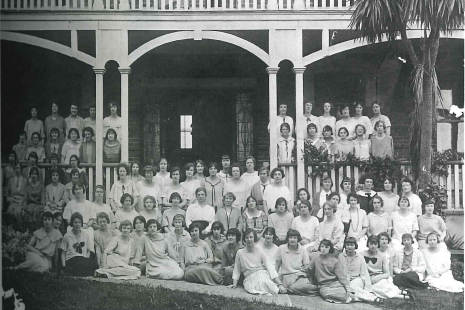

Cecily and her siblings attended Taihape School until they moved to Auckland in 1914. From then on, Cecily boarded at Diocesan School (which she and her sisters coined ‘Dying Sausages’). This was a school for “Christian gentlewomen”; its aim was to educate girls to become ladies. Cecily and her sisters were able to attend this expensive school because they were granted a scholarship for the children of clergy. When she was at school, Cecily was recognised as a girl who was expected to carry herself well, to be of a high moral standard, and thus to be an example to her fellow students. This was shown by the fact that she was allowed to wear a cherry-red girdle, rather than the navy girdle which her classmates wore.

Cecily studied hard throughout her school years, as she already had a desire to become a doctor. There was no premedical year or interview; entry was based purely on one’s results from their school exams. To get into medicine, students had to pass exams for English, French and Latin, but Cecily’s school only allowed her to study two languages. She did not give up, but instead woke early each morning to teach herself French. She was successful in the exams and made it into medical school, which she began in 1920.

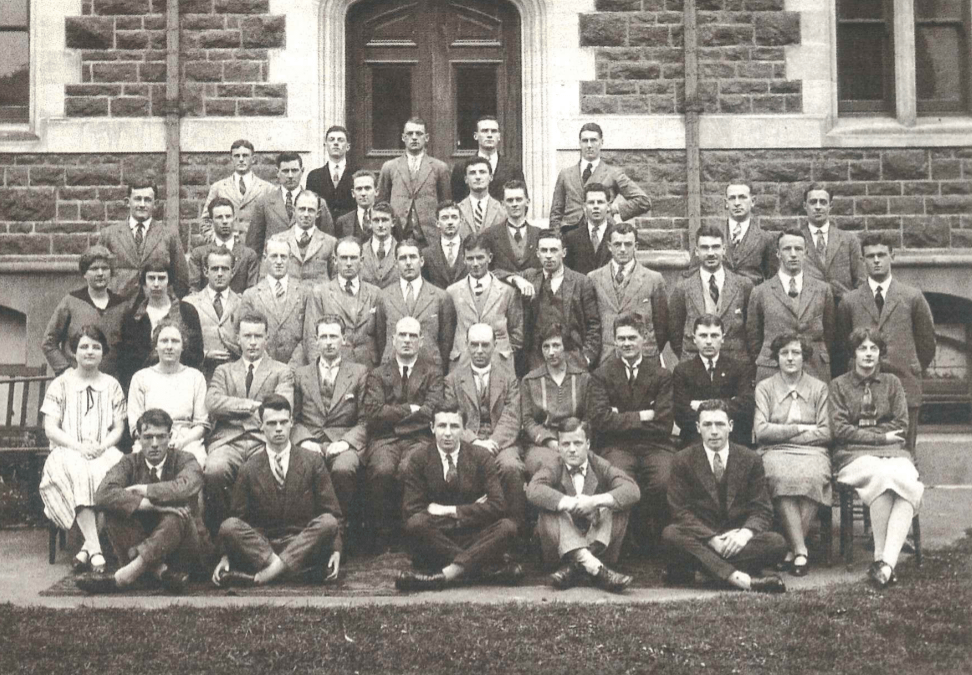

Medical school: ostracisation of female students

Cecily was one of only three students to be granted the university scholarship for children of the clergy; without this, her family would not have had the financial security to provide her with further education. This covered her university fees, but not her board at St Margaret’s College, which her parents paid for. In her first year (1921), the weekly cost of boarding was 14 shillings and eightpence; by 1924, this had increased to 16 shillings and sixpence. Extras (like the use of the iron and telephone) had to be paid for on top of this.

