This biography is largely based on an oral interview with Tania’s son Professor Alistair Gunn and her daughter-in-law Dr Diana Rabone conducted in October 2022 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. Anecdotes of colleagues who worked with Tania have been contributed by her granddaughter Dr Eleanor Gunn. The interviewer was Prof Cindy Farquhar and the biography was constructed by Rennae Taylor. Other sources are listed in the bibliography.

This biography is largely based on an oral interview with Tania’s son Professor Alistair Gunn and her daughter-in-law Dr Diana Rabone conducted in October 2022 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. Anecdotes of colleagues who worked with Tania have been contributed by her granddaughter Dr Eleanor Gunn. The interviewer was Prof Cindy Farquhar and the biography was constructed by Rennae Taylor. Other sources are listed in the bibliography.

Class of 1955

Contents

Family Background

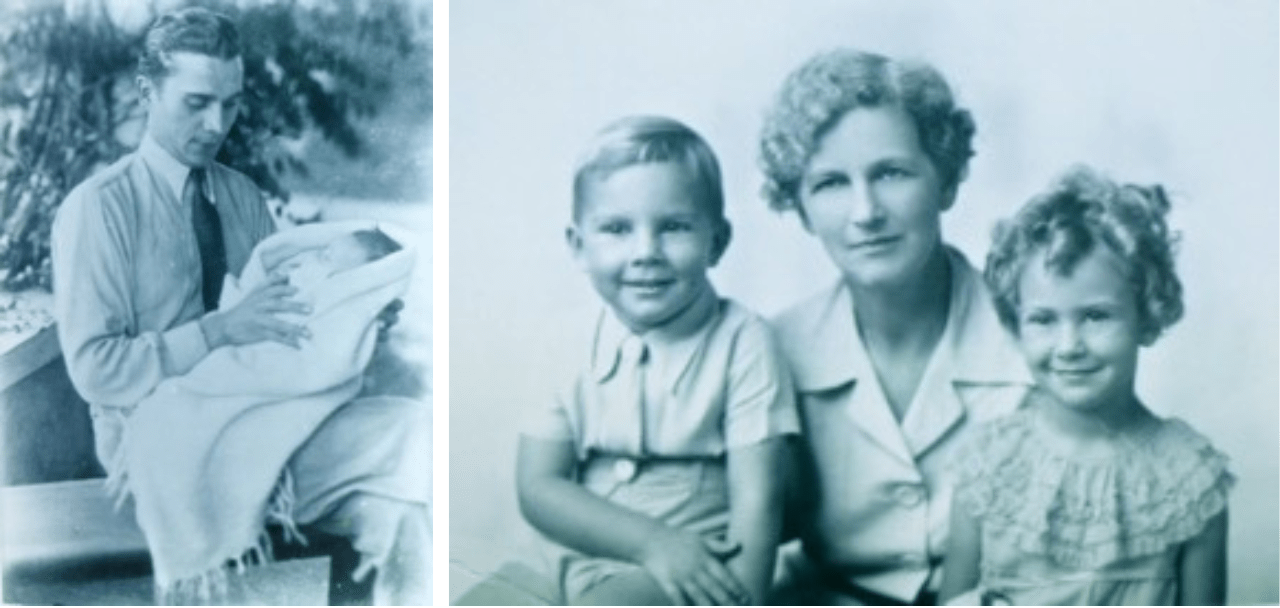

Tatiana (Tania) Roberta Tarulevicz was born in Hamilton on 23 August 1932 to Jan Gera and Evelyn Marie Ethel (nee Scherer) Tarulevicz. Her only sibling Ivan was born the following year. (1)

Tania’s mother, Evelyn, was born in Midhurst in the Taranaki (about four kilometers north of Stratford) in 1895. Her background was German, Swiss, and Lithuanian. (2)

Evelyn’s mother, Friederike Gernhoefer, immigrated as an eight-year-old with her German family in 1875. The Gernhoefers had lived in Kaliningrad, (previously called Königsberg) in East Prussia and had married Lithuanian women so they were a combination of Germanic and Slavic stock. Tanya’s maternal grandfather was the patriarch of this family and had decided the family needed to leave Germany because of Bismarck’s mobilization of the German army. He was a strict Methodist and pacifist and believed that killing people would damn his soul. He believed if he stayed in Prussia he would be conscripted into the army, which would lead to being either executed or killed. Circa 1875, he literally went around the world, came back and told the family that he had booked tickets to New Zealand for the whole family, and they were leaving in three weeks. They bought land in the Stratford region of Taranaki and after clearing the bush land and constructing houses they settled into a farming lifestyle.

