This biography is largely based on written material from the memories of John, Adah’s brother, archival material supplied from Nga Tawa College’s archivist Sally Patrick, and Maraetai historical material from a local resident, John Scott, who knew Adah personally. A full bibliography is at the end of this biography.

Class of 1930

Contents

Family History

Adah Hamilton Evelyn Platts-Mills (known as “Deed” in her very early years) (1) was born on 18 November 1904 in Karori, Wellington to John Fortescue Mills (known as Jack) and Dr Daisy Platts-Mills (nee Platts). She had an older brother Edward born in 1903 and a younger brother John born in 1906. (2)

Adah’s grandfather, Edward William Mills, arrived in Wellington in 1842 and as a teenager went off to the Australian gold rush where he soon discovered providing material to the prospectors was more lucrative than prospecting. (1) According to John’s memoirs, his grandfather made a fortune, and returned to Wellington where he set-up the hardware and engineering firm E. W. Mills and Company Ltd in 1854 which amalgamated with the Wellington branch of Briscoe and Co. in 1932. (3) He built a grand house on Aurora Terrace in the suburb of Kelburn which he called Sayes Court and had a large family of five daughters and four sons.

Adah’s father Jack was the youngest son; he was associated with his father’s company for many years but according to his son’s memoirs he was mostly kept at home to tend the family’s horses, dogs, carriages and to act as guardian and keeper of his mother and sisters and his most outstanding achievement was finding Daisy Platt to be his wife. (1) Jack was also prominent in Wellington rowing and sporting circles, being a member of the Star Boating Club as well as Hunt, Racing and Polo clubs. (4) According to his son, it was fortunate that Daisy wanted to work because her salary was needed. His father was not a good money manager and went through his inherited family money twice. John’s memoirs indicate the family generally did not have an abundance of money. (1)

Adah’s mother, Daisy Elizabeth Platts, was born in 1868 to Emma (nee Walton) and her husband, Rev. Frederick Charles Platts, an Anglican clergyman, (5) at the parsonage of Holy Trinity Church, Sandridge (now Port Melbourne), Victoria, Australia. Daisy’s father was born in Barrackpore, Bengal, India on 5 November 1823 and died on 28 May 1900 at the age of 76 in Port Chalmers, New Zealand. He came from an old Nottinghamshire family and was the son of Captain Robert Platts of the old East India Company army. He graduated with his M.A. from the University of Aberdeen and taught in a college in Delhi and later as a Classical Master at Bedford Grammar School, England. He came out to Australia at the direction of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel and had a parish in North Adelaide which stretched 400 miles north of the city. (1, 6) Adah’s maternal mother, Emma Walton, was born in Leeds, England in 1831 and died in Victoria, Australia in 1873 at the age of 42. (7) Her grandfather remarried and in 1880 moved his family to Port Chalmers where he became the vicar at Holy Trinity Anglican Church. (5)

Like many of the early women medical graduates, her mother Daisy attended Otago Girls’ High School (5) and entered the University of Otago Medical School sometime during her twenties. Prior to embarking on her university studies, she spent six years working as a governess in Central Otago. (8) This may have been to accumulate funds to support her university education, but this is only speculation. She came to Wellington in 1901 and established her own private practice, the first woman doctor in private practice in Wellington. The following year she married Adah’s father Jack. (5)

Early Childhood

Adah and her brothers’ childhood were spent in four different Wellington homes with the majority of their childhood years spent in the suburb of Karori. Adah, recalls that Daisy combined medicine and home life and remembers her as a splendid cook. (9)

During a downturn in the family “fortunes”, from 1913 to 1916, their home and her mother’s private practice were located at 81 Abel Smith Street in the suburb of Te Aro – an area known at that time as the medical heart of the city. (9) It was here in the kitchen, her brother John recalls, that he, Adah, and Edward had their childhood operations of removal of tonsils, adenoids, and appendixes. A surgeon would come to their home where they would be laid out on the kitchen table which had been scrubbed and pumiced until it shone, then varnished and disinfected. Chloroform was used for the anaesthetic agent. (1)