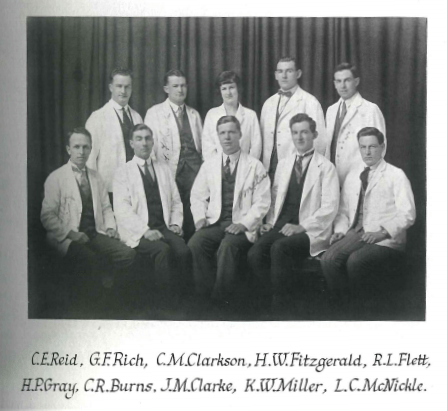

Medical school was a harsh contrast with Cecily’s sheltered childhood. After just one anatomy class, in which the students had to dissect a cadaver, she was ready to go home. Cecily struggled with – and even had nightmares about – chemistry and physics, which she had not studied at school, and she once had to resit an organic chemistry paper. Throughout medical school, she predominantly worked as the only woman with a group of eight men. Even though she was outnumbered and she faced many challenges, she did not give up. She graduated in 1925 when she was only 22 years old.

It was not easy for women in medicine at this time. They had to endure many insults and were excluded from the rest of the medical school, being forced to sit at the front of the lecture theatres and not being allowed to attend the medical school dinners. They were not referred to as ‘female doctors’, but were instead called ‘lady medicals’ – though the men were called ‘male doctors’.

One teacher at the time was Professor Henry Percy Pickerill (whom the students affectionately called ‘Professor Pick’). He had previously worked at Sidcup Hospital in Kent, where plastic surgery in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries began. He was New Zealand’s first plastic surgeon and was the first Director of the Dunedin Dental School. He had recently returned from operating on World War One victims, where he earned a reputation for his skilful work. The students felt privileged to have such a prestigious and experienced teacher lecturing them about conditions of the mouth, stomatology and dentistry.

After graduation: family troubles

Beryl Harris remembers Cecily’s story of how she ended up as a house surgeon for Professor Pickerill in 1926. “Well, when our graduation results came out and the positions available went up on the board, the boys all clustered about and one passed me a card saying, ‘here’s one for you Cecily, you like sewing’! And, so it happened. I applied and was appointed as house surgeon to Professor H.P. Pickerill.” She loved the work that she did with him.

While Cecily was at medical school, her parents and sisters had moved to America. Cecily had decided that she would join them once she finished her first year of registrar training, so she travelled to California in February of 1927. She took with her three references: from Dr R. Faulkner (the Medical Superintendent), Professor Charles Hercus (the Dean of the Medical Faculty) and Professor H.P. Pickerill, who wrote that she was the “Best house surgeon I have had for some years.” With these references, Cecily secured a psychiatric residency job, but she soon discovered that it was not to her liking. She also found that the family dynamics had altered drastically. Her father had changed in the war. Though he had once been a devout Anglican, he was now experiencing many changes in faith and he had filed for a divorce (though this was called off in May, 1929). Naturally, this was very upsetting for Cecily, so she decided to move to Sydney and return to the work that she enjoyed.

Dr Henry Pickerill was also in Sydney. He had moved there because Dunedin Hospital had refused to increase his salary whilst also barring him from doing any private practice on the side. In Sydney, Cecily worked as his student, understudy and assistant. “She in effect became Pickerill’s apprentice, learning all his surgical skills as his assistant, and later his associate” (Pickerill, p.212). They worked part-time at St Luke’s Hospital and Royal North Shore Hospital, as there was no full-time work available. Henry had also set up consulting rooms at 193 Macquarie Street, which is where he was when he announced his arrival to the medical and dental professions. In 1929, the pair bought and developed a property at Narabeen, which they named Caradoc (Pickerill, p.213).

At this point, Henry was married to Mabel and he had four children. It is not known why, but the original plan was for Henry to move to Sydney and establish himself in practice. Once established, his family would follow. This was not to be the case. In 1931, Henry petitioned for divorce “on the grounds of having been wilfully deserted for three years and upwards” (Pickerill, p.212). The official divorce was granted on 20 November 1934. Nearly one month later, on 17 December 1934, Henry and Cecily were married at Enfield, New South Wales in a small, private ceremony. Cecily was 31 and Henry Pickerill was 55.

