This biography has drawn heavily on the information from her two autobiographies “Backblocks Baby-Doctor” and “Doctor Down Under”. (1, 2) Her grandson Tony Gordon supplied valuable information on the early history of the Jolly family; also he and her granddaughter Nicky Gordon supplied several photos. Further secondary resources are listed in the bibliography at the end. We are grateful for the assistance of Dr Ronald W Jones, current chairman of the Doris Gordon Memorial Trust, who kindly lent us the first two volumes of the minutes of The Obstetrical Society (B.M.A. N.Z. Branch) (3, 4)

Contents

The Early Years

Doris Clifton Jolly was born in Coburg, Australia on 10 July 1890 (5) Her mother, Lucy Clifton Crouch, was born in St Kilda, Melbourne in 1864 (6) and her father, Alfred Jolly, was born in Kooringa, The Burra, South Australia in 1861 (7). Doris was the second in the family; her brother Frank was born two years earlier in 1889. Her mother was the daughter of a prominent Melbourne architect Thomas James Crouch, (8) and the granddaughter of Rev Nathaniel Turner, an early missionary to the Bay of Islands. (9)

At the age of eighteen Doris’s father Alfred entered the service of the National Bank of Australasia in Melbourne. After four years with the bank, he left in late 1882 or early 1883, to begin four years’ probation in the Wesleyan church. He was ordained in January 1887 and later that year married her mother Lucy. He served as a Wesleyan minister in several parishes in Victoria prior to his resignation in 1894.

Lucy was brought up in a strict Victorian Wesleyan upbringing and left an affluent home in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda, to marry a Wesleyan minister, who had been raised in a less orthodox family, where the father was a mining engineer. Doris and her family enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle in the Victoria parishes of Coburg, and Eaglehawk until the financial crash of 1893. (10) Alfred resigned as a Wesleyan minister from his Eaglehawk, Bendigo parish in February 1894 due to his personal financial situation. He travelled to New Zealand alone in early 1894 in the hopes of finding a better life for his family. He became a clerk at the Wellington General Manager’s Office of the National Bank of New Zealand in July, 1894 (11) and later in 1894, he organized for his wife and two children to sail for Wellington. They arrived on 12 September 1894 on the Hauroto. (12) Over the next eleven years, the Jolly’s lived in five Wellington rental homes until they built and moved into their own short-lived-in home at Karaka Bay, Wellington. The family then settled in Tapanui, west of Dunedin from 1905 until 1910. (1) Her father was successful in his New Zealand banking career, rising to the position of General Manager of The National Bank, with their residence back in Wellington from late 1910. (11) In addition to his work at the National Bank, her father became well-known as a lay-preacher with both the Methodists and Presbyterians. (1)

Doris, in later years, thought what a strange picture they must have presented on their trans-Tasman journey, as ladies did not tend to travel unescorted, much less travel across the Tasman Sea. She recalls her mother displaying the last vestiges of her affluent past; wearing a sealskin coat and carrying a spacious travel purse in one hand and a canary in a gilded cage in the other. Doris was instructed to hang on to the side of her coat on the side where Dicky the canary was and not to let go. As her mother and Frank sprang on to the gangway of the ship, Doris decided she much preferred to stay in Australia. Her mother was half-way up the gangway before she sensed her desertion and required the assistance of a burly sailor who unwound Doris’s arms from the lamppost, tucked her under his arm, and carried her head first up the gangway kicking and screaming. To Mrs Jolly, who had left a three acre home in the affluent area of St Kilda prior to her marriage, the little matchbox the family moved into on Buckle Street, Wellington was an atrocity. (1)

One piece of furniture which had accompanied them from Australia was her mother’s cherry-wood German manufactured Thurmer piano. As they moved around the city to different homes, Mrs. Jolly supplemented her husband’s bank officer income by giving piano lessons to the local children, as well as Doris. Frank and Doris started out being home schooled by their mother; Frank was an avid student whereas Doris was disinterested and preferred roaming about in the outdoors. At the age of nine, Doris spent some time attending Miss Shepherd’s Academy for Young Women and later in Karaka Bay, at the age of twelve, she was sent to Worser Bay School where she spent the only year of unbroken education she was ever to receive in her childhood. At the end of this year she was given a standard five certificate. (1) From 1903 to early June 1905 when the family moved to Tapanui, she attended St Francis Xavier’s Academy in Seatoun but often had to look after her mother who suffered from “anginal heart attacks.” (1) Doris received prizes at the end of 1904 for English grammar, composition, geography and history, science, map drawing, oil painting and art needlework. (13) While at the Academy she is recorded as passing theory and practical exams in music. (14, 15)

The Call to Medicine

On their arrival at Tapanui, Doris refused to go to the local high school and, by this time her family knew that she succeeded only in the tasks which appealed to her. They decided music was to be her focus and housekeeping her livelihood. She became a very good cook and jammed, jellied and preserved in true colonial style. For four to five hours a day during the next school years she practised her music and eventually travelled to Gore in 1909 to perform for her senior Royal Academy examination which she passed with a mark of 103. (16) In tandem, Doris, along with her family, became Presbyterians when they moved into the southern Scottish community. Doris became a committed Sunday School teacher and soon had a class of forty children which her mother helped with by playing the organ. During this time the idea grew within her that she was being called to be a missionary. Then it was refined to being a medical missionary. The religious philosophy of the poets Browning and Havergal along with the missionary lectures she heard at church so haunted her that she resolved to become a medical missionary among the purdah-bound women of India. Shortly after her successful music exam she announced her intention to her parents as she sat between them around the fire: (1)

Do you know what I’d like to do next? I’d like to study, pass the matriculation, and go to university and become a doctor. “You study! they exclaimed together. “Yes”, I said meekly. “And what do you want to do if you are a doctor? asked mother. “She probably wants to be a missionary,” said my father, who was observant. He rose quickly to his feet and in a manner that was both a challenge and a promise said, “If you can pass matriculation, I’ll pay for you to study medicine.”

The local state school would not accept Doris without a sixth standard proficiency certificate. Her father’s friend at the Teacher’s Training College in Dunedin said he would examine her. She had three days to prepare the mastery of decimals. Although she only passed with 2.5 out of 6 in her sums, she received a standard six pass on the general excellence of her other work and was able to commence high school at Tapanui and was successful in obtaining her matriculation. Over the next eighteen months she worked extremely hard but algebra never made sense to her. She developed a simple examination philosophy: (1)

If I was meant to be a medical missionary, and if I’d done my best all these months it was God’s business to brighten up my dull brain at the crucial moment. If I failed ….. perhaps He didn’t want me to be a missionary and I could return to my beloved music. So my practice was, as each test-paper was handed out, to shut my eyes for a split second and breathe, “God, please help me make the best use of what brains you have given me.” Then I would look down the questions. When I opened my eyes on the algebra paper, seven out of ten questions, I saw, were the dreaded problems. The habit of Miss Campbell, our algebra teacher, was to wait for her “Matric” candidates on her verandah. On the afternoon of the examination we arrived with our papers and scribbled answers. Of the nine students, she looked at mine last. She looked up from the paper and looked at me. I looked inquiringly. She looked at the paper again, and once more at me. In puzzled astonishment, she said: “You’re the only one who has all the problems correct. However did you do it?” I was too shy to tell her God had done them: she might have thought it was cheating. But God had done them. I knew that no one else had; and all of those problems had been quite beyond me. Twelve weeks later I entered medical school of Otago University – probably the most poorly educated student ever to cross her threshold. The professors of Chemistry and Physics might just as well have been lecturing me in Arabic. I had come to a notion, if not to an estimation, of the breadth of my ignorance.

But there was a driving obsession to go ahead no matter what the difficulties, and this was more than the enthusiastic confidence of youth. The driving force was the canny Presbyterian conviction that I had the Almighty to reckon with and to help me. Indeed, I believed I’d entered into a humble and very junior – but very real – working partnership with Him. This notion may sound blasphemous to some, and quite orthodox to others. Nevertheless, out of this abiding sense of personal partnership with the All-Seeing, the All-Powerful, the All-Loving, came in some way that I can take not the slightest credit for, the ability to do many things which I had been told were impossible.

I must do my best here and now, forty years later, to record my feelings and motives then. Otherwise, this story of a half-educated country lass making a somewhat spectacular way through medical school, coming safely through a multitude of hazards, and living to see so many of her dreams come true, may deservedly be criticized as the talk of a self-made woman praising her creator.