Adah recalls she and her brothers working together to make a bit of pocket money – they cut their holly hedge in Karori and filled her mother’s car with the trimmings to take into the city to sell to the florist. They were paid fifteen shillings for their efforts. She also reminisced about their mother’s name. They would often be sent to the local store for provisions and would ask for it to be put on the account of Dr Platts-Mills. The shop keeper told them it was a “magic name”. (10)

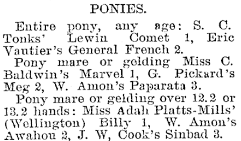

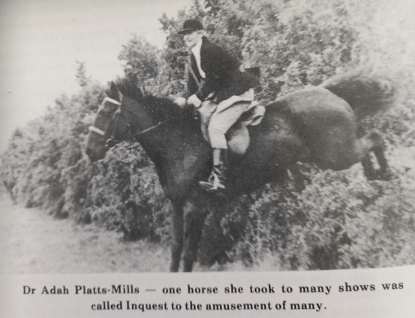

From Papers Past we can surmise that Adah’s childhood upbringing included some training in music, (11) dancing, (12) and horsemanship – she could remember her first ride at the age of five and had her first pony shortly after. (13) She attended the Manawatu Show on 1 November 1917 with her pony Billy and came first in her category. (14) This interest in horses was carried over into her adult years. (13)

Nga Tawa Boarding School Years

We are uncertain what Wellington school Adah attended during her early childhood years but in February 1918, at the age of thirteen, Adah was sent to Wellington Diocesan Collegiate School for Girls – Nga Tawa, Marton, an Anglican girls’ boarding school, which was run by the headmistress Miss Molly Barker. It was located on twenty acres of farmland about two kilometers from Marton. Most of the students came from fairly well-off families and the majority were sent there for their secondary education only. (16) Billy, her pony, accompanied Adah as the school permitted each girl to take a pony to school, a tradition which has continued almost unbroken over the School’s existence – Adah reminisced that this is what “seduced” her to into going. (13, 16) The practice served a dual purpose, providing a means of transport and as a solace for homesickness. Families could only come three times each term for visitors’ day. The girls would be taken out by their families to the White Hart Hotel at Marton, or on a picnic. The distance from Wellington was about 175 kilometers so Adah’s parents may not have been able to make this long journey regularly. (16) In her interview at the age of eighty-seven, Adah indicates some regret about being sent to boarding school as she missed out on these five years with her mother. (10)

The dress code during her time is shown in the photo above. For evening wear a black velvet frock with white lace collar and cuffs was worn. In summer, they wore a royal blue cotton dress and, in the evenings, changed into simple summer frocks in any style or colour. Black shoes and stockings and corsets were worn on all occasions. Sunday attire was a white linen coat and skirt with a boater hat, blouse and tie. For riding Adah would have had to wear a long navy divided skirt and black lace-up boots. (16)

The academic syllabus included ‘divinity and church history, English, history, geography, writing Latin, French, German, mathematics and natural science’. In addition, there were lessons in social accomplishments including ‘class singing, drawing, painting, plain needlework, drill, deportment and swimming’. A typical day began with a compulsory early morning bath, breakfast in the dining room with morning lessons to follow. The main meal (usually meat, vegetables and pudding) was served at midday, followed by afternoon lessons and then some free time prior to the evening meal at 6:00 p.m. This consisted of bread and butter, or bread and jam. Prep was done between 7:00 pm and 8:20 p.m. with ten minutes to eat a biscuit before bedtime. Miss Barker would then visit each dormitory to read to the girls and wish them good night. (16)

The five years, from 1918-1923, would have been memorable for Adah and her fellow boarders as significant changes and events occurred over these years:

- Adah started at Nga Tawa during a phase of rapid growth. From 1912 – 1920 the roll increased from 30 in 1912 to 62 in 1920 under the very capable leadership of the headmistress Miss Mary Frances Barker. Under her leadership the school had employed several young Englishwomen to assist in the teaching program. They were improving and bringing the school curriculum more in line with the state schools. This would have been important to Adah’s mother who had strong aspirations for her daughter to advance her career prospects (preferably medicine) beyond secondary school. From 1912, the academically inclined pupils at Nga Tawa sat both Matriculation and the Leaving Certificate of the Association of Headmistresses’ of Private Schools.