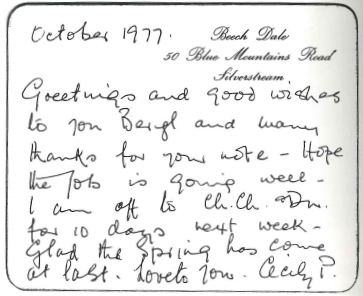

Australia was in recession (beginning with the Wall Street crash in 1929), so there was not much demand for cosmetic surgery. Though Henry had moved to Sydney in 1927, it took until 1934 for him to obtain a formal position as the honorary plastic surgeon at the Royal North Shore Hospital – the first position of its kind in Australasia (Pickerill, p.214). However, the conditions in Australia were not sustainable, so the couple moved back to New Zealand once they were married. Henry continued to hold the position at Royal North Shore until 1936, and he had spent the last two years commuting between Sydney and Wellington. In 1935, they bought three acres of farmland in Silverstream, and with a cash grant of £80 from the government (which the government was using to encourage people to build their own homes), they built a cottage called ‘Beechdale’, which they moved into in 1936, around the same time that Cecily gave birth to their daughter, Mary Margaret Ann (who later became a nurse) (Pickerill, p.238). They both loved this property and enjoyed tending to the garden. Cecily particularly loved the rhododendrons that she grew. The couple would sometimes open up their beautiful garden to the public for charity. The garden was home to two beloved pūtangitangi (Paradise shelducks), called George and Mildred. It was an upsetting time for Cecily when Mildred died and George wandered away.

Both Cecily and Henry initially worked at Wellington Hospital. They operated on patients from the Second World War; Henry as a plastic surgeon and Cecily as an anaesthetist. Henry was already renowned for his work during World War I, and he taught Cecily as they worked, even letting her do some operations. In these early days, it was not common for a woman to be a surgeon, so they would only tell the patient afterwards that a woman had done the operation. Throughout her life, Cecily maintained that everything she knew, she learned from her husband.

In 1938, the couple established specialist plastic surgeon consulting rooms in Kelvin Chambers on The Terrace and conducted the operations at Lewisham Hospital in Newtown (Pickerill, p.215). Between 1941 and 1951, they also operated on a small number of patients at the Home of Compassion, Island Bay, primarily for cleft lips and palates.

From 1940 until 1945, Cecily was the Assistant Plastic Surgeon at Wellington Hospital. She was appointed as acting senior plastic surgeon in 1945 with Henry Pickerill as her supervisor. However, when she asked to make this position permanent, she was turned down, probably because she did not have any postgraduate training. As Beryl Harris put it: “She faced discrimination from the start. She was criticised for not being qualified, but in fact, there were no qualifications available for women until 1947 and she started in the field in 1935. In fact, she had the best apprenticeship possible, working alongside Henry Pickerill for 25 years.” Cecily was made a Member of the British Association of Plastic Surgeons (MBAPS) in 1949. Specific postgraduate plastic surgery training was beginning in New Zealand in the 1950s, but Cecily never felt the need to do this; she believed that she knew everything she needed to know as she had been taught well by her husband.

Bassam: ‘The Home Barn’

In 1939, the couple established Bassam, which translates to ‘The Home Barn’ in old English. It began as a hostel for mothers and babies who were having operations at one of the Wellington hospitals (Wellington Hospital, Calvary or Lewisham (now Wakefield)). In 1942, it became a plastic surgery clinic for babies and young children with congenital defects, such as a cleft palate or a harelip. Bassam was recognised as the National Centre for Infants’ Reconstructive Surgery until the service at Hutt Hospital started. People came from far and wide to have their operation done at Bassam and the Pickerills generously travelled to other towns for follow-up appointments. There were eight rooms at Bassam, seven inside and one outside. The couple operated four days a week. After 1945, the couple stopped their public work, as they were too busy at Bassam.

Even though Bassam was privately run, mothers did not have to pay (although they were given the opportunity to provide a donation). They were supported by the Crippled Children’s Society (CCS) (now known as CCS disability action), who paid for accommodation and transport for the mothers and babies. Bassam only received the standard medical schedule fee of £9 per surgery – the same as the hospitals received. In 1951, Cecily became the medical officer to CCS. She held this role until she retired, and from then on she was the Honorary Vice President of the CCS. Bassam’s only real source of income was the private (paid) cosmetic surgery work which the Pickerills did each Wednesday. The couple paid all their workers, who included three female medical graduates: Dr Jessie Burnett (the anaesthetist), Dr Dora Young and then Dr Claudia Shand (Cecily’s relief person).