Studying at the Otago Medical School

During her Medical Intermediate year in 1911, Doris settled into her boarding house on George Street which was within walking distance of Otago Medical School. She often burnt her kerosene lamp past midnight and her land lady fed her well at the mid-day meal with vegetables, meat and “Dunedin doughs.” Her boarding house was located next door to Knox Church and on her first afternoon in the city she was “trapped” by the minister into leading a young women’s Bible class. She had her mother’s old “Thurmer” piano installed into the Bible class room and led that class until the end of 1914. She gained much from this experience including the ability to speak without preparation in public. (1) During this first year she struggled between the theory of evolution being taught in her Biology classes and the trust she had in her creative God. Before leaving Dunedin for the summer vacation she went to see her minister and asked to borrow any books he had as an offset to Darwin and Huxley. She also received a request to be the woman speaker at the missionary night of the All New Zealand Bible Class Conference in Hamilton to be held over the new year. For three weeks she vacationed by the seaside with her mother and quietly struggled with the evolution issue. Following the conference address to 600 young people, where she kept them completely silent for twenty minutes, she asked the camp director to take her back to her room. She told the director “Something big has happened tonight and I’m not scared of evolution any more.” Earlier that evening she had shared the platform with “Mr. W.P.P. Gordon, M.A., son of the Marton Manse you know. He’s going to Dunedin next year to study medicine… he wants to be a medical missionary in China.” No one thought to introduce them and she did not have the slightest premonition that she would eventually marry him. (1)

Doris passed three of the four Medical Intermediate subjects which meant she was able to commence first year medicine in 1912, along with four other women students, while she repeated Inorganic Chemistry. (1, 17) She was also able to move into the newly opened St Margaret’s residential college for women students where she stayed during the rest of her medical training. She was bitterly disappointed with the May 1912 results of her Anatomy exam, achieving only 42 percent. Despite developing appendicitis in the autumn term of 1913, she learned much practical experience in the role of surgical patient and by November 1913, she had passed the first professional examination with top place in anatomy. (1)

In 1914, in order to obtain six deliveries, she would venture out with her good friend Mary Francesca “Francie” Dowling at all hours of the night, to both the Forth Street maternity hospital (founded by the Dunedin Hospital Board for the joint purpose of caring for “fallen women” and providing instruction in midwifery for medical students) and the Salvation Army refuge home for single girls which allowed only women medical students to attend births. The matrons in both homes felt that students were a menace to their mothers and habitually called them only when the birth was ten to fifteen minutes away as puerperal fever was still a most dreaded outcome in the maternity homes during that era and medical students were thought to be transmitters of it. Matron would stand over the students making sure they scrubbed for five minutes, masked and gowned while her second in command held the head back and the woman yelled for release. During these learning sessions, Doris developed a strong resentment against the whole plan of Nature which permitted women to suffer thus that life might be continued. She vowed that, if this was indeed the law of life, then she’d spend her days discovering some safe method of making it easier. She knew Queen Victoria had received chloroform to relieve her birth-pangs so why not the women in the slums of South Dunedin. From those first night-time callouts, she developed a belief in the equality of comfort for every mother. She was going to search for a safe, universally applicable method of pain relief. (1)

In her final year of medicine in 1915, the military and civil authorities were competing for young doctors. The medical school was suddenly having to supply junior Medical Officers to the armed forces. This resulted in the final year class of 1915 having their vacations cancelled and sitting the qualifying exams in October 1915 rather than the usual February 2016. (1, 18) In her final year, Doris had the good fortune to work with Dr John Tait Bowie who by his careful assessment of case histories and great skill in observation, percussion and auscultation, taught her to use her own powers for diagnosis rather than depend upon “modern machinery.” She believed this 8 a.m. clinical work eventually gave her top place in both the medical and surgical final examinations although her good friend Francie Dowling had the highest aggregate of marks over the five years and won the travelling scholarship. (1)

The House Surgeon Years at Dunedin

The first task that Doris’s mother organized on the Saturday morning following the news that she had passed her final exams was to get Doris some new clothes which would be appropriate for her role as a house surgeon. A navy suit was part of this new wardrobe. They then travelled to Oamaru in the afternoon where she planned to have ten days’ holiday before starting the fourteen hour days for the next twenty-six months. On the Tuesday she received a telegram telling her she was required urgently and to report on Wednesday for duty. Within a week of the entry of the four new pressure-prepared graduates who were successful in receiving a Dunedin Hospital placement, all the former house surgeon staff had gone to war and they were left to sink or swim. The experiences they gained during World War I were unique to them alone. (1)

Her good friend Francie, (who subsequently went into general practice work at Hawera and died in the influenza epidemic in 1918) (19) shared the experiences of a house surgeon with her. The women had rooms on the second floor of the south end administrative block of Dunedin Hospital and the men were housed on the north end. They all met for meals in a communal dining-room about twenty paces from the front downstairs door, which meant that at mealtimes they would exchange a review of their day as well as the hospital gossip. They also discussed the theatre manners and diagnostic ability of their seniors. They realized their former teachers sometimes had “feet of clay.” Surgery was only beginning to move away from the “cut-and-slash get-it-over-quickly technique” which had been necessary in the pre-anaesthetic days. Their seniors worked “roughly” by later standards which caused shock to the patient, anxiety for the anaesthetist, tension for the nursing sister, frayed nerves for the surgeon and frequent rude words for the house-surgeon. Seventy percent of the anaesthetics were given by the internee staff. Doris was grateful that Dr Bowie stood by each of them for the first dozen or so and only let them go solo when he was sure they knew the signals of light, medium and dangerous. He also stood by if he knew there was a particular risky anaesthetic to be given. (1)

Doris also had plenty of opportunity to observe the aftermath of abortions and venereal diseases. More women seemed to enter hospital for “treatment of miscarriage” in those days compared to the 1950s. They also remained longer, suffering from peritonitis, blood poisoning, or multiple abscesses of pyaemia. Often, men did not realize their promiscuity could give gonorrhoeal peritonitis to their wives or that it took two people to perfect birth control. In these years it was often the husband who insisted that his wife go to the abortionist to be rid of what he would call “her carelessness.” Doris’s first encounter with the work of an abortionist ended in the death of a mother of six little children who had been admitted with “a threatened miscarriage.” She had been observed for about four days when it was deemed the fetus was not living. Unbeknownst to them, a ragged hole had been made by a clumsy abortionist which the house surgeon and her senior had misdiagnosed during the D&C as a bicornuate uterus. Peritonitis had travelled up to the diaphragm during the previous four days and she subsequently died. Her brother, on hearing of her death, rushed to the hospital to say “I don’t care who I tell. She was my sister and her husband made her go to an abortionist.” There was an arrest and trial, but Doris said “as usual the abortionist got a thundering good advertisement and was acquitted.” On another occasion, Doris describes a “well-fed, navy-blue, pussy-footed policeman” stopping her one morning in the entrance hall of Dunedin Hospital and asking quietly if she had any women in her care whose state would tally with the discovery of a fresh human afterbirth found on the bleak land reclaimed from the harbour. He was not prepared for her reply: “I’ve no one that fits the story, and even if I had I wouldn’t tell you. We’re here to heal people, not pimp on them.” (1)

Her romance with William Patteson Pollock “Bill” Gordon had been slowly progressing during her house surgeon years. He wrote his final exams in February 1917 and they were married in Palmerston North on Good Friday, 6 April 1917. She and Bill returned to Dunedin six days later and moved into a small flat in Pitt Street. Bill, along with the other male medical students, volunteered for the war effort upon receiving their successful exam results at the end of their training. Without any normal civilian hospital experience Bill was off on Saturday, April 14th to Awapuni, Palmerston North which was the sole location for training the New Zealand Medical Corps during World War I. (20) He left for overseas on April 26th to serve in the war. (1) He rose to the rank of Captain and in mid-1919 returned to New Zealand as medical officer of the transport ship Pakeha. (21)

Commencement of Career

In addition to her hospital responsibilities, Doris took up a full-time University Lecturer position in bacteriology and public health under Professor Champtaloup. She also began working towards her Diploma in Public Health. She describes her creed in 1917: (1)

I felt that I touched Heaven whenever I laid my hand on a human body; and I, a relatively uneducated country-bred woman, could sometimes do things which seemed impossible because, when I was utterly certain in my heart that what I was doing was right, I believed that God was my senior partner.

In June, Professor Champtaloup developed pleurisy and Doris had to take sole charge of the laboratory. The Dean of the Medical School, Dr Lindo Ferguson, would drift by about eleven-twenty each day and would check to see if she had her class under control. It was always quiet. In late June, she also started making inspections of abattoirs, sewerage, food shops, dairy supplies, and food factories in pursuit of her Diploma in Public Health. (1) During the spring recess, as part of the requirements for her diploma, she had to spend three weeks obtaining experience at the Head Office of the Department of Health in Wellington and was introduced to “bureaucracy.” They’d forgotten she was coming and didn’t know what to do with her. It took utmost restraint for her to refrain from tidying everyone’s desk. She was amazed at the contrast between the anxiety and effort that went into a smallpox epidemic versus the file upon file on Mrs Smith’s duck-house. (1) This brief placement in the head office led to her realization that bureaucrats were frightened of newspaper publicity, an awareness she later used to good effect in her campaign for maternity reform. (22)

In October 1917, as part of her practical test for her Diploma, while she was standardizing the strength of a vaccine (using the routine drop of her own blood) she was stunned to see evidence of “tuberculosis at work somewhere in her body.” The chest x-ray confirmed there was a “spot of trouble” starting. She was told to get out of the laboratory, limit her working hours to three to four hours per day, then to take her study books up to the roof and rest in the sun whenever possible. Her Diploma exam was in five weeks. Afterwards, she spent ten weeks in the mountain air of Queenstown – a wonderful cure for tired folk with a “spot of tuberculosis.” The Wellington director of the Health Department then offered her a “very good position for a woman” which she declined. Her instinct warned her to “avoid state service, take the rougher, harder way of general practice.” Why not the director wanted to know. She replied: (1)

“You see sir, I’ve not struggled through seven years’ medical work to spend my life filling in red, white and blue forms about the situation of Mrs. Smith’s duck-house. By the way, how are those ducks?” The director roared with laughter, said that I was an impudent hussy and the ducks were all dead. Then he added, what do you propose to do if you will not enter my department? “Look round for a locum-tenens position – there must be many doctors who have not had a holiday since the war began.” “Yes, quite so, he replied. There’s my friend Paget in Stratford; he hates lady doctors, but might put up with you for a holiday. Shall I tell him you’ll relieve for him at the end of March?” And that is how Dame Destiny brought me to Stratford.