- The pupils started the 1918 school year with World War I still in progress. They took part in knitting and sewing projects for relatives serving overseas and for the Navy League. With the rest of New Zealand, they joined in the celebration of news of the Armistice being declared at 11:00 a.m. on 11 November 1918. The girls had a full day of celebrations including a march through the town of Marton, and a Thanksgiving service at the end of the day. (16)

- The Prince of Wales, Prince Edward, visited Marton in May 1920. Miss Barker and the archdeacon’s daughter, a student at the school, were at the station and a photo album of pictures of Nga Tawa School was presented to him. In her report to the diocesan secretary, Miss Barker wrote: “When the Prince walked through the ranks of school children – ours were standing in very correct uniform, strictly at attention, and he raised his hat, a compliment that no other school gained.” (16)

- At the beginning of the second term on the 6 June, 1920, the girls returned to school and enjoyed the usual opening service on the Sunday afternoon. On Monday morning they were shocked to learn that during the night their headmistress had suffered from a cerebral haemorrhage – she died before noon. In his funeral message Bishop Sprott said she was like a respected elder sister to her students, had lived for them and finally gave her life for them. The school had an interval of a few interim acting headmistresses before once again gaining stability in February 1921 with the new headmistress from England, Miss Frances McCall. (16)

In 1922 Adah passed her matriculation exams and was a prefect during the 1923 school year. (16)

Victoria and Otago University Years

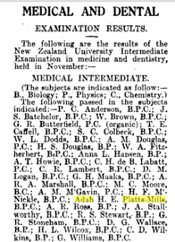

At the beginning of either 1924 or 1925, Adah and her younger brother John, entered Victoria University College and started their studies towards their Medical Intermediate qualification. He indicated they felt they “owed” it to Daisy to become doctors” (1) whereas Adah said “My mother more or less decided I was to become a doctor”. (13) She thought she was the last person to ride a horse to university in Wellington and her dog went as well and waited by her jacket in the cloakroom. (13) John switched to law after one month. He was unsure if he switched for fear of competition from “Deed” or for fear of exposing her to competition. His university scholarship was primarily based on chemistry, physics and maths, while she had a greater depth in zoology and biology. (1) At the end of 1925, Adah had passed her Medical Intermediate in Biology, Physics and Chemistry and was accepted at Otago Medical School for the start of 1926. (18)

Little is known about Adah’s Otago University years. She progressed through her years without failures, achieving her first professionals at the end of 1927, (19) her second professionals at the end of 1928, (20) and her third professionals and M.B. Ch. B. at the end of 1930. (21) She attended her capping ceremony in July 1931. (22)

House Surgeon Years

Her two years as a house surgeon were spent at Wellington Hospital during 1931 and 1932. (23) In her interview Adah said several house surgeons left to go to other hospitals due to “poor food” – it was the start of the depression. (10) However, in a Papers Past report, it would seem the catalyst may have been a ten percent cut in their wages due to “living in” accommodation being provided. (24) Perhaps the house surgeons felt the food being provided did not warrant this reduction in their wages. According to Adah, many hospitals were happy to accept the disgruntled house surgeons, but she was happy to stay in Wellington as she didn’t mind the food and her parents lived in Wellington. No doubt being close to her beloved horse was also an incentive. Wellington Hospital was left short on junior staff and one memorable occasion for her was during the 1931 Napier earthquake. She was the junior orthopaedic house surgeon at the time and remembers having to cope with many critically injured who were sent down to Wellington on cattle trucks. She mentions a night sister she met several years later who remembered her as a very hard worker during those years. (10)