Evelyn’s father, Alphonse Bernard Scherer, born in 1862, was of Swiss origin and as a fourteen-year-old boy had also immigrated in 1875 with his family. They also had bought bushland in the Stratford area and, after clearing the land, commenced farming.

Friederike Gernhoefer married Alphonse Bernard Scherer sometime in 1885, worked hard and eventually saved enough to buy a larger piece of farmland. In 1901 they sailed from New Plymouth to the Manukau Harbour with their farm animals and then travelled overland to their 1000-acre block of land in the Waharoa, Waikato region. Years of work on this land which was initially covered in scrub, gorse and mud resulted into several lush dairy farms. They had eleven children, nine of whom reached adulthood; Evelyn was their seventh child.

Evelyn enjoyed caring for the farm animals but when her pet calf was butchered, she vowed never to eat meat again and remained a vegetarian until the end of her life. She attended Hamilton High School for two years and then at the age of fifteen was employed as an assistant to a Hamilton photographer where she learned the art and business of photography. When he died, she bought the business and worked as a photographer for the next sixty years until the age of seventy-six.

Evelyn was a financially independent young woman. She bought her own car in 1921 which allowed her to go further afield with her friends. She enjoyed tramping, sailing down the Wanganui River, and skiing on Mount Ruapehu. In 1931, she put a manager in charge of her business, and she and her younger sister went travelling in England and Europe.

Much less is known about the history of Tania’s father, and what is known is considered unreliable by members of the family. Jan Gera Tarulevicz claimed to be of “aristocratic Russian stock and a White Russian” who had fled from Russia to the United States following the revolution. When Evelyn met him, he was an American journalist travelling on a fake Polish passport and possibly working for the CIA as a spy. The family think he was born in Russia, but have never been able to confirm this. (2) Certainly some anecdotes support an aristocratic background, and he had a fierce hatred of the Bolsheviks.

Evelyn met Jan in Moscow and after a whirlwind romance they were married in London. They returned to New Zealand where they had two children, Tania in August 1932 and Ivan in 1933. Jan was unable to get New Zealand citizenship and had to leave New Zealand. In 1938 the family spent several months together in Indonesia and plans were put in place to settle in the United States but World War II broke out and visas were unobtainable. (2)

Her grandson Alistair’s recollection from family stories were:

She met this mysterious, dashing stranger in Moscow, and married him. He was not allowed to live in New Zealand because of the immigration regulations. So, they met here and there around the world. He fathered two children. She raised them working solo as a photographer, running her own photography studio in Hamilton and in the context of a strictly Methodist family who clearly found her arrangement somewhat irregular. But we’ve seen the wedding and marriage certificates etc,… But he was constantly trying to arrange for them to join up, but then the war came, and she got notified by the United States department that he had gone missing. There was some evidence that in fact he did survive the war and thus abandoned his family. We cannot confirm any of this. Multiple letters have been written, but when one’s dealing with that notoriously closed-mouth branch of US government….

All contact between Evelyn and Jan was lost during World War II. Alistair and Diana say Tania never talked about her father.

Childhood

Tania and her brother Ivan were raised by their mother in Hamilton. While Evelyn’s parents were alive, she and the children lived in the big family home by the Waikato River. She was effectively a solo mother, married but living separately. She supported herself and her two children with her own successful photography business. Like some of her forbears who had immigrated to New Zealand, she was a strict Methodist, very straight-laced and firmly spoken. Diana’s memories of her were from around 1983, just prior to her death in 1984. She was living with Tania and was a “very grouchy old woman who didn’t like the look of me one bit”.

Evelyn was determined for her children to be successful. The following story indicates the strength of their mother’s character:

She taught the children to swim by swimming across the Waikato River at the Cobham Bridge – back and forth – with a child on each side of her holding on to a strap of her bathing suit as needed. And this was when they were probably of about six and eight years of age.