Dr Paget, who hated lady doctors, must have been impressed, as he offered her, in mid-1918, the position of his long-term locum along with his nine-bed hospital to mind while he went to help out the military. Theoretically, the practice she had taken over from him was considered a “light one” until November 1918 when the dreaded influenza pandemic arrived. It’s arrival almost coincided with the end of World War 1 and the resultant celebrations in all the cities and towns throughout New Zealand. Stratford was not spared. She sat with a sick woman in premature labour with a temperature of 104°F (40°C); Doris had her first rigor twenty hours later. She recounts: (1)

I realized that the situation was already out of control and no one knew how much worse it would get. As the time wore on, I had an idea. Dr Paget was due to pass through Stratford that very day. I’d get our lawyer to accompany me to the station, impress on him the serious situation amongst his own clientele, and beg him to detrain and help for the whole five days he was on leave from camp. We intercepted him and while we were asking him, I got the first shiver. Both gentlemen noted it and Dr. Paget said in his forceful way: “Home to bed for you. That’s the quickest cure. I’ll carry on alone. Coming up in thirty-five minutes to collect your list of calls. Away you go.” He was correct in his theory that the cure would be quicker in ratio to how promptly the victim gave in and went to bed. I was at work again in six days, very sorry for myself, but buoyed up because never in all my medical training had I ever expected to be responsible for lives in a Black Death Plague.

On the third day after Dr. Paget left I spent most of my time verifying that the victims of Armistice Day celebrations were pulseless and signing their death certificates. Someone in the capital had taken action and closed hotels, schools, churches, places of amusement and all non-essential industry. Authority had ordered funerals to take back streets and to hurry. Funeral processions were banned and often relatives had to help the overworked gravediggers. On leaving the home after signing the death certificates of two young people, in the car I nearly broke down, but instead drove to the Mayor and demanded that he use his authority to recall Dr. Paget for the duration of the epidemic. The military authorities by now realized the gravity of the disaster which had overtaken the civil community. Dr Paget came back with a military car and driver and established his own sort of martial law within six hours. He commandeered an empty shop and installed the Town Clerk as head of what was virtually a control tower for the district. Within one day he had emergency hospitals functioning in the school and an empty boarding-house. The magnificent women of the district somehow staffed these make-shift hospitals, and cooked on the most fantastic improvised stoves. The bellowing, unmilked cows, too, had their roster. Good-hearted “cockies” were motored around to milk – at least once a day – whatever herds the control tower knew could not be milked by their owner. The death figures ultimately showed that the Dominion had lost more civilian lives in five weeks that it had lost soldiers in five years’ warfare. As suddenly as it came, the influenza disappeared and Dr. Paget had time to observe that even the effort of hurrying to the telephone winded me. “Better go to Dawson Falls Mountain House and have a rest before I return to Trentham,” he said.

On Bill’s homecoming and return to civilian life in August 1919, he was able to relieve Doris of her locum duties. She then travelled to Dunedin to meet the examining doctors for the Presbyterian missions. They merely shook their heads and said, “No tropical life for you. We think you had better remain in your mountain climate, and go very slow for awhile.” (1)

Early Career

In 1919, Doris and Bill bought Dr. Paget’s Stratford practice and its small private hospital, Marire, and set-up their own joint general practice which was their base for the rest of their working lives. (23) True to her word, Doris and Bill developed the fine art of anaesthesia with pure chloroform inhalation, and gradually in later years switched over to open ether. With their combined seventy-four years of chloroform usage, they never had one mishap. In addition, their maternity cases were often given ‘twilight sleep’ (a combination of morphine and scopolamine) if the women sought partial or total oblivion from childbirth but they withheld it for those with twins, toxaemia or premature labour as they were expected to have ‘puny’ infants. Doris sat up at night monitoring her labouring women so they might have a good sleep. (1)

Early in her practice, Doris had the misfortune of four maternal deaths in her first two hundred deliveries – four times higher than the average in the early 1920s. The first was a woman who had already previously had a stroke; she dropped dead as she was packing to go home. The second was from a ruptured uterus; Doris was called when the arm was already hanging out of the vagina. The third was a woman who developed rigors on day four and died on day twenty from an undiagnosed gonococcus infection. The fourth case was under Bill’s watch and died of an eclamptic fit from which she never recovered. That was their first and last eclamptic death. In a small community, after four maternal deaths, the “lady doctor” was looked on with suspicion. They quickly set some ground rules: they expected their patients to be regular in their antenatal attendance and were told if they failed to report they would be tracked down with uncompromising thoroughness. She went on to have between two and three thousand births that were fondly known as “Dr Doris’s babies.” (1)

To complement her growing knowledge of midwifery and twilight sleep, Doris also added her own child birthing experiences. On 23 July 1921, at the age of thirty-two, she birthed John Bowie, thereafter, called Peter, and twenty months later, on 30 November 1922 she had her second son Ross Clifton. A third son, Graham Rothwell, arrived six years later, on 10 December 1927 and then on 18 August 1933, at the age of forty-two and after three miscarriages, she finally had her daughter, Alison Jean. Their four children provided them with hands on experience in children’s health, including infantile eczema, food allergies, juvenile convulsions, diphtheria, and facial burns. (2)

(L to R) Ross, Bill, Peter, Alison, Doris, Graham (Photo courtesy of the Gordon Family)

In 1924, Doris sent her thesis entitled “Scopolamine-Morphine Narcosis in Childbirth” to the London examiners for the New Zealand degree of Doctor of Medicine. Later that same year, Sir Lindo Ferguson, the newly knighted Dean of the Otago Medical School sent her a telegram “Thesis accepted with commendation, my personal congratulations on the work you do for midwifery.” Doris was successful in the clinical test but failed in the written section. She never retried the exam. She had written the thesis as she felt an “ordered statement on the general safety of Twilight Sleep should go to some representative body, and the examiners for the M.D. were the only accrediting group on the horizon.” She had far-sightedness as she wrote: (1)

A national recognition of the advantages of pain relief would place the whole art of obstetrics on a higher plane. Only doctors specially trained could give this treatment and as they would have to give more time and attention to each patient, we could expect to see a decrease in the obstetrical accidents now occurring through lack of expert care. In time, it would lead to the establishment of more and better equipped hospitals in which any reputable doctor should be allowed to attend his own patient, but with the proviso that there would always be at hand a skilled resident or consultant well trained to advise on pain relief and cope with the more severe complications …. This would cost money but …… in the womb of British womanhood lies the Empire’s progress and her strength.

In 1922, Doris became aware of the first “rumblings” of state control of medicine. She had done a Caesarean section for a case of central placenta praevia saving both the mother and her infant. A few weeks later, while in Wellington, she met the Director of Health, who said “They tell me you did a Caesarean section up there recently. We can’t have that. You country doctors must ask permission of my department before you do things like that.” To which Doris replied “By the time I’ve written asking your consent to do a Caesarean, and have waited for your answer, I’ll be able to send you the duplicate of the death certificate.” Nothing further was said about permits in obstetrical emergencies but that evening Doris told her father she could not get the Edinburgh Fellowship of Surgeons quickly enough so he offered a loan to enable she and Bill to go overseas as soon as a locum tenens could be booked. Her mother gladly agreed to look after her grandsons, Peter and Ross. (1)

In December 1924 they boarded a freighter for England with Bill acting as the ship’s doctor. Each day they did fifty pages of revision in preparation for Edinburgh. They planned to sit their exam six weeks after landing as they hoped to fit in a study trip to Vienna. They both passed, with Doris tied with Dr Leslie Averill also from New Zealand, for second place. Doris was the first women in New Zealand and Australia to secure a Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons. (24)

