This biography was written by Deborah Jowitt, Anne’s daughter, in 2021 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project.

1951 Graduate

Contents

Early Years in England

Anne Priscilla McKinnon (nee Pearson and Jarvis) was born at her parents’ home, 3 Burton Street, Loughborough, Leicestershire, England, on 24 January 1924. Anne was the third of three daughters. All the girls had nicknames: Eleanor was ‘Bysshe’, Rosemary was ‘Ribby’, and Anne was ‘Poggerel’ or simply ‘Pog’. Their younger brother Howard, named for an uncle who had died in the Great War, completed the family.

Anne’s father, William Pearson, an electrical engineer, was general manager of Loughborough’s Brush Electrical Engineering Company. Her mother, Norah Pearson (nee Moss), was trained in home science. She was a descendant of William Moss, who established a successful family construction business in Loughborough in 1820, which continued to undertake major building contracts in the Midlands and Liverpool into the mid-twentieth century.

William was raised as a Wesleyan and later became a humanist. Norah’s family were Baptists, but she later converted to Catholicism. To reconcile their differences, they brought their children up as Anglicans. Norah was regarded as ‘quite a girl’ in the 1920s, with an Eton crop, a ‘risque’ sense of humour, and a motorbike. She had a fine singing voice, and her enjoyment of music hall favourites contrasted with her husband’s more refined tastes in music and literature. However, she was well-read, spoke good French, and was determined her daughters would have an excellent education.

Throughout her childhood, Anne’s world revolved around her home and her extended family. She attended the local primary school where the headmistress was a friend of her mother’s. Norah could be strict but was a very good cook and had a strong sense of social duty; Anne often went with her on visits to the sick and the bereaved. They were also encouraged to think and discuss a wide range of topics: William made sure he had time with the children in the evenings, discussing history, geography, architecture, and general matters.

The family’s comfortable existence was shattered in the mid-1930s when William resigned from his position at the Brush rather than go along with shady deals that he was being pressured into from within the company. As a result, the large family home was sold, and a modest terraced house was purchased to make it possible to keep the children at school and university. Despite their strained finances, her parents were keen on giving Anne the best chance of achieving academic success.

When she was ten, Anne attended Herbert Strutt School in Belper, Derbyshire, as a weekly boarder with the Arnold family. The school was renowned for its education and for getting scholarships to Oxford and Cambridge. Mrs Arnold, who had studied at Oxford, gave Anne additional tutoring, which she found helpful in gaining competency in maths.

Anne suffered badly from hayfever as a child; an early memory was of being taken to a medical specialist who cauterised her nasal passages with cocaine to treat epistaxis secondary to severe hay fever. In 1936, she won a scholarship to Talbot Health Girls High School in Bournemouth, Dorset, where she spent four happy years as a boarder; the sea air alleviated her hayfever, and she enjoyed study and sports. Talbot Health was a progressive school that provided an all-round education for girls, and its focus on quickly condensing written information would prove very useful when Anne later studied medicine. Her final school report noted that ‘her homework might sometimes go further, as she works quickly and ably in gathering her material together’, but that ‘her future promises well’.

The War Years: Study, Enlistment, and Marrying Steve

World War II broke out in September 1939. Six months later, Anne left Talbot Health to study art at Loughborough College. She planned to go to university once the war ended, and this expectation was encouraged by her parents. But when she expressed a desire to study architecture, they advised her against it because they felt it would be much more difficult for a woman to make a living as an architect than as a doctor.

Medicine was already an established career path in the family: Anne’s oldest sister Eleanor had completed her medical degree at Liverpool University in late 1939. In addition, their great uncle, Bertram Wilmore Moss, had qualified in medicine in the mid-1890s. He served in the British Army during the Boer War and then travelled widely as a personal physician to a well-to-do family before returning to practice as a consulting surgeon in Leicestershire.

Eleanor and her husband John Hamilton, an obstetrician, remained in Liverpool throughout the war despite the heavy bombing of the city because of John’s essential role. Eleanor became a lecturer in histology after graduating, but with rapid advances in her field and a growing family, decided against specialising further.

Anne was keen to contribute to the war effort, and in July 1941, enlisted with the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). In August 1941, she was transferred from Leicester Reserve to RAF Portreath, Cornwall, as PA to Wing Leader Minden Blake, the New Zealand flying ace. Anne’s abilities in French and German were noted by the RAF and may have played a part in her transfer to Portreath. At the time, Britain anticipated a German invasion by sea, and Anne recalled the beach at Portreath being off-limits with rolls of barbed wire in the surf.