Cecily proved that her method of ‘insulation, not isolation’ could prevent the spread of infection. Each mother and her baby had a room to themselves, which was cleaned before they came in. Contact between the baby and anyone other than its mother was minimised as much as possible. Even family members could not come in; they had to communicate through the window! Not only did this reduce the anxiety for the babies, it also stopped the spread of infection, as babies carried the same immunity as their mothers. “In those pre-penicillin days … there was always the danger in big hospitals of cross-infections. Infections could make a complete failure of a surgeon’s work”. One of the benefits of preventing infection was that it stopped scarring. This early rooming-in style of caring was ahead of the times; rooming-in was not introduced in New Zealand hospitals until the 1950s. The favourite saying at Bassam was: ‘You look after your baby. We will look after you.” Their method was successful as well; after only eight years they showed a 0.3% mortality rate post-operative, whereas overseas the rate was between 1.4-3.4% (Pickerill, p.218)

Cecily and Henry explained their reasoning in an article in the British Medical Journal. “We felt that there was no reason why any cleft-palate, hare-lip, or hypospadias operation for infants should ever fail, provided that the right conditions could be obtained for their treatment. What we felt was necessary was some place where mothers could stay with their babies in peace, cleanliness, and happiness, and with reasonable facilities for treatment, and where extraneous sources of cross-infection could be rigidly controlled.”

To prepare for each operation, Cecily would be sent a photo of the baby to determine its weight, whether or not it was thriving, and the repair operation which was required. The baby needed to be thriving before the operation could be done. The mothers would spoon-feed them to help them gain weight, and the operation was normally done at 10-12 weeks. After the operation, Cecily would show the mother how to massage the lip to prevent scarring. Most mothers were amazed by the change the surgery produced. Children usually required speech therapy as they grew up, to ensure that they did not have a lisp or other speaking difficulty.

Bassam was described as being friendly; more like a big home than a hospital. Many of those whom Cecily operated on remember her fondly and are incredibly grateful for the positive impact that she had on their lives. She was ahead of her time and had a higher success rate in plastic surgery than the public hospitals did. Those who were treated by her also claim that her work was at a higher standard than that of other plastic surgeons at the time. It is not hard to see that she genuinely cared about her patients and her work. She loved it when her patients called or visited her when they had grown up. She always remembered them. “It was a particular joy to her to know that many of these children could one day attend school without being teased and tormented by other pupils.” – Beryl Harris.

Cecily was the first plastic surgeon in New Zealand to specialise in children (Henry specialised in adults). Despite her success, it was not always easy. As she worked in the private sector, she was isolated from her peers and did not feel as though she was completely accepted by others in the profession.

Cecily tried to tell others about how successful it was for mothers to nurse their babies. She and her husband gave many speeches, not only about their success, but also teaching the importance of speech therapy and follow up operations as the children grew up. They also wrote articles for medical journals. In 1954, Cecily and her husband co-authored a book, “Speech Training for Cleft Palate Patients”.

The couple also started the early plastics service at Middlemore Hospital. They had been offered full-time positions there, which they declined, but they took turns going in to operate once a month, from 1947 until 1950. It was a long journey which involved catching the express train from Wellington to Auckland on Friday night, doing a surgery clinic on Saturday, then returning to Wellington on Sunday. During the rest of the time, the house surgeon, Dr William Manchester, would manage the clinic and look after the patients.

Cecily’s father died in 1942. In 1945, Henry Pickerill’s health began to fail. This is thought to have been an effect of the ether that he used as an anaesthetic for his operations during the war. His health problems included deafness and severe angina. As his health deteriorated, he became increasingly dependent on Cecily as his carer and interpreter. Once he became too unwell to work, Cecily did all the surgeries herself. He died in their Beechdale cottage in 1956, at the age of 77. Cecily developed Bell’s palsy soon after his death, so from then on, she had to use a magnifying glass on one eye for operations. She continued working at the Bassam for ten years after her husband passed away.

The Bassam closed in 1969 and later reopened under Bloomfield Hospital.

Well-deserved recognition

In 1958, Dr Cecily was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), and in 1977, she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) for services to medicine, especially in the field of plastic surgery. She was New Zealand’s first medical dame.