Prior to going for their ten weeks of study in Vienna, they were able to meet with Mr. Victor Bonney at Chelsea Hospital in London. He was recognised as the leading authority in Great Britain on the subject of obstetrics and gynaecology (25) and was expounding a new theory about puerperal sepsis, arguing the infection was already in the birth canal and was raised to a state of virulence by the bruising and exhaustion of labour. (1) The communal style of the labour wards, both at the famous Simpson Memorial Maternity Hospital in Edinburgh and in Vienna, seemed quite primitive to Doris. In Vienna, not one screen was used. The sister’s desk was half-way down the ward, and as a woman’s pains got stronger, she was moved closer to the desk. Doris and Bill came home via the Suez Canal, and in Perth they received a cable that her father had died at the age of sixty-one. Her consolation was that he had received their cable from Edinburgh advising him they had both passed. His investment in them had been worthwhile. (1)

On her return Doris wrote an article for the New Zealand Medical Journal painting a graphic picture of the multi-bedded Viennese labour ward which was promptly picked up by the women of New Zealand as a “major policy matter.” (26) Around this time, the Health Department was encouraging the closure of private maternity hospitals where women were able to labour in privacy. (1) In 1904, the government had set up seven public maternity hospitals (St Helens hospitals) around the country which provided subsidised maternity care and trained midwives. However, private doctors complained they were “taking their patients” and private maternity hospitals had continued to flourish. (27) The National Council of Women was also learning “pressure politics” – after an election twenty to thirty women leaders from around the country would meet and decide on the various items of reform and take them back to their branches and indoctrinate thousands of women. In election year they became a substantial pressure group with votes behind them. In 1928, a minister was confronted by four ladies with the following message: (1)

Women are now going into hospitals more and more for their confinements. The private maternity hospitals, of course, have private labour wards. What we seek is your assurance that in future all new public hospitals will have single-bedded, and soundproofed, labour rooms. The deputation did not mince matters and were quite graphic. Like a wise man he saw the writing on the wall and promised. That promise has been honoured ever since.

The Founding and Early Work of The Obstetrical Society

In 1926, Doris voiced a need for “an association of midwifery practising doctors, similar to the British Obstetrical Societies, to better their work, correlate effort and to speak with a united voice on obstetrical platforms.” It was reported in the New Zealand Medical Journal and in the spring of 1926, that an obstetrical society was to be founded, that the British Medical Association be asked to recognize it and that the inaugural meeting be held in Dunedin in February 1927, when the Australian Congress of Medicine would be assembled at the Otago Medical School. Correspondence, with the aims and objectives, went out to every doctor in New Zealand. (1)

Fed up with the shalts and shalt-nots from the Health Department, one hundred and eighty doctors signed as foundation members. A few doctors who had no prospects of begetting or delivering babies gave us the backing of their membership, saying, “You do well to found your Society, for what threatens midwifery today will threaten all branches of medicine tomorrow.” They took for granted that Bill would be honorary treasurer and I would be the pen-driving honorary secretary.

Doris’s brief encounter with Mr Victor Bonney in the Chelsea operating theatre had led to a blossoming friendship which resulted in the British Medical Association inviting him to visit “The Dominion” and to attend the New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association in Hamilton and to be present at the first meeting of the New Zealand Obstetric Society in the new Medical School buildings in Dunedin. (25, 28) In the exchanges of letters, he indicated a wish to see the backblock life of New Zealand and to meet doctors working in isolation, which The Obstetrical Society duly organized. He departed saying, “The finest country God ever made, the best rank and file doctors I’ve ever met, and the worst roads the devil ever designed.” His visit was a “tour de force.” The day he landed the Society handed him a list of defects in the local services, based mainly on the fact that the entire annual teaching budget for Obstetrics and Diseases of Women was £500, of which the lecturer received £340. Bonney, in every speech, hammered home that he was “amazed that such a progressive country had a Professor of Surgery and of Medicine but only a lecturer in Obstetrics and Diseases of Women. Did his listeners realize what this defect meant to the immediate future of the country….” The press reported extensively, and the Society’s programme of reform now had behind it the voice and authority of one of Britain’s most eminent practitioners. (1, 29)

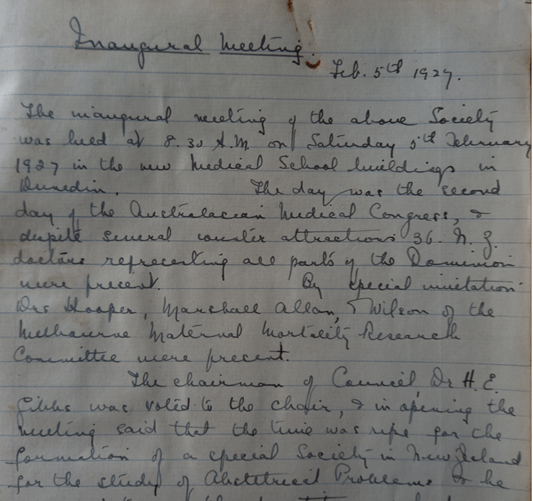

At the inaugural meeting on 5 February 1927 of the New Zealand Obstetrical Society (NZOS) later renamed the New Zealand Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society (NZOGS) in 1935 (30), Doris and Bill were elected to the joint office of Secretary-Treasurer, but by 1930 the roles were recorded in the minutes as Doris being the honorary Secretary and Bill the honorary Treasurer. (3)

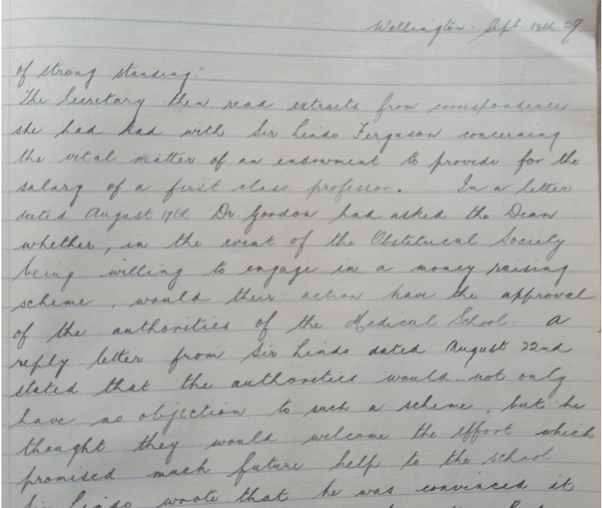

By 1929, the Dean of the Otago Medical School, Sir Lindo Ferguson, was having to replace the elderly Midwifery Lecturer, Dr. Riley. Sir Lindo was a man of world vision and knew the annual standard salary in Britain was £2000; he knew he had no prospect of obtaining a worthwhile teacher for less. He met with the executive of NZOS. They needed an endowment of £25,000 carrying pound for pound Government subsidy which would return a £2000 salary plus a little extra for departmental expenses. They brain-stormed and finally Doris came up with the suggestion of not looking for one benefactor but to seek out several benefactors. “A few of us would have to approach likely men. And you know, once we got a few giving a thousand each, the rest would be easy.” (1)

In her autobiography, Doris records: (1)

Half an hour later a resolution was passed that “The Executive endeavour to raise £25,000 for the endowment of a Chair in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, that the women of the Dominion be asked to help, that big donations be sought in the first instance, and that the honorary secretary and treasurer be empowered to proceed.” During the luncheon adjournment Sir Lindo filled me with fatherly advice. “Start as far away from Dunedin as possible. Never whisper that I encouraged you to do this. Do not come near Dunedin until you have got the whole campaign going well and” (impossible injunction) “let me see every letter you write for I am most jealous of the honour of my school and the reputation of my worthy underpaid teachers.”

In late 1929, Bill promised to run two practices while Doris “prospected.” The executive of NZOS endorsed a twenty-point communique to editors of all newspapers telling them the campaign would be launched on 19 February 1930. It quoted Mr Victor Bonney liberally and advised them the honourable secretary of the NZOS would call on all of them north of Palmerston North prior to 19 February. Prior to Christmas, Doris started in her own backyard with presentations to the New Plymouth Women’s Club and then the Taranaki section of the National Council of Women and outlined the defects in New Zealand’s obstetrical teaching. (1)

She fitted in a trip to explore the commercially rich city of Auckland. Sir Lindo had advised her to go first to Mrs David Nathan, an Auckland woman, who would be able to give sound assistance in the initial stages. Doris found Mrs Nathan was a bit of a dynamo and already had the campaign “all cut and dried.” She had divided up the “Dominion” into four population areas to work competitively over a six-week period – Auckland and Wellington were to raise seven thousand, five hundred and Canterbury and Otago five thousand pounds each. All four areas eventually exceeded their set target. (1)