Anne was only 17 when she met her future husband, Flying Control Officer Walter (Steve) James Jarvis, who was based at RAF Predannack, a satellite airfield of Portreath. Steve had brought another New Zealander, Hector Bolitho, the editor of the Royal Air Force Journal, to Portreath to interview Blake. He was unavailable, but Anne and Steve felt an immediate attraction. Steve was very tall, handsome, and well-built – he had been a surf lifesaving and swimming champion in New Zealand in the 1930s. The relationship was a classic wartime romance. They married in December 1942. Anne was not quite 19 years old.

The couple were separated for long periods during the war. In 1943 Anne was recommended for a Commission in the Code & Cypher Branch. In February 1945, after more than a year at RAF Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides, where she was stationed with No.304 Polish Bomber Squadron, she resigned from the WAAF as an Assistant Section Officer. Steve transferred to the NZRAF around this time and returned to New Zealand with the intention of enrolling at Otago University for medical preliminaries. Anne followed later the same year. They made a mutual decision to study medicine together, and in October 1945, Anne was officially ‘exempted from passing in Science with necessary to complete Medical Preliminary.’

Otago Medical School Years

The class of 1946 had six women students. It included a range of ages and experience, from school leavers to older military returnees. Married students were the exception; Anne and Steve were among the six per cent of Otago University students surveyed in 1946 who were married, and among the four per cent living in a flat, rather than at home, in ‘digs’ or boarding.[i] Their first flat was at 39 Royal Terrace; they then moved to 23 Cairnhill Street, Maori Hill, where they stayed for the remainder of the medical course. Flats were hard to come by, and in 1948 Anne’s brother-in-law Sydney, an engineering student, and his wife Priscilla, a science student, moved in and flatted with them for two years.

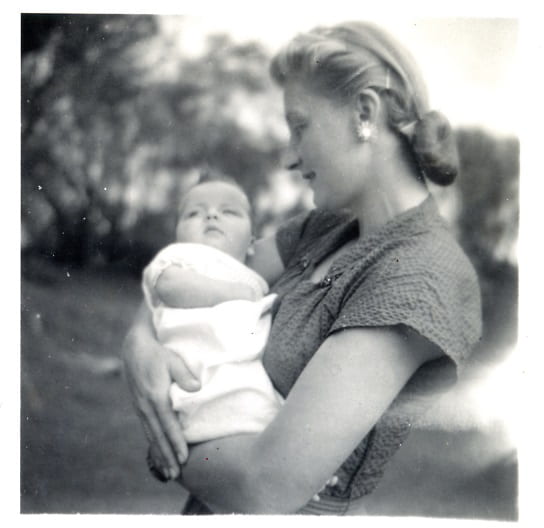

They funded their studies through their service bursaries, supplemented by work during university breaks. During their first year, Anne became pregnant with their first child, Felicity, who was born in February 1947. So that Anne could continue studying, Steve’s family took Felicity to live with them in Auckland. When Anne became pregnant again 15 months later with their second child Stephen, Anne’s mother and father decided to emigrate from England to look after both children while she and Steve completed their degrees. William had been a member of the Fabian Society and was enthusiastic about leaving England for what he idealistically described as a ‘socialist paradise’ in New Zealand. They settled in Dunedin and looked after both children during the week, with Anne and Steve caring for them during the weekend.

Anne recalled their time at Medical School as a happy one. She enjoyed study and did well. The primary challenges of the medical course were getting up to speed with chemistry and physics and being a mother to two children. Anne was surprised to discover she enjoyed babies and motherhood – she hadn’t anticipated having such strong maternal feelings. Motherhood also had other benefits – she was exempted from practical obstetrics as it was felt she had adequate personal experience.

Steve was a lifelong smoker, but Anne never took up the habit. She was one of the few students in the class who didn’t smoke and remembered the smell of the dissecting room as a powerful mix of formaldehyde and cigarettes! She was a very moderate social drinker. Her father was teetotal, and alcohol had not played a big part in her upbringing. There was little time for socialising, but both she and Steve were enthusiastic participants of the annual capping parade. Anne was also involved in student politics: from 1950-51 she was the ‘Ladies’ Representative’ on the Otago University Medical Students’ Association Executive.

Early Career in General Practice

Anne and Steve qualified in late 1951. Anne’s parents returned to England, with her father lamenting the fact that workers in New Zealand were much more interested in ‘rugby, racing and beer’ than politics. Steve took a position as a house surgeon at Whangarei Base Hospital, while Anne worked as a locum in a GP practice at Hikurangi, 17 km north of Whangarei. On her first morning, she was called to the Waro limestone quarry, where there had been a serious accident. She arrived to find the patient deceased. It was a memorable start to a 40-year medical career.