The citation was: “Dr Pickerill, who qualified in Dunedin in 1926, has for many years specialised in cases of cleft palate, harelip and other congenital defects, and burns amongst children. She has restored full life to many hundreds of children. Her experience in this field, developed with her late husband, Dr H P Pickerill, CBE, has been recognised throughout the world. They founded a private hospital in Lower Hutt, to facilitate this type of surgery along with mother nursing to avoid cross infection by enhancing the mother and infant immunity.”

Retirement: more time in the garden

“I have been privileged to do some of the most rewarding work in the world.”

– Dame Cecily when she retired.

When Cecily retired in 1968, no-one wanted to take over the running of Bassam. So, Bassam instead became ‘Bloomfield Hospital’ for the elderly. Cecily chose to retire at this stage because she felt it was better to stop when she was still enjoying her work, rather than wait until she was not. She was also aware that some of the equipment that they used at Bassam (such as their anaesthetics) were very out of date.

Cecily still had patients coming to her when she was preparing to retire. She started phasing out operations by working as a visiting surgeon at Palmerston North Hospital, and she referred her patients to William Manchester in Christchurch (who had been her house surgeon in Middlemore years earlier). She is aware that once she left, some of her patients did not return for their final appointments. This upset her, as she knew that there was more that could have been done for them.

Once she had retired, Cecily continued to fill up her days. She joined the Rhododendron Society of New Zealand and the Camellia Society of New Zealand and was also active in the St John’s Church. She loved being able to spend her time in the garden. “I am now as devoted to horticulture as I once was to mending Kids.” A friend developed a red rhododendron that he named ‘Rhododendron Dame Cecily Pickerill’ as Cecily loved red flowers. Cecily was also involved with the Red Cross and was a patron in her later years. When she died, she left a legacy to the Upper Hutt branch, which they have since used to provide a lecture given by a distinguished Red Cross member once every two years.

Mrs Weir had been the housekeeper for 26 years, and she kept Cecily company during her retirement. As Cecily grew older, she started to lose her eyesight and her hearing. Mrs Weir drove her around and her friends wrote out cheques for her. During her retirement, Cecily made one last trip to the United States to visit her family there.

Cecily’s failing eyesight led her to trip on a step in the shed one day. The result of the fall was a broken arm and a slice off one leg. Cecily was admitted to Hutt Hospital to have a skin graft on the leg, but in 1986, when she had been there for a month, she had a stroke. She was moved to Bloomfield Hospital (the old Bassam) for the last two years of her life. After the stroke, she was paralysed and struggled to speak, but she asked to share a room so that she would not be alone. Cecily had a characteristic chuckle that she kept until the end. At the age of 85, on July 21st 1988, Cecily died in the building where she had dedicated so many years to helping children. She left behind a daughter, Margaret Frazer, and two grandsons (Rob and Richard). Her legacy remains in the many lives that she touched.

Bibliography

- Harris, B. (2014). A Dame We Knew: A tribute to Dame Cecily Pickerill. www.diypublishing.co.nz

- Pickerill, Cecily M A W. (2016). Capital & Coast District Health Board. https://www.ccdhb.org.nz/about-us/history/wellington-hospital-smo-archive/appointments-made/1921-1940-honorary-staff/plastic-surgery/pickerill-cecily-m-a-w/

- R. Harvey Brown. ‘Pickerill, Cecily Mary Wise’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4p12/pickerill-cecily-mary-wise (accessed 22 January 2021)

- R. Harvey Brown. Pickerill : Pioneer in Plastic Surgery, Dental Education, and Dental Research. Dunedin, N.Z.: Otago University Press. 2007.

- Wellington Region Heritage Promotion Council. (January/February 2016). Nurse honours her heroine in new book. Heritage Today, 7(14), 5. https://www.wrhpc.org.nz/library/201601-02_heritage_today.pdf

- Brown E, Klaassen MF. War, facial surgery and itinerant Kiwis: the New Zealand plastic surgery story. Aust J Plast Surg. 2018;1(1): 51–63. https://doi.org/10.34239/ajops. V1i1.32

- Pickerill, H. P., & Pickerill, C. M. (1945). Elimination of cross-infection. British Medical Journal, 1(4387), 159.