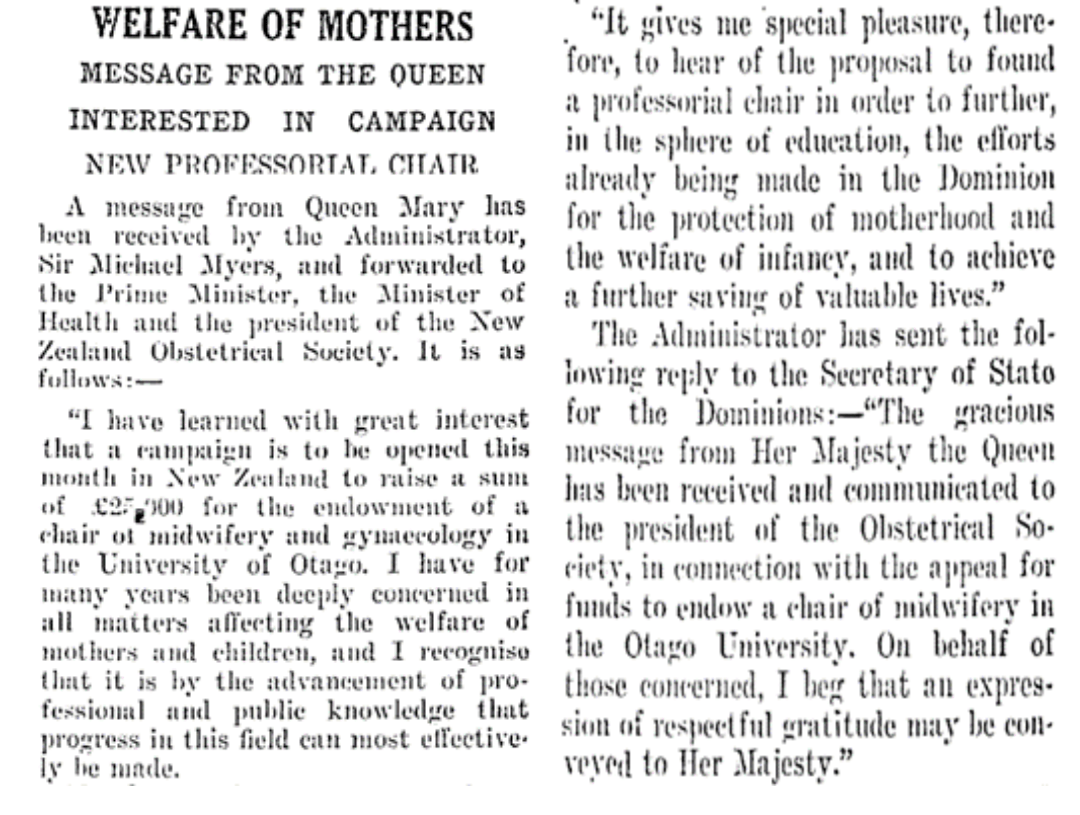

Meantime, she and Doris would have lined up business firms ready to grant a portion of their end-of-year dividends. She had already set up meetings and a speaking engagement for Doris on that first day – firstly, to meet her husband and another gentleman who would contribute £500 each to get the campaign started (once these men start giving, others will follow), then a lawyer of high standing who drafted the terms and conditions governing collection of the money, and finally an evening address to the Auckland National Council of Women. In addition, after Doris’s suggestion a message from Queen Mary at the strategic moment on 19 February 1930 would be useful, she took over making the arrangements for Doris to meet Lady Alice, the wife of Governor-General Sir Charles Ferguson, who was in residence in Auckland and was leaving New Zealand shortly. “Have you got white gloves with you?” (1) Doris travelled throughout the country, starting in the North Island, and moving south. Her efforts were often reported in the local papers. (31) Both Queen Mary (32, 33) and Mr Victor Bonney (34) wished every success to the appeal. The goal of raising £25,000 was met within the timeline.

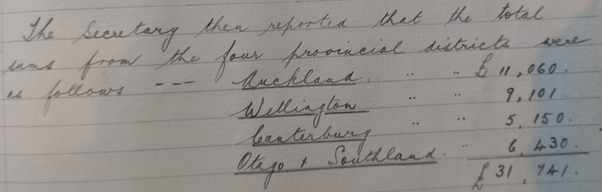

On 22 May 1930 the NZOS and several hundred representative women, entertained the Otago University Chancellor, Sir Thomas Sidey, and the Dean of the Otago Medical School, Sir Lindo Ferguson, at an afternoon tea where a cheque for £25,000 was handed over with the promise that there was approximately £6000 more to come. (1, 35)

It expressed the desire that the NZOS might be consulted in the matter of the appointment and on the personnel of the advisory committee; this was honoured. One representative from its executive would sit on every selection committee dealing with appointments to the Professorial Chair for Obstetrics and Gynaecology. (1) Doris wrote a nine page “Summary of Obstetrical Endowment Appeal Resulting in £ 31,741” which is included in the original minute book of the NZOS following the 31 May 1930 minutes of the Executive. (3)

In 24 June 1930 Stratford Evening Post, it was reported that the Otago University Council expressed that a special tribute be paid to the work of Dr Doris Gordon in helping to raise the funds. (36) The final surplus funds from the Endowment appeal were £6741 and in the NZOS minutes of 17 September 1930 it was resolved that “this money be deeded to Otago University for furtherance of Obstetrical Education in New Zealand, per medium of Travelling Scholarships and Research”.

In 1932, Dr J. Bernard Dawson, who had trained in the United Kingdom, arrived to take up the Foundation Chair in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, a position he held until 1950. He was a good leader and diplomat; over the next two decades he helped the Obstetrical Society transform midwifery from a “Cinderella service to the forefront of medical and civic thought.” (1, 37)

No doubt, Doris’s fundraising efforts were central in the recognition she was to receive from the British College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in 1933, of becoming one of their foundation members (38) and later in becoming a Member of the Order of the British Empire in the 1935 Queen’s Birthday Honours. (39)

Doris’s reflections on the NZOS and the NZOGS in her 1955 memoirs are enlightening: (1)

It was first conceived as a banding together of doctors to refute allegations that obstetricians were a forcep-interfering pest-bearing coterie. It had been formally proposed in Napier because a sanitary inspector — a man licensed to inspect drains – had presented himself before a surgeon of the English Royal College demanding reasons why the latter had done a Caesarean Section. This new bureaucratic curiosity was too much for the conservative dignity of Hawke’s Bay.

What the young society did between 1927 and 1937 by way of reducing eclampsia, routing puerperal sepsis and exposing the all too numerous interventions of abortionists is a chapter in local history itself…. Our aim was the genuine welfare of every mother, irrespective of colour or complexion, and her inviolable right to be treated with the same consideration as would be extended to a Prime Minister’s daughter…. Thus, when New Zealand became the first unit of the Commonwealth to go down the primrose path of socialized medicine, the midwifery service it handed out was superb. The New Zealand mother could depart to the hospital of her choice to have her baby, knowing that her own doctor would attend her there and that she would have an anaesthetist if necessary, and also an obstetrical consultant. Added to this was a full fourteen days’ of rest and care, and all at the State expense…. I never cease being thankful that New Zealand’s Obstetrical Society had evolved this blueprint of a model service, well before our country’s politics swung to the left.

The Depression Years

The years between 1930 and 1935 were thought of by New Zealanders as the mother and father of all slumps. However, Doris wrote in her autobiography that “we have never known, as the Old World knows, what real cold and hunger can be.” She was thankful that her parents had taught her to turn suits, feed hens and gather eggs before being taught arithmetic. Bill, as a penurious minister’s son, also knew domestic economy. Their cow was milked twice a day and a piglet fattened on the extra milk. Their boys did not seem to mind their patched clothing as they were well fed. Their lawn was dug up and crops of potatoes and other vegetables were grown. The barter system often became a form of payment with hens, a hogget, a half a bacon pig, or a couple of sacks of potatoes helping to feed themselves, their staff, and patients. One barber provided free haircuts to the Gordon males for two years. Staff took the universal 25 percent wage drop. Their hospital sisters were wonderful and knew housekeeping as well as nursing. One went on to become head of a city hospital and another the Nursing Director for South-East Asia under the World Health Organization. (1)

The Empire Congress

Doris was having frequent bouts of exhaustion and felt she needed a good holiday. On New Year’s Eve 1937, she informed Bill that she was going to take her middle two sons to Europe to learn German the following year in preparation for their medical school training. She and her two sons, Ross and Graham, plus a neighbour’s son Gavin left Wellington on 18 January 1939. She had letters of introduction from the Italian Consul to see Mussolini’s work for mothers and infants after the post-World War I era. She was given a leave of absence from the NZOGS honorary secretary position and was tasked with contacting all the New Zealand obstetrical scholars to find out why they were staying in the “home country” and not returning to New Zealand. She kept the boys to a study schedule as they crossed the ocean and was told on arrival in Italy, she had ten days to get her party out of the country. She got the boys settled into their boarding school in Lucerne, Switzerland. The following day Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia. Doris had planned to travel to Chicago to learn the latest in endocrinology from her Vienna friend Dr Schiller but needed to cancel that part of her trip. She arrived in England with a tide of European refugees on 27 March 1939. She gave her wardrobe and hair a much needed “renovation” and was amazed that in the fourteen years since she had been there, the country they called “Home” back in New Zealand was mostly run by foreigners in the centre of London. Each morning she woke wondering if she should take her boys out of Europe but then would have the “common-sense” response that “She was rearing men, not rabbits. Don’t teach them to run.” (1)

She attended the Empire Conference of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists held on 2 April 1939 in Edinburgh’s new Simpson Memorial Hospital. The first session was devoted to Pain Relief in Labour. The speakers became very technical and when two delegates stood up and damned the use of Chloroform “in Simpson’s own memorial hall” Doris could not contain her growing resentment and sent her name forward to the chairman to say she wished to speak. Immediately she regretted her impetuosity in this august assemblage of colleagues. Quickly, she decided she would bring the debate back to a working aspect. She commented that she could not contribute to the technical aspects of obstetrical pain relief but could add something to the practical. She advised in her own practice chloroform had proved safe and adaptable for all types of obstetric work and was useful in the remoter parts of the Empire. She suggested it would be a long time before they could hope to have their complicated apparatus, their syringes and sucker gadgets, functioning in the heart of New Guinea, or carried by canoe in Central Africa. But in the backblocks of New Zealand, they had proven that one could use the “little brown bottle” anywhere. The Hebridean Scot who had taught her made it clear that there was nothing wrong with chloroform if the person in charge of it was careful. She concluded with: (1)

I am glad to hear that science owed pain-relief to every woman. New Zealand had recently passed legislation giving free anaesthetics for every labour, but my country would need strong links with the British College of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists to ensure that its political promises did not soon degenerate into mere lip service.