Early Career

Following Adah’s two years as a house surgeon, she left Auckland by the “Waimana” for England in February 1933. (23) She had been nominated for the Manchester Research Scholarship (unable to confirm if she was the successful recipient) and her intention was to spend two to three years in post-graduate work in midwifery and gynaecology before returning to Wellington. (25) She was employed at the British Hospital for Mothers and Babies in the Woolwich district of London and in March 1934 was successful in gaining her Diploma of the College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, London. She was in the first class to achieve this diploma. It had been initiated to raise the standard of practice of these two disciplines amongst general practitioners. Following this achievement, she went to St James’ Hospital, a 1000 bed hospital in the London suburb of Balham, where she was employed as an anaesthetist. (26)

In May 1934, her mother and father travelled to England for an extended visit to see Adah and their son John who by this time was practicing at the Bar in London. (27) Adah worked in private practice for two years in Bournemouth on the south coast of England where her parents resided with her. (28) The climate was not conducive for their health so in late November 1936 they all returned to Wellington. (29)

On her return Adah accepted an appointment with the school medical service of the Health Department in Wellington and commenced her duties in early 1937; this included a short period in Palmerston North. (28) She was employed in this position for over two years and appears to have taken a strong interest in the diet of the school children. The report of findings on the health of the children at Terrace End School, which was requested by the headmaster, indicate that Dr Adah found defects in their diet was the main weakness contributing to poor health and attributed this to a general apathetic attitude towards diet. Her particular concern about diet was the excess of starchy food in the children’s lunches (sandwiches consisting of white bread, butter and jam, biscuits, and cakes). She encouraged the substitution of whole meal bread as a starter. She also indicated in the report the benefit of the dental clinic as a number of children were suffering in their general health due to lack of appropriate dental care. (30)

In early 1939, after her two years in the school medical service, Adah set up her own medical practice in Park Street, Foxton, (32) an agricultural coastal town about 115 kilometers north of Wellington with a population of 1600 and only one other GP (nearing retirement). The town had several flax mills during the period Adah was practicing here. She became involved with the Red Cross Society and the St John Ambulance, providing governance, class instruction and assistance with examining the students. (33-35) She was there from 1937 until the end of 1943 and was very busy during the World War II years as she had to provide some service to the nearby town of Levin as well. One particular scheme she promoted was in the area of cows getting tuberculosis (TB). From her interview, it seemed the practice was that if one cow in a herd contracted TB all were isolated and either treated or slaughtered by the veterinarian – it is unclear in the interview. She suggested that all cows with a negative test be put in separate paddocks and that they be closely watched and only cows with positive tests needed to be treated by the veterinarian. This practice led to the saving of many still productive cows. (10) While in Foxton, after fourteen years she was able to once again have her own horse. She rode every morning at six o’clock on the local racecourse and even raced in some official races. (13)

Possibly due to her father’s health, by early 1944, Adah had moved to Auckland and was living with her parents in Remuera, Auckland. On 5 February 1944 her father John F. W. Mills, at the age of 76, passed away following a short illness. No doubt Adah’s own life-long interest in horses was nurtured by her father who was reported to be a keen member of the Hunt, Racing and Polo Clubs. (36)

She worked at Auckland Public Hospital as an anaesthetist (10) and in April, opened a medical practice in the Dingwall Building in Queen Street for the next two years. (37) She continued living with her mother who passed away in Auckland twelve years later on 1 August 1956. Adah had two horses which she would take over on the ferry to the “north shore lake” (Lake Pupuke) to assist with giving lessons to children. She also used them in the Pakuranga Hunts. (13) There wasn’t enough grass in the field where she was keeping her horses near her Remuera home, so she purchased a three acre “gentleman’s residence” at 10 Kolmar Road, Papatoetoe and set up a medical practice there which she really loved – in her interview she referred to it as a “demure practice”. She continued to live here, with her mother, until circa 1950. (10, 38)