In late 1952 Anne and Steve bought a general practice in Kaitaia, and a spacious house with a large garden at 1 Dominion Road, just around the corner from the hospital. Steve took a central role in the surgery, including the obstetric side of the practice, while Anne worked around the demands of family life. She had their third child, Deborah, in January 1953. She was determined to enjoy time with this baby and breastfed her for six months. Managing work alongside motherhood was to become the dominant theme in her medical life.

In January 1955, Anne gave birth to their fourth child Michael. He was thriving until Anne took Michael with her as a boarder baby when she was admitted to hospital in June 1955 with a severe infection. The ‘H’ or ‘Hospital Bug’, a penicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus causing worldwide epidemics of hospital infection, was just beginning to make itself known in New Zealand. On their return home, Michael developed low-grade temperatures and was reluctant to feed. He would appear to recover, then worsen, eventually taking fluids only by eyedropper. In desperation, Anne consulted Dr Jack Dilworth-Matthews, a paediatrician at National Women’s Hospital, who promptly diagnosed ‘systemic antibiotic-resistant Staph infection’ and prescribed erythromycin, at the time the most effective treatment for resistant infections.

The strain of her illness and caring for Michael had an impact on Anne’s health. At the same time, Steve found the workload of a semi-rural GP challenging with a growing family. They also wanted more options for the children’s education. Anne took a six-month break in England with their three older children, while Michael stayed in New Zealand with Steve’s parents. The time away gave her an opportunity to rest and reconnect with her extended family, and she returned ready to pick up part-time work again.

The couple left Kaitaia and bought a GP practice in Howick. Although people frequently commented that it was ‘much too far out’ of Auckland, they liked the proximity to the sea. In 1958 Anne worked part-time in the surgery and took a part-time position with the School Medical Service, going from school to school in her intrepid Morris Seven. She later recalled how much she loved ‘getting away and driving to the different parts of Auckland’, especially West Auckland communities like Piha and Muriwai, where the bush met the sea.

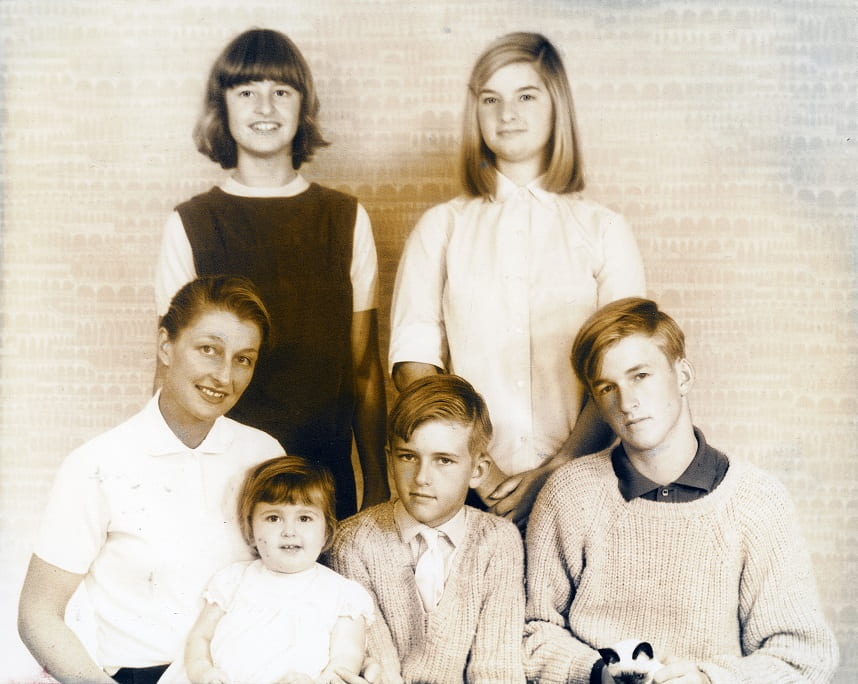

In 1959, Anne and Steve decided to move closer to ‘town’ for schooling and a city practice in the Lister Buildings, Victoria Street East, Auckland. They primarily saw office workers but also cared for the Chinese community centred around Greys Avenue. In 1961, they bought a prime section above Howick beach, where they intended to build and live in the future. However, their marriage did not survive the move to Howick in mid-1963. At the time, Anne was pregnant with their fifth child, Elizabeth, who was born in February 1964. As a divorced mother of five children aged from nought to sixteen, Anne had some trepidation about the future but also a strong sense she had made the right decision for her family.