Following the session, the President, Professor Sir William Fletcher Shaw, who was also partly responsible for creating the British College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in 1929, invited her to his home for a couple of days in preparation for their meeting with the “non-returning New Zealand obstetrical scholars.” Also, one of these New Zealand scholars, Dr John Stallworthy, invited her to come to the Nuffield Unit of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Oxford, to spend time with their top pathologist. The triangular friendship of Doris and these two gentlemen would eventually result in the beginnings of the Post-Graduate School for Obstetrics and Gynaecology in New Zealand. (1)

The meeting with the scholars soon identified the problem of them not returning to New Zealand. The chief reason was the hospital boards in New Zealand would not make any positions where these highly trained men could continue Obstetrics and Gynaecology as specialities. The hospital boards were unwilling to see gynaecology exalted as a speciality apart from general surgery. If the scholars stayed in Britain, they could get consultant provincial appointments at a retaining fee of £750 per annum and the right to private practice alone. New Zealand’s hospital boards did not offer such posts because of the influence of general surgeons who were reluctant to see gynaecology elevated to a speciality. (30) Shaw believed if New Zealand had one good Obstetrics and Gynaecology centre working well in New Zealand the results would change. He felt this centre would give impetus for other hospital boards to establish Obstetrics and Gynaecology units. Three New Zealanders – John Stallworthy, Professor Macintosh (an anaesthetist) and Doris met for a week and built on paper an imaginary Obstetrics and Gynaecology centre of eighty beds which would serve as a post-graduate school for the New Zealand doctors. Shaw advised Doris he would need to communicate to the NZOGS that the only chance of getting its scholars back is the founding of some such unit which would then encourage the establishment of others. (1)

By July 1939 Bill had joined Doris in England and they travelled to Switzerland to collect the boys’ heavy luggage so they could “flit at twenty minutes notice.” After the Russo-German Treaty of Non-Aggression was signed on 23 August 1939, Ross, her second born son, brought his younger brother Graham and his friend Gavin to Paris where they were met by Bill who had come across the channel on a London-Paris aeroplane. He wanted them to see a little of Paris and took them on a ninety-minute taxi tour the next morning before delivering the boys to the London Strand Palace Hotel at 8 p.m. The high commissioner had advised Doris they were to be evacuated from London that night as the London children were being evacuated the next morning. The family travelled to their Nanny’s relatives in Bath where the boys took part in wartime preparations – Ross helped sandbag the Admiralty at Bath then assisted with digging up the potato harvest. The younger boys walked over a tract of Wiltshire County, distributing leaflets on how to safeguard drinking water if the bombs blew up the sewers. With gas masks in tow, they made a few visits to London to view historical places before they all set sail from London at the end of October. (1)

The World War II Years

Back in New Zealand, Doris knew minimal progress would be made towards the establishment of an Auckland-based maternity hospital with a Post-Graduate Chair for Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and it would need to be put on the “back-burner” until the war ended. During a nightly vigil with a labouring woman in “twilight sleep” she took inventory of the old Marire Hospital with its outdated hotch-potch of architecture and decided they needed to build a fit for purpose hospital. Bill was against it as it would entail building at the peak of high war time prices, but Doris wanted the fun of working in a new hospital and “she was already fifty years old.” Bill stipulated that she get proper land surveys and then washed his hands of all responsibility. Doris had fun building the fifteen bed hospital and overcoming the obstacles of building during wartime. This included the county engineer coming each morning during the university break to give Ross, home from his first year at medical school, the correct levels in order to dig the six-foot-deep drains for that day. (1) The hospital was said to have been built along the lines of a private luxury hotel in order to provide the mothers who came to her every attention, in the most beautiful surroundings it was possible for her to achieve. (41) Doris and Bill were able to have a joint celebration in April 1942 as they celebrated with their Stratford community the opening of the new hospital as well as their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. (1)

In January 1942 Bill was recalled to the army and in early April was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel in charge of the hospital ship Maunganui. He was nearly fifty-five years of age. Doris felt the main reasons he was given this appointment included his immunity both to sea-sickness and to the fairer sex. He was unable to tell her whether their ship would be heading towards Australia and the Indian Ocean or towards Panama and England, only that he would be away a long time with possibly no letters but “she wasn’t to worry”… Their eldest son Peter, by this time a war time flight lieutenant and pilot for the Royal New Zealand Air Force, was able to dip his wings to his father as they sailed out of Wellington and advised Doris he was heading towards Australia. Farming news from Doris and little Alison’s letters to Bill were often shared with the maimed and homesick soldiers swinging in an iron cot between decks. An example of one of Alison’s letters shared: (1)

Last Sunday mother went to see the Jones of Toko and outside Mr Jones was grumbling because a sow had got eighteen babies under the hedge in April. He said he didn’t want April babies and thought he’d kill fourteen of the littlest ones. Mum said she’d like a girl pig from a litter of eighteen even if the mother wasn’t good looking. Mr Jones said we couldn’t bring it up on the bottle. But he said we could have ten of them if I liked. I brought one home and called her Weeny. I kept her in a box at night in the boiler cupboard and Sister Nancy and I took turns feeding her. All Mum’s patients seemed to know we had a bet with Mr Jones we could make the piggy live. We put her outside in her box during the day and for five days she looked good. Then she would not stand up, and in two more days the little pig died….

Post-Graduate Chair for Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Auckland

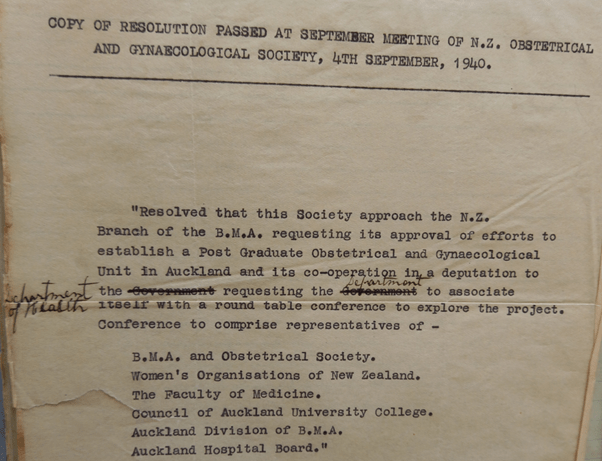

A post-graduate obstetrical and gynaecological unit based in Auckland was recognized as essential for medical graduates to gain residential midwifery experience without dependence on Britain. Dunedin was committed to training the medical undergraduates. The NZOGS, no doubt encouraged by the networking and background work Doris had done while in England, recognized that during the war years the momentum could be carried on.

On 11 December 1940, a conference was held by the NZOGS in the BMA Chambers in Wellington to discuss a post-graduate obstetrical and gynaecological unit to be based in Auckland. It was convened jointly by the Presidents of the NZ branch of the BMA and the NZOGS. Doris had been responsible for getting the Women’s Organisations on board. They recognized that through the women’s mass approval lay the road to political approval as they were a large voting block. (1) At this meeting delegates from various interest groups including the following ten women’s groups were represented, according to the minutes on page 191 of volume two of the original NZOGS minutes: (4)

- Dominion President of the National Council of Women

- President of the Women’s Institutes

- President of the Women’s Division of the Farmers’ Union

- Representative from the Canterbury National Council of Women

- Vice-President of the New Zealand League of Mothers

- Secretary of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union

- President Auckland Branch Obstetrical Society

- Chairwomen Auckland Women’s Committee for Better Maternity Services

- Delegate for Auckland Society for Protection of Women and Children

- Representative from the Wellington Branch New Zealand University Women’s Association

These groups had a far-reaching influence on the women of New Zealand. They went back to their local groups with ammunition for the cause of better maternity services. They raised the issue with their local politicians, and they were listened to, since election time rolled around quickly every three years. At this meeting the following resolution was passed:

Doris instigated the public appeal to finance the Post-graduate Chair of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. It raised £101,203 by 1947. (42) The first chair was appointed in 1951. (30) Sir Douglas Robb, campaigner for improved medical education in New Zealand and later Chancellor of the University of Auckland, saw this as the start of medical education at Auckland University. From 1964, the holder of the chair that Doris had established chaired the University Senate Committee to set up the Auckland Medical School. (43)

Auckland eventually got its women’s hospital – first the temporary military Cornwall Hospital built in 1943 which had accommodated the United States Army. It was acquired by the Auckland Hospital Board after the war and the first baby was born there in June 1946. (30) The new National Women’s Hospital was opened on 14 February 1964. (42)

Director of Maternal and Infant Welfare

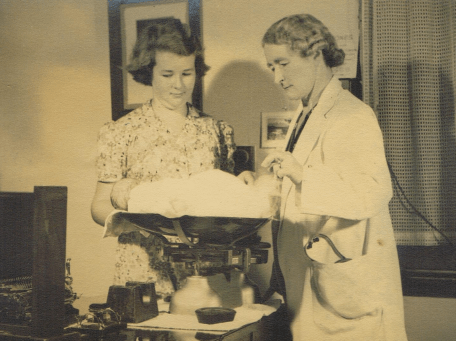

The appointment by the Labour Government Health Minister Arnold Nordmeyer of Dr Doris Gordon to the position of Director of Maternal and Infant Welfare in the Health Department was announced in late January 1946. It had the backing of the NZOGS as they wanted to keep “the Auckland project” on the radar of the government. The newspaper report said he was looking forward to receiving Dr Gordon’s recommendations for further improvements in New Zealand’s maternal and infant welfare. (44)

Doris appeared to be under no illusion that the Deputy-General of Health was not happy about her appointment. She felt he viewed her as “an uncompromising woman with a fierce zeal for mothers’ rights and a passion for cleaning up muddles.” (1) Her account of her years in the government department until her resignation in June 1948, are documented in her autobiography Doctor Down Under. (2) Prime Minister Peter Fraser asked her on her resignation:

Doctor Gordon, that book you are going to write. Will you write it in goodwill or in bitterness? I took the old man’s hands in mine. We had been friends in so many things that transcended politics, and political adversaries in only a few. ‘Mr Fraser, rest assured,’ I promised, ‘that anything I write will be solely for the long-term good of this New Zealand which we love so well. You have done your best. I have done my best. And time will be the Auditor.’

Final Years

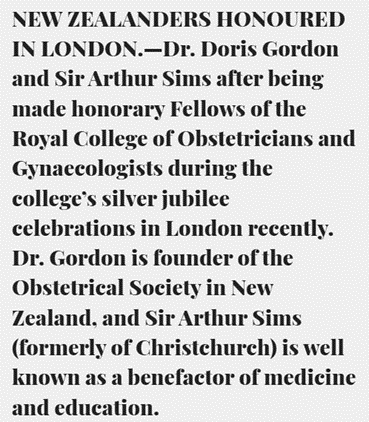

In December 1953, Doris received an unexpected invitation in the mail. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists wished, in connection with their Silver Jubilee Celebrations, to confer on her the Honorary Fellowship of the College in recognition of her great services to Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The only condition was that she must be present to be admitted. When her husband and son came in from the surgery for afternoon tea she informed them she was going to England and at the age of sixty-four, she would serve as the ship’s doctor. She decided it would also be a good opportunity to visit the publishers with her first autobiographical manuscript “Backblocks Baby-Doctor” which she had been working on for the past three years. Doris described her England visit thus: (2)

The highlight of my visit to England and in one sense the crown of all my work was of course the academic ceremony at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, where I had the great and humbling honour of becoming the first Honorary Fellow in the Southern Hemisphere and the only woman to ever to be so honoured apart from ladies of the Royal Family.

Her son Peter and his wife were in England at the time so were able to oversee getting Doris dressed in the appropriate finery and transporting her to both the afternoon and the evening ceremonies where she was presented to the Queen Mother. A few days later she was presented to the Queen and Duke at a royal garden party. (2)

Her Family

Doris’s eldest son Peter attended Lincoln College and the Nuffield School in farming in Crookston, Minnesota. He became an Otago farmer after the war and later became a National party politician. He was the member for Clutha from 1960 to 1978 and was a cabinet minister under Sir Keith Holyoake, Jack Marshall and Robert Muldoon. (46) He passed away in 1991. Her second and third sons Ross and Graham both obtained their MB ChB from Otago University. Both practised medicine in Stratford, with Ross specializing in Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Graham working as a part-time Surgeon. Ross became involved in local politics and was proud of having helped to fluoridate the town’s water supply, while a borough councillor. He received the New Zealand Order of Merit in 2001 and passed away in 2007. (47) Graham was active in his local division as well as the national body of the NZMA serving as council chairman from 1977 to 1978. (48) He passed away in 2004 (49) The Gordon family spent a cumulative 195 years in medical practice in Stratford. (47) Daughter Alison, attended Dunedin Hospital where she trained as a nurse. She graduated one year before her mother passed away. (2) Alison passed away in 2017 at the age of eighty-three.

In her second book of memoirs Doris describes the open home they had throughout their years at Stratford. After World War II, the Gordons sponsored thirty-two immigrants from the war-torn European countries including White Russia, Hungary, Serbia, East Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, and Holland. They all lived on the Gordon property and Bill especially enjoyed the stimulation of teaching the grammatical problems of English. They all went on to live productive lives in their new homeland. (2)

Ross and his family lived in a home beside his parents and Doris was able to enjoy her grandchildren for a few years. (1) She lived and practised at Stratford for 38 years before her passing on 9 July 1956 from a heart attack at the age of sixty-six years. Her husband Bill saw his last patient at the age of ninety. He passed away in 1980, twenty-four years after Doris’s passing.

In 2022, three Gordon grandchildren continue to live in the Taranaki region.

Outside of her medical career and family, Doris enjoyed her garden, their farm and playing social bridge. Throughout her married life, she embraced home-making and providing sustenance for her family and hospital patients. She embodied the biblical Proverbs 31 wife and mother.

Her Legacy

Throughout the Taranaki region and beyond, there were between two and three thousand citizens who described themselves as Dr Doris’s babies. Her horror at the treatment of young, single women during her medical school training translated into a missionary zeal to provide safe, pain free childbirth. Doris was devoted to midwifery care and believed all births should take place in a hospital and that mothers should be supervised by medical practitioners antenatally and postnatally. Although she was against state control of medicine, she was very positive about the Labour government’s midwifery service introduced in 1938 which provided for free hospital deliveries and fourteen days rest in hospital after the birth. She had a strong passion to provide a good midwifery education to the medical graduates of New Zealand. Through the efforts of the NZOGS she was able to provide a pathway for this vision.

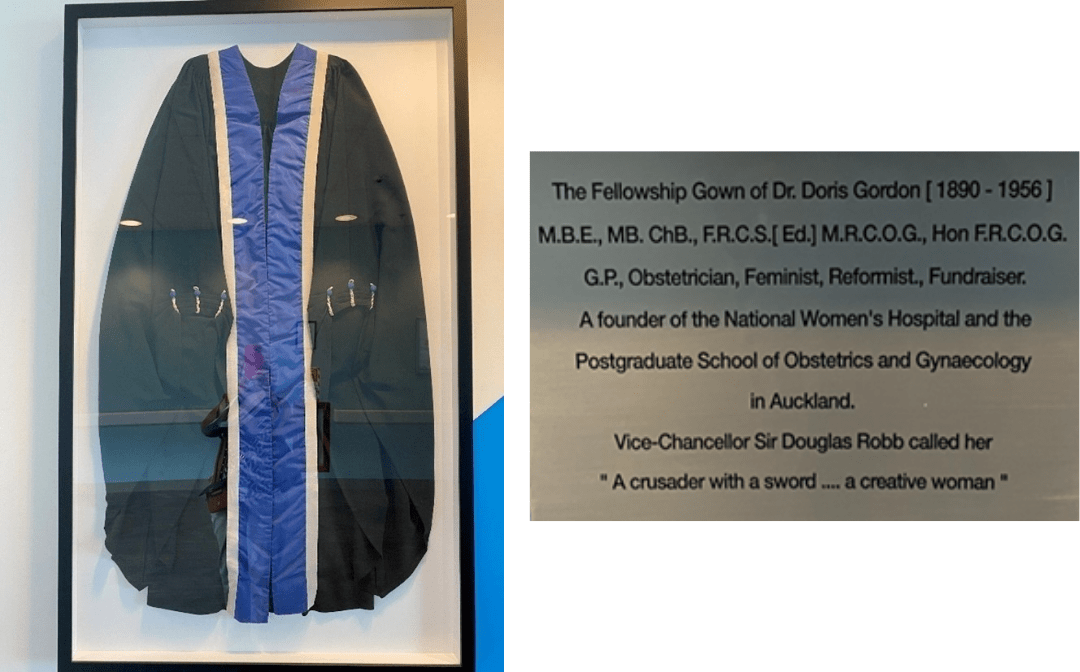

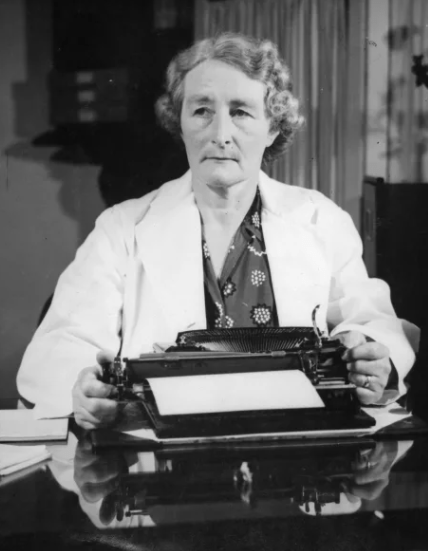

Her legacy lives on in her family, the families of the many ‘Dr Doris’s children’ and in the mothers and babies throughout New Zealand who have been the recipients of her commitment to making childbirth safer through the midwifery training of the “Dominion’s young doctors.” Today, she continues to be remembered at Auckland Hospital National Women’s Health through a display cabinet on the ninth floor which houses the gown she wore when receiving her honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in London in 1954.