Tania attended the Waikato Diocesan School for Girls where she was awarded the I.B. (1940) and II.A. (1942) form prizes at the end of year break-up. Evelyn offered Tania the opportunity of going to a private school for her secondary schooling as she believed she would make contacts there which would be of great value to her. Tanya replied “Mummy, the public school in fact has a better reputation in science and I intend [on] having a career which will depend on that. Therefore, I am going to the public school”. So, Tania went to Hamilton Girls’ High School. She considered her secondary education in chemistry and biology was good but physics not so much. Family members are not sure if Tania had to go to the Boys’ High School for her physics education.

She and her brother learned to ski, had vacations by the seaside, and their mother spent money on travel. Christmas and birthday gifts consisted of books which were exchanged and discussed. Tania learned to play both the piano and violin to Grade Eight level. Many years later, Diana wondered why she never played music in the home and asked her.

You were very musical, and obviously you weren’t able to keep that up, but you don’t listen to music? What is that about?” And she said, “I don’t play music at home because it stops me thinking.” Very practical.

When asked where the drive to apply for medical school came from, Alistair believes she always wanted to be a doctor and planned her career goals before she entered high school. He is unaware of any very early role models which influenced her. She worked hard and as far as they are aware she had no problems enrolling into medical school.

Her brother Ivan, now deceased, studied at the University of Auckland School of Architecture and became “the most famous student never to graduate” – they held a wake for him when he died and now house a collection of his works in their archives. (3) He was a good friend of Hundertwasser and was instrumental in the concept and delivery of the Southern Hemisphere’s first geodesic dome. He was also involved with New Zealand’s first sustainable housing including grass roof homes. (4) Unlike Tania, he was very flamboyant in character, enjoying fast cars, fast downhill skiing, drinking, and socialising. He died in his fifties in Spain of an episode of acute pancreatitis. He had suffered from recurrent bouts of pancreatitis since a skiing accident when his spleen had to be removed. Tania felt his loss keenly.

Medical Education, Early Post-Graduate Training, Marriage and Babies

At the age of twenty-three years, Tania successfully completed her sixth year of medical school and was awarded her M.B. Ch.B. at the end of 1955. Family believe she stayed in St Margaret’s College during her first year in 1949 and then went into a flat with other girls. She travelled down to Dunedin from Hamilton by train and by ferry. One amusing story Alistair remembered indicated her naivety on that first trip.

She spent the train trip playing cards with guys she met on the train and tells it as an averted disaster because she thought they were playing for points on the whole train trip. At the end of it, one of the guys she was playing with got up and counted out the best part of £100 and handed it to her. That was an awful lot of money. She hadn’t realized she was good at cards, and she thought she was just playing for points. She was very conservative and had no idea she was putting herself at risk.

Tania did not have any financial difficulties during her medical training; they believe she would have obtained a bursary to assist with costs with some assistance from her mother. She was diligent in her studies but also participated in university life. She was the 1953 – 54 vice-president of the Otago University Students Association and she joined the Alpine Climbing Club where she met her future husband Bernard (Bernie) Gunn.

Bernie was born in Wanaka in 1926. After high school, he worked for two years in the forestry service, so was a couple of years older than most freshman university students. The forestry service at that time had a scheme where you could attend university once you had served two years. Alistair believes Bernie was the only person who ever graduated from the scheme, with an MSc in Geology. During university breaks, he worked each summer at Mount Cook as a semi-professional climber and guide.

In 1956, Tania was a junior house surgeon at Dunedin Hospital and in 1957, a Senior House Surgeon at Waikato Hospital. She and Bernie married in 1957 and they had their first child, Alistair in 1958. Tania’s intention upon graduation was to specialize in geriatrics and during 1960 – 1961 she worked as a medical registrar at Dunedin Hospital. They had their second son, Derek, in 1962.