A New Chapter: Focusing on Women’s Health, Family Planning, and Marrying George

The demands of family life meant Anne worked in part-time positions as time allowed. Her medical friends and colleagues provided crucial support; Anne’s interest in women’s health led her to reconnect with Sir William (Bill) Liley and Sir Graham (Mont) Liggins, both contemporaries at Medical School. She took a part-time position in research and teaching programmes on contraception, breastfeeding, and menopause at National Women’s Hospital.

She also remained in the Medical Women’s Association and was a member of the National Council of Women. Keen to support her children’s education, she served on the Pakuranga College Board. Building the house at 23 Rangitoto View Road, with its stunning views across the Gulf and a WWII pillbox at the bottom of the garden, proved to be an excellent decision. The children all loved swimming, and the boys took up sailing. The community was very supportive, and Anne felt she had finally established the stable base her family needed.

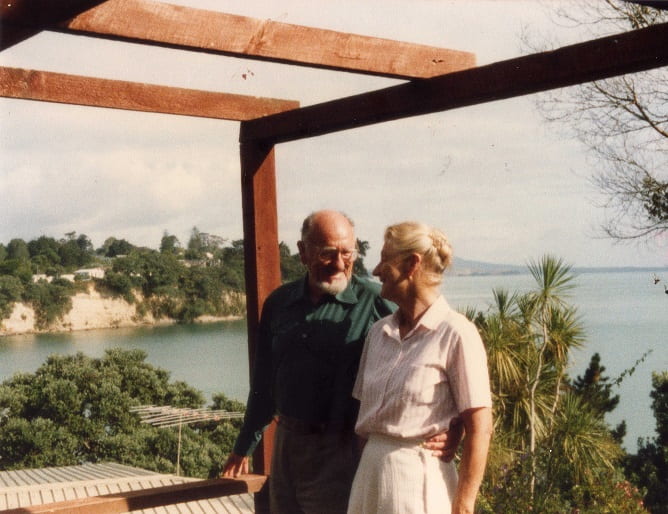

In December 1971, she married George Walmsley McKinnon, an industrial safety consultant. They had known one another for over a decade and had similar interests – family, work, travel, gardening, literature, music. A trip to Europe and the UK in 1976 to attend safety conferences and reconnect with Anne’s family and the purchase of a section at Little Bay, and later a bush block at Tapu, on the Coromandel Peninsula, were highlights for them both.

Anne continued to take part-time and full-time medical roles in the 1970s. Her work in women’s health was wide-ranging; in 1979, she was both a part-time Medical Officer of Special Scale (MOSS) in ante and post-natal instruction at Middlemore Hospital and involved in a research study on a new injectable hormonal contraceptive, Depo-Provera. Anne’s interest in contraception was long-standing and personal, from her first encounters with the washable rubber condoms in vogue in the 1940s. The contraceptive pill was liberating for many women, and Anne was keen to promote women’s autonomy in contraceptive choice.

She was also supportive of safe, legal abortion, as she saw this as a women’s health issue of critical importance. She had offered a home to several ‘unmarried mothers’ in the 1950s and felt strongly that they required constructive support, not criticism. She had been appalled by some of the attitudes towards women she had encountered when she first arrived in New Zealand and felt her work in this area of medicine was very worthwhile. This led to some conflict with old friends – she and Margaret Liley parted ways on the issue of abortion, but it also led to new alliances.

In the 1980s, Anne worked for Family Planning, as a part-time medical officer at their clinic in Otahuhu and other branches. This role drew both on her professional capabilities but also her life experience. She showed great compassion for women ‘in difficulties’ as she had once been.

Retirement Years

When she retired in 1991, Anne took up watercolour painting again after a hiatus of 50 years and looked for other ways to keep her mind alive. She had become friendly with Dr Zoe During, who had also brought up five children alongside a career in medicine. They discussed the idea of forming a University of the Third Age (U3A) branch in Howick. With friend Betty Berridge, they had formed a group of 45 people by the end of the year. Anne made long term friendships through U3A, and the group has continued to flourish.

George’s death in 1994, and the sudden death of her daughter Felicity in 2010, were devastating, but Anne continued to participate in U3A and other community activities. In her last years, family was her focus: Anne had ten surviving grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. Throughout her life, her resilience and her commitment to her values remained outstanding.

Anne passed away peacefully on 10 October, 2021, aged 97 years.

Bibliography

[i] Otago University Student Health Service Survey 1946: https://otago150years.wordpress.com/2016/05/23/the-class-of-1946/