Along with her gown is a picture with one of the seven typewriters she outwore through her many years of networking, lobbying, writing minutes and towards the end, the typing of her two autobiographical works. There is also a brief history of what Doris achieved during her lifetime and why she is remembered.

Along with her gown is a picture with one of the seven typewriters she outwore through her many years of networking, lobbying, writing minutes and towards the end, the typing of her two autobiographical works. There is also a brief history of what Doris achieved during her lifetime and why she is remembered.

Academic, author, wife, mother, feminist, and humanitarian. Dr Doris Gordon was above all a social reformer with a vision of a top-class obstetric and gynaecological service for all women. Undeterred by hostility and discrimination, Doris Gordon – great doctor and great New Zealander – exemplifies what all health professionals should strive to be. –Professors Linda Bryder (History) and John Werry (Psychological Medicine), May 2017.

Following her death, the NZOGS and the National Council of Women raised £4793 to establish the Doris Gordon Trust to “promote, sponsor, cooperate in, and otherwise further the study and/or practices of Gynaecology and Obstetrics.” Following its demise during the 1990s, a new Trust was established in 2016 between the New Zealand branch of the Royal Australian New Zealand Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (vis-á-vis the NZOGS) and the National Council of Women to promote education in women’s health including an annual Doris Gordon Memorial Lecture. (52)

At different challenging times during her lifetime, Doris was given fresh courage to stay the course through her strong Christian faith. In her autobiography Doris highlighted that the words of John Bunyan from Pilgrim’s Progress (53) provided her with fresh inspiration during some of these challenging times. (2)

My sword, I give to him that shall succeed me in my pilgrimage, and my courage and skill to him that can get it. My marks and scars I carry with me, to be a witness for me that I have fought His battles who now will be my rewarder.’…. So he passed over, and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.”

Bibliography

- Gordon DC. Backblocks Baby-Doctor: An Autobiography. 1st ed. London, England: Faber and Faber Ltd; 1955.

- Gordon DC. Doctor Down Under. London, England: Faber and Faber Ltd.; 1957.

- Minute Book of the Obstetrical Society (B.M.A. N.Z. Branch); 1927.

- Minute Book of the New Zealand Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society; 1944.

- Births. The Argus. 12 July 1890. Available from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/8416784

- Birth, Deaths and Marriages Victoria Victoria, Australia: Victoria State Government. Available from: https://www.bdm.vic.gov.au/research-and-family-history/search-your-family-history.

- Genealogy SA Adelaide: Society Library & Research Centre; [cited 19 April 2022]. Available from: https://www.genealogysa.org.au/resources/online-database-search

- Bolger P. ‘Crouch, Thomas James (1805–1890)’; Australian Dictionary of Biography Melbourne: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University; 1969 [cited 19 April 2022]. Available from: https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/crouch-thomas-james-3296

- Obituary Mrs L. C. Jolly. Manawatu Standard. 19 September 1939. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19390919.2.108.5

- Wikipedia. Australian banking crisis of 1893 [updated 16.08.2021]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_banking_crisis_of_1893

- Archivist NB. Unpublished history of the National Bank: Alfred Jolly. 1994.

- Shipping Telegrams. The Press. 1894. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP18940913.2.54

- St Frances Xavier’s Academy. Evening Post. 20 December 1904. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19041220.2.11

- Musical Examinations. New Zealand Mail. 30 September 1903. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZMAIL19030930.2.36

- Music Examinations. New Zealand Mail. 20 September 1905. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZMAIL19050920.2.5

- Musical Examinations. Mataura Ensign. 9 December 1909. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ME19091209.2.21

- University Results. Evening Star. 3 November 1911. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD19111103.2.41

- Medical Examination. Dominion. 14 September 1915. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DOM19150914.2.55

- Personal Death. Wanganui Herald. 23 November 1918. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WH19181123.2.39

- Restored Memorial To WW I Medics Rededicated Wellington: Ministry for Culture and Heritage; 2016 [cited 20 April 2022]. Available from: https://ww100.govt.nz/restored-memorial-to-ww1-medics-rededicated

- Personal Column. Taranaki Herald. 13 June 1919. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH19190613.2.8

- Jones RW. Honouring Doris Gordon: the foundation of a legacy. O&G Magazine. 2016;18(3).

- Bryder L. ‘Gordon, Doris Clifton’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography: Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; 1998. Available from: https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4g14/gordon-doris-clifton/

- Double Medical Pass. Auckland Star. 14 May 1925. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19250514.2.89

- A Noted Surgeon To Visit New Zealand. Evening Post. 6 June 1927. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19271206.2.66

- Gordon DC. Comparative Obstetrics. New Zealand Medical Journal. 1925;25(126):65-81.

- Bierman J. Kelvin Private Hospital, later Kairahi Guest House, 34 (22) Clonbern Road, Remuera: Remuera Heritage; 2020. Available from: https://remueraheritage.org.nz/story/kelvin-private-hospital-later-kairahi-guest-house-34-22-clonbern-road-remuera/

- Noted London Surgeon: Visit of Mr Victor Bonney. Taranaki Daily News. 23 March 1928. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TDN19280323.2.77

- Maternity Problems. Importance of Obstetrics: Mr Victor Bonney’s Advice. New Zealand Herald 12 March 1928. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19280312.2.102

- Bryder L. The Rise and Fall of National Women’s Hospital A History. Auckland: Auckland University Press; 2014.

- Active Campaign: Statement by Dr. Gordon. Evening Post. 4 March 1930. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19300304.2.83.3

- Obstetrical Appeal Fund. Wanganui Chronicle. 25 February 1930. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WC19300225.2.42

- Welfare of Mothers: Message from the Queen. Nelson Evening Mail. 25 February 1930. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19300225.2.108

- Obstetrical Appeal. The Sun 24 March 1930. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/SUNAK19300324.2.76.1

- Public Subscribe £31,741 to Fund: Success of Appeal by Obstetrical Society. The Star. 22 May 1930 Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TS19300522.2.168

- Obstetrical Appeal – University Council’s Appreciation. Stratford Evening Post. 24 June 1930. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/STEP19300624.2.44

- Science of Obstetrics World Maternal Mortality: Professor J.B. Dawson Interviewed. Otago Daily Times. 13 February 1932. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19320213.2.46

- Dr Doris Gordon, High Honour Proferred. Manawatu Standard. 22 March 1933. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19330222.2.118

- Invested with O.B.E. Dr. Doris Gordon at Informal Ceremony. Stratford Evening Post. 23 March 1936. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/STEP19360323.2.15

- Dr. Doris Gordon, M.B.E. Evening Post. 3 June 1935. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19350603.2.73.26

- Maternity Hospital Trust Gift by Dr Doris Gordon. Press. 14 August 1951. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19510814.2.4.7

- History of National Women’s Hospital Auckland District Health Board. Auckland 2010.

- Bryder L, Werry JS. Doris Clifton Gordon (1890-1956). Auckland Hospital National Women’s Health 2017.

- New Director Maternal Welfare: Dr Doris Gordon’s Post. Otago Daily Times. 31 January 1946 Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19460131.2.33

- New Zealanders Honoured in London. Press. 1954 [cited 21 March 2022]. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19540726.2.52

- Peter Gordon (politician): Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 1 October 2021; 2 May 2022]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Gordon_(politician)

- Wood R. Obituary: Ross Gordon. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2007;120(1260):88-9.

- New Zealand Medical Association History. https://www.nzma.org.nz/about/history

- Carey-Smith K. Graham Rothwell Gordon. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2004;117(1195).

- The Origins – FMHS 1883-1968 Auckland 2019. Available from: https://fmhs-history.blogs.auckland.ac.nz/home/origins/

- Smith PM. Doris Gordon 1890-1956. In: Macdonald C, Penfold M, Williams B, editors. The Book of New Zealand Women, Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books Ltd.; 1991.

- Jones RW. Doris Gordon: foundation of a legacy. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2016;129(1437):71-6.

- Bunyan J. Pilgrim’s Progress, Part 2: Christiana. 1685.