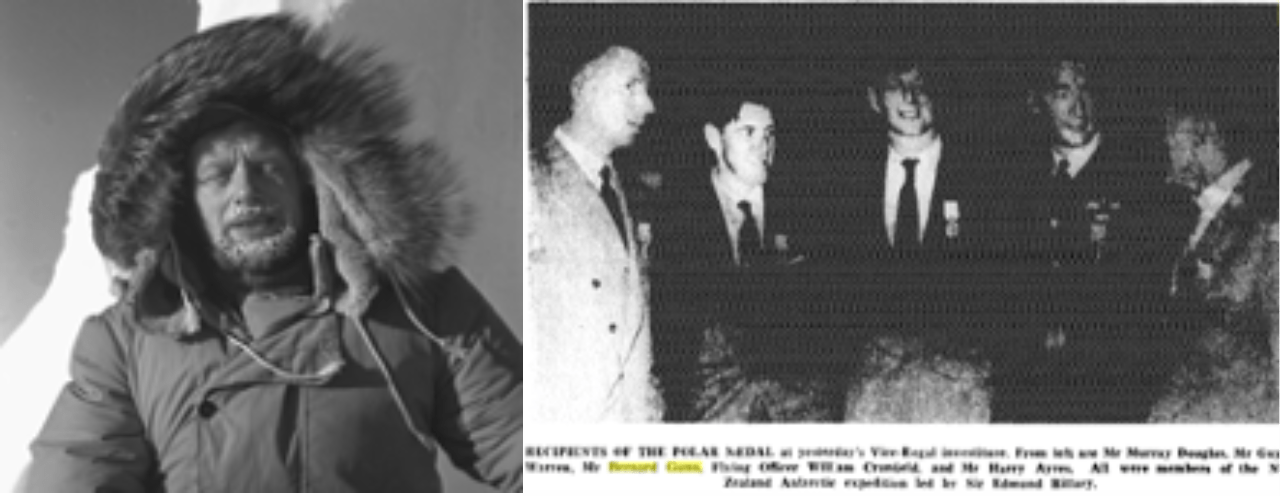

Bernie was a junior geologist on the 1957 – 58 Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (TAE) and International Geophysical Year (IGY). Sir Edmund Hilary was enlisted to lead the New Zealand team that would lay supply depots from the Ross Sea towards the South Pole for the first trans-Antarctic crossing by Fuchs and his team. In a little more than a year on the ice, Hillary’s TAE/IGY party established Scott Base, supported Fuchs and explored and mapped considerable areas of the Ross Sea region and the Transantarctic Mountains, laying the foundations for the more detailed mapping and geology that was to follow. (5) Helped by his alpine background, Bernie did his PhD on the Volcanics of Antarctica. He was also part of the team which did several first climbs of major mountains in these ranges where he spent time mapping, climbing and collecting samples. Mount Gunn is named in his honour.(6) He was one of the members of the Antarctica expedition who received the Polar Medal in November 1958.(7)

Bernie returned to do further work in Antarctica during the summer season of 1959 and was involved with two others in a serious accident – their snowcat fell into an undetected crevasse. The driver was killed and the other two were not found until twenty hours later. They were flown by helicopter to the ship Super Constellation which brought them back to New Zealand.(8) Due to Tania’s intervention, they were able to preserve most of Bernie’s toes despite significant frostbite.

Bernie returned to do further work in Antarctica during the summer season of 1959 and was involved with two others in a serious accident – their snowcat fell into an undetected crevasse. The driver was killed and the other two were not found until twenty hours later. They were flown by helicopter to the ship Super Constellation which brought them back to New Zealand.(8) Due to Tania’s intervention, they were able to preserve most of Bernie’s toes despite significant frostbite.

The Years of Travelling

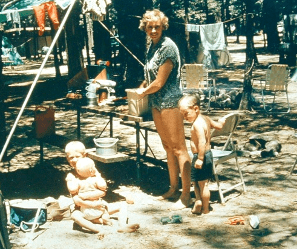

In 1963, Bernie went to Canberra on a postdoctoral geology fellowship and Tania and the two boys, now two and four years of age, accompanied her to Niue where she enjoyed her year as the medical director of the Niue Island Hospital. She had home and childcare help to assist her with the little boys. Alistair’s only memories of this time are of walking down the main street and being interested in the palm trees blowing in the wind. Tania always recalled this as a very happy time.

Tania and the two boys then joined Bernie in Canberra where Alistair’s schooling commenced and Christopher, their third son joined the family in 1964. During 1964 – 1965 Tania did after hours work in the Emergency Department of Canberra Community Hospital.