Marriage

A young man, Charles “Dudley” Blomfield, came to help Adah with her horses at her Papatoetoe stables. She taught him to ride, and he eventually bought a horse and joined “The Hunt”. Adah married Dudley circa 1950-1951. Little is known about Dudley except that he served in the New Zealand Air Force during World War II between 1939 and 1945 and the Auckland War Memorial Museum were able to confirm his date of birth as 08 August 1923 – eighteen years younger than Adah. (39) In her interview, she briefly mentions she met a man with a mutual interest in horses whom she married but later divorced. Dudley did not like Papatoetoe, so circa 1951 they had moved to Whakatane, where his parents lived. (10, 40)

In her 1992 interview with the Horse and Pony magazine, Adah recalled she had bought ninety acres of land which turned out to be a huge gully and a hill in the middle of Whakatane. Dudley built a beautiful barn on the site where they initially lived but she had to later buy a house in the town so she could practise without interruption as, during wet weather, she was unable to get off the farm. (13) While there, they adopted their son Bill. She recalls that he was an adventuresome toddler, and the neighbours were frequently bringing him home when he would wander off. They set up another pony club in Whakatane and Dudley also helped to set one up in Rotorua. (10)

Adah was a strong supporter of the SPCA and did not like to see animals suffer or be in pain. She started a branch in Whakatane and said this led to her doing almost as much veterinary work as medical. (10, 13)

Dudley passed away on 26 May 1976 at the age of fifty-two. (39) Their marriage lasted, at the most ten years.

Later Career

Circa 1956 they left Whakatane, as Dudley decided he didn’t like living there, (10) and moved to the town of Maraetai, the easternmost suburb of Auckland. (41) They lived in a house on Rewa Road owned by Dudley’s aunt and Adah set up her medical practice on the premises. She was the sole GP in Maraetai for the next twenty years until two other GPs came to the town. She recalls having to buy the house from his aunt as her husband was unkind to the aunt. (10) The 1960 Medical Practitioner Gazette indicates she had reverted to her maiden name so it is probable they had divorced by this time. (42) She continued her practice in Maraetai for at least the next thirty years. (10)

Her initial practice covered the area from Kawakawa Bay, to Maraetai, Beachlands, Whitford, and Clevedon but in 1962 a second surgery was opened at Beachlands cutting down the number of home visits she had to make. The 1992 Medical Practitioner Gazette indicates that at the age of eighty-eight she was continuing to keep her medical registration active. (43)

Adah’s initial Maraetai practice was in her home. Patients waited in the kitchen, and she saw them in the living-room. Later, the washhouse and garage were converted into a surgery. In 1957, a Mrs. Ivy Fitzgerald and her son came to live with Dr Adah and her son Bill. She was a nurse who had been living in the village since 1952 and had often looked after the locals’ medical needs when the Howick doctors could not attend. She answered the phone and cooked the meals for Adah and Bill. She always made enough for six as Adah often brought patients home for a meal. During her rounds (sometimes on horseback) Adah would see that some of her patients needed meals so she started providing “meals on wheels” – Mrs. Fitzgerald cooked these until the need became too great and the service was taken over by the Red Cross. The patients were never charged for these meals. (44)

In her oral interview, Adah’s strong interest in holistic and alternative health practices was evident. It is unclear how she used these in her own medical practice, but she personally had used chelation therapy in her early eighties and believed this treatment had caused her hair to change from white back to its original color, lumps on her body to fade away, as well as making her bones firmer and stronger. She used articulation treatment for hip pain and was confident she would not require artificial hips. She believed older people often died during surgery and chelation therapy was a much safer treatment for them. (10) In her obituary, her son Bill, recorded “Adah was a pioneer of alternative medicine, always questioning the establishment and urging people to think outside the square in all aspects of life, whether it was to look after people in need, nutrition, care for the environment or animals”. (45)

Other Interests

Adah had a strong medical heritage being the first second generation woman doctor in the country. She took an active part in the New Zealand Women’s Medical Association and in 1971 at the age of sixty-seven was given honorary membership. (46) She was also a honorary medical officer of the Auckland Residential Nursery Society. (47)