Bernie was then offered a position in the Geology Department of Tulane University of Louisiana; they were told it was a conservative university but had a solid science programme. However, they realized on their arrival circa 1965 it had a very strong medical programme but the Geology programme was just getting established. One of the first tasks he was asked to do was to review the thesis of their first PhD graduate. Alistair recounts the story of getting to Montreal, Quebec via Tulane:

They asked him to review the thesis of this person and said, “Hey, it’s our first graduate, and it should be fantastic.” And he read it, and it was all about the geology of Louisiana Basin which of course is soft rocks and sediment, rather than his specialist field of volcanoes ….. He read it. He had this terrible feeling of familiarity, and he thought, “I’m sure I’ve read this before.” And he went to the library and pulled out the biggest traditional volume, and there was chapter one. There was chapter two, and there was chapter four.

He went back to the people, and said, “I can’t review this. It’s on soft rocks. What you need is a real sediment man.” He had already arranged the reviewer, and of course, it was the author of the textbook. You can imagine what his reaction was.

From Tanya’s point of view, she had enjoyed work in Australia. She intended to do casual work until we were old enough to go into childcare, and then she would restart training. But of course, moving to the States was a huge step, and she decided no, she couldn’t really do it. She wasn’t willing to re-license there. So, she stopped practicing medicine when they moved to Louisiana. After two years in Louisiana, they realised just how corrupt the State was in most blatant ways, how objectionable the social situation was. I could tell stories about that too.

And when he looked for other jobs, he got a job in Montreal, so they drove all the way to Montreal from Louisiana going up the West Coast and across, arrived, discovered that– you went down the Trans-Canada Highway and at the Quebec border it turned into a two lane, wiggly road.

The previous provincial party Union Nationale had been in power in Quebec continuously since 1944 and had refused to either borrow money to invest or to support higher education beyond the basic two-year liberal arts university degree, which means law, theology, and history, and that’s it. There were no other degrees. The provincial Liberal Party got into power in 1960 and was like, “Right, this is ridiculous. We need a proper university system,” and tried to develop a science programme, which is why they hired people from outside of Quebec.

Settling in Montreal

The Gunn family settled into their new city for approximately the next ten years.

In 1966, Alistair recounts the fourth addition to their family:

So in Canada, they adopted a girl. So child number four, Diana, is adopted. Tania’s reasons were because she had three great lumps of sons and thought, “Well, what are the odds if I have a fourth child, that this would be yet another great lump?” So they adopted a six month old little girl of French Canadian and Indian ancestry. And when Diana was four, she just said, “Right, as agreed, I’m retraining.”

The Canadian system, unlike the American system, recognized Tania’s medical degree but not her post-degree training so she did a full general rotating internship at the Jewish General Hospital before embarking on her post-graduate studies at the Montreal Children’s Hospital.

Tania thought since she had four children and had closely observed child development it would be easy to retrain in paediatrics. She also felt that the long-term outcomes for children were ultimately much better than her original goal of geriatrics. She commenced her training as a Paediatric Resident in 1972. She became Chief Medical Resident at the Montreal Children’s Hospital in 1973 and during 1974 – 1975 was a Neonatology Fellow, also at the Montreal Children’s Hospital. In 1975, she became a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Paediatrics and was also successful in gaining her American Board of Paediatrics in 1976 and her American Sub Board of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine in 1977.

During 1976 – 1977, she was a Lecturer in the Department of Pediatrics, McGill University, Montreal as well as Acting Director of the Neonatal Follow-Up Clinic at the Montreal Children’s Hospital.

Return to New Zealand

Their time in Canada came to an end when Bernie quarreled with his employer, the L’Université de Montréal, over language. Alistair recounts his recollection of this time:

He was teaching in English. Now, it’s interesting. He said to all the undergraduates in geology, “Look, I will mark essays in any European language you choose. I can read French. I can read German. I can read Portuguese. I can read Spanish. Hand it over. But if you want a job in North America– everywhere but Quebec works in English, therefore I’m going to teach you in English.” Eventually, it came to a crunch where they said, “Okay, you must pass a French language exam.” Now, the fact is, he could have passed it for two reasons. First, he was actually good at languages, and had very good French vocabulary and was better at the language than I was. And I went to high school in French. Secondly, they weren’t stupid enough to put any of his internal enemies on the board. Instead, they put several of his close French-speaking colleagues, one of whom was a Belgian native French-speaker on the board.

It is impossible to know how things would have turned. Tania and I thought that in the circumstances they would’ve passed him if he had said, “Bonjour.” However, at that point, he was angry with the university, went on sabbatical, sailed off down the St Lawrence River in his 50-foot ferro-cement ketch, which he had built on the banks of the St Lawrence River. We stopped in Puerto Rico for 6 months, where he completed a research collaboration and publication with a colleague on the volcanic islands of the West Indies. After that though, he just kept on sailing until he got back to New Zealand accompanied by his two older sons. He resigned at the end of the sabbatical year.

Tania sensibly felt it was unwise to just turn up in New Zealand and ask for a job; it would have been better to apply while employed overseas but Bernie refused to take her advice. However, she took her own advice and completed her postdoctoral training with her mentors, one of whom was Professor Jacob Aranda who received the Landmark award in 2022. In an email from Professor Aranda to Alistair he writes:

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has chosen the first pioneering work on Caffeine Citrate which included three fellows/staff at McGill including your mom to be the recipient of the AAP Neonatal Landmark Award – “This award recognizes an individual contribution that has substantially changed the practice of neonatology with a publication that has stood the test of time (at least 15 years since publication). The use of caffeine to treat apnea of prematurity has impacted countless newborns and is indelibly imprinted on the daily work of every member of our neonatology community.”

It will be a great honor to accept this Landmark Award in behalf of your mom, Winnifred and Hordur on Saturday 8 October 2022 in California.

Tania completed her studies on caffeine which showed that it significantly decreased the need for and the duration of mechanical ventilation in low birthweight babies who had neonatal apnea. She published this research entitled “Sequelae of caffeine treatment in preterm infants with apnea” in the Journal of Pediatrics in 1979.(9) She also completed work on risk factors in retrolental fibroplasia (10) and published a letter in the prestigious Lancet journal on the incidence of this condition.(11)

She then applied for positions back in New Zealand. To her disappointment, she was unsuccessful in her application for the academic position at National Women’s Hospital but was successful in her application to St Helen’s Hospital, Auckland.

St Helen’s Hospital, Auckland

From 1978 – 1989 Tania became one of St Helen’s two specialists in neonatal paediatrics. It was a Level 2 neonatal unit. Although it was not her preferred position in which to continue research work, she made it work despite doing the solo on-call duties seven months of the year.

In addition to her work at St Helen’s, she also became an honorary senior lecturer in the Department of Paediatrics at the University of Auckland from 1979 – 1989.

Alistair’s wife, Dr Diana Rabone, remembers her early relationship with Tania, which demonstrates her perception of people:

I was bit older. I’d done a degree before I went into medicine. And also I’d been out doing general practice locums after I’d bailed out halfway through my second houseman year. These locums acted as a form of apprenticeship but then decided I also needed the Diploma in Obstetrics. I started at St Helens on SCBU (special care baby unit) where Tania was the senior doctor. I remember the very first ward rounds we did …. there was a group of about six of us, and she was doing rounds showing us all these babies, and she just quietly asked, “Now this baby’s having magnesium supplementation. Could anybody tell me why that is?” And none of us could. So anyway, I went home, looked it up of course, and the next ward round she said, “Can anyone tell me about magnesium?” And I was the only one who’d gone and looked it up, so she sort of noticed me more after that. And also, there was only 20 years’ difference, well, only.

That was her trademark …. she would sort of notice people and ask them questions and keep track of what they answered.

She set little tests and she would never make any overt judgement, but she was certainly making judgements all the time. And this had a very good spinoff for me because of course we did the first half of the diploma at St Helen’s, and then we shifted over to National Women’s. And quite by chance, close to the end of the year, I met her in the corridor and she said, “Oh, I remember you. Diana isn’t it?” And then impulsively asked me to their end-of-year barbecue that they always put on at their house for the registrars, (although I was not a registrar, I was a senior house officer) so I turned up to this and met the family and sort of became a friend.

A year or so later, I was going down to the South Island for a tramping holiday, and I was going to be coming back about the same time Alistair was coming back from Wellington – he was working at Wellington Hospital. And somehow without cellphones and such, well, she said, “Oh, how about you sort out and stop by and meet up with Alistair and drive him home, because otherwise he’ll try and bicycle home, and this worries me.” She was always worried about him bicycling home.