Her lifelong interest in horses has already been mentioned. She was keen to pass on her knowledge and to teach the local children to ride. (10) She set up a pony club in Maraetai in 1958 and later a second one in Beachlands. She purchased ponies, leased fields for their grazing, and most of the time paid for the shoeing of the ponies. The extent of her generosity to the local children is recorded in the 1992 interview for the Horse & Pony Personality of the Month. (13)

She enjoyed travelling – especially to the United Kingdom. She appears to have had a good relationship with her brother John who lived all his adult life there and endeavored to travel to see him on a regular basis. In his book, he had a picture of the two of them dressed up in their finery to go to the royal garden party given for colonials in the summer of 1936. (1)

She enjoyed driving and in her interview she mentioned her big Citroen car which she drove to house calls in the “utmost districts” during her Whakatane career days. (10) In her obituary, written by her son Bill, he comments that she was well known for her “breakneck speed” in her car as she went on house calls. (45)

She loved nature and enjoyed the bush reserve behind her home. In her oral interview, she mentioned it had an ionization crack which produced negative air ions which were very good for one’s health – “it gave you a lovely feeling which allowed you to get your mind in order”. (10) Today, Maraetai has the Dr Adah Platts-Mills Reserve, which is an 11.3 hectare broadleaf/kanuka forest with many native tree varieties, and forms part of the Maraetai Loop Walk – a ninety minute walk through both bush and shoreline and is located at 209 Maraetai Drive. (48)

In 1977, Adah received a Queen’s silver jubilee medal (commemorating the 25th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s accession in 1952) for her services to the Red Cross. (49) Her obituary indicates she established St Johns and Red Cross in the Maraetai area. (45)

Adah passed away in 2000 at the age of ninety-five. (10) She left behind her son Bill, his wife Helen and three grandchildren Katie, Gareth, and Grace. Her friend John Scott, said her son Bill, who passed away 26 May 2012, was a very respected bricklayer in the Maraetai area and was very community minded – no doubt influenced by his mother. In “The Magic of Maraetai : History of Maraetai School and District” published in 1981 to celebrate the centennial of the school several pen portraits are written including one of Dr Adah by a form two student Beverley Kempthorne. Her concluding paragraph sums up how the community viewed Adah. (4)

Doctor Platts-Mills is a very understanding and tolerant person. She is a much respected and greatly loved woman and it is an honour to have such a wonderful person in our community.

Bibliography

- Platts-Mills J. Muck, Silk and Socialism : Recollections of a Left-Wing Queen’s Counsel. Paper Publishing; 2001.

- Births, Deaths & Marriages Online Wellington: New Zealand Government – Internal Affairs; [08.08.2022]. Available from: https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz/

- E W Mills and Company Ltd Wellington: National Library of New Zealand; [05.08.2022]. Available from: https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22373492

- Obituary Mr. J. F. W. Mills. Evening Post. 1944 08.02.1944. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19440208.2.64

- Page D. ‘Platts-Mills, Daisy Elizabeth’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography: Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; 1996 [01.08.2022]. Available from: https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3p29/platts-mills-daisy-elizabeth

- Funeral of the late Rev. F. C. Platts. Otago Witness. 1900 07.06.1900. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OW19000607.2.58

- My Heritage [12.08.2022]. Available from: https://www.myheritage.com/research

- Page D. Dissecting a Community: Women Medical Students at the University of Otago, 1891-1924. In: Brookes B, Page D, editors. Communities of Women – Historical Perspectives 1ed. Dunedin: University of Otago Press; 2002.

- Hughes B. Three Karori Women. The Stockade. 1999(32).

- Platts-Mills DA. Interview with Dr Adah Platts-Mills , part of the New Zealand Medical Women’s Association: Records / Oral histories of NZ Medical Women Graduates. In: Glasgow N, editor. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs 1987.

- Music Examinations Dominion. 1917 04.08.1917. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DOM19170804.2.49

- Social and Personal. Dominion. 1915 11.06.1915. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DOM19150611.2.4.1

- Price J. Dr. Ada – Fairy Godmother. Horse and Pony. 1992(July ).

- Manawatu Show. Evening Post. 1917 02.11.1917. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19171102.2.10

- The Manawatu Show. Rangitikei Advocate. 1917 01.11.1917. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19220118.2.129

- Witmore M. Nga Tawa – A Centennial History. Waikanae: The Heritage Press; 1991.

- Matriculation. New Zealand Times. 1923 18.01.1923. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZTIM19230118.2.12

- Medical and Dental. Evening Post. 1925 23.12.1925. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19251223.2.79

- University of New Zealand. Otago Daily Times. 1927 10.12.1927. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19271210.2.3

- University Tests. New Zealand Herald. 1928 13.12.1928. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19281213.2.142

- University Honours. Evening Post. 1931 20.01.1931. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19310120.2.20

- Capping Ceremony. Evening Star. 1931 16.07.1930. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD19310716.2.87

- Dr. Adah Platts-Mills. Evening Post. 1933 06.02.1933. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19330206.2.40.8

- Wellington House Surgeons Resent “Living-In” Cut. Horowhenua Chronicle. 1931 01.05.1931. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HC19310501.2.11

- Personal Notes. Evening Post. 1933 06.02.1933. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19330206.2.165

- A Woman Doctor. Evening Post. 1934 23.03.1934. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19340323.2.153.14

- Social News. New Zealand Herald. 1934 17.05.1934. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19340517.2.7.1

- Personal Manawatu Times. 1936 26.11.1936. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19361126.2.101.6

- Personal. Manawatu Times. 1936 25.11.1936. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19361125.2.106

- Defects In Diet Manawatu Standard. 1937 10.12.1937. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19371210.2.136

- Advertisements Column. Manawatu Standard. 1937 15.12.1937. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19371215.2.227.2

- Advertisements. Manawatu Herald. 1939 22.03.1930. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MH19390322.2.19.3

- Lessons in Bandaging. Manawatu Standard. 1939 13.12.1939.

- Red Cross Society. Manawatu Standard. 1939 14.12.1939. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19391214.2.85.2

- St John Ambulance. Manawatu Standard. 1940 31.01.1940. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19400131.2.123

- Obituary. Evening Post. 1944 08.02.1944. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19440208.2.64

- Advertisements Column. Auckland Star. 1944 22.04.1944. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19440422.2.95.4

- The New Zealand Gazette Register of Medical Practitoners Wellington 1950 [04.11.2022]. Available from: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/other/nz_gazette/1950/22.pdf

- Charles Dudley Blomfield Auckland: Auckland Museum Online Cenotaph; [04.11.2022]. Available from: https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph/record/91316

- Supplement to The New Zealand Gazette 1951 Register of Medical Practitioners Wellington 1951 [04.11.2022]. Available from: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/other/nz_gazette/1951/81.pdf

- Supplement to The New Zealand Gazette Medical Register 1957 Wellington 1957 [07.11.2022]. Available from: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/other/nz_gazette/1957/75.pdf

- Supplement to The New Zealand Gazette Medical Register 1960 Wellington 1961 [04.11.2022]. Available from: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/other/nz_gazette/1961/4.pdf

- Supplement to The New Zealand Gazette Medical Register 1992 Wellington 1992 [07.11.2022]. Available from: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/other/nz_gazette/1992/184.pdf

- The magic of Maraetai : History of Maraetai School and District. Stone R, editor. New Plymouth: Taranaki Newspapers Ltd; 1981.

- Mills B. Maraetai doctor will be long remembered by local residents. Pohutukawa Coast Times. 2000.

- Maxwell MD. Women Doctors in New Zealand- An Historical Perspective 1921-1986. Auckland: IMS (N.Z.) Limited; 1990.

- Residential Nursery Society Care of Children. Auckland Star. 1945 26.10.1945. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19451026.2.108

- Maraetai Loop Coastal Walk Auckland Walks In Auckland; 2015 [updated 05.03.201507.11.2022]. Available from: https://walksinauckland.com/tag/dr-adah-platts-mills-reserve/

- Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal 1977 Auckland: Honours Unit, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.; 2022.