Anyway, I don’t know how we managed to rendezvous on the steps of Wellington Hospital, but he got in the car and we drove north. We got to know each other quite well on the drive back from Wellington. So that was our first meeting, basically. So Tania introduced us and gave us little nudges along the way.

Research Work During the St Helen’s Era

Despite minimal research funding and being in a Level 2 neonatal unit, Tania developed research collaborations back in Auckland with a range of other researchers. In reviewing her publications in a Medline search during this time from 1978 to 1990, some of her co-authors included:

- Professor Gordon G. Power, professor of fetal physiology at Loma Linda University, CA, USA. He visited Auckland on sabbatical several times and was critical in the ‘birth in utero’ studies that Tania did for her MD. A gentleman and a very rigorous researcher in physiology according to Alistair.

- Dr P.M. Mok, consultant radiologist, who collaborated with imaging aspects of fetal abnormalities

- Dr J.D. Mora, consultant radiologist, who collaborated with imaging aspects of SIDS research (before it was called SUDI)

- Mr Percy Pease, paediatric surgeon at St Mary’s Children’s Hospital, who collaborated on fetal diagnosis with imaging of upper urinary tract dilatation and outcomes

- Dr Barbara Johnston, fetal physiologist who worked with Professors Power and Gluckman

- Dr Graeme Woodfield, a haemotologist, who worked with her on the hepatitis B studies

- Professor Peter Gluckman, paediatrician and biomedical scientist who now holds a Distinguished University Professorship at the Liggins Institute of the University of Auckland, who supervised her MD

- Professor D.M. Becroft, perinatal pathologist, who collaborated on intracranial and subdural haemorrhages

- Ann Nightingale, last matron of St Helen’s Hospital, collaborated on quality outcomes and costings in the neonatal service

- Dr Shirley Tonkin, paediatrician and sudden infant death syndrome researcher; as well as research collaborations she and Tania were also good friends. Tania said they combined the best of Celtic imagination and Teutonic organization.

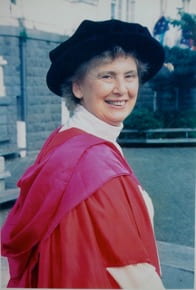

In 1989, she was awarded her Doctor of Medicine, Paediatrics, from the University of Auckland. Her thesis was entitled “Responses of the fetal lamb to alternations of the thermal environment in utero”. It showed that while many of the thermoregulatory responses to cooling are present in utero, nonshivering thermogenesis does not occur until the fetus is oxygenated and the umbilical cord is occluded. Her subsequent studies dissected the multiple factors preventing thermogenesis before birth, including inhibitors secreted by the placenta, and adenosine. It showed that cooling the cutaneous thermoreceptors stimulated fetal breathing, with coordinated activity of upper and lower airway muscles. Her supervisors were Professors Gluckman (primary) and Power. She received some research funding from the Health Research Council (HRC) and the Auckland Medical Research Foundation (AMRF) for this work.

National Women’s Hospital

In mid-1990, St Helen’s Hospital closed, and Tania became a whole-time specialist in neonatal paediatrics at National Women’s Hospital where she was employed until her retirement in 1997 – when she turned sixty-five. However, she continued to do locum work at National Women’s following her retirement. She thoroughly enjoyed the camaraderie with her colleagues and the stimulation of working in a Level 3 neonatal unit. She became involved in teaching at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels. During the 1990s she was successful in getting further funding from the Lottery Board, HRC, and AMRF for a larger study. Her 1996 PhD student, Trecia Wouldes, is now a professor and head of the Department of Psychological Medicine at the University of Auckland.

In 1990, she became an honorary associate professor and in 1999 was made an honorary professor in the Department of Paediatrics at the University of Auckland.

The next step was somewhat unexpected. Tania had taught her son well when it came to never letting a baby become cold because of the risk of hypoglycemia, coagulopathy, and pulmonary hypertension. When he found in a preliminary study that an experimental anti-epileptic drug improved brain outcomes but had a high mortality and made the baby rats cold, he decided to repeat the same study but keeping the rat pups warm – he thought the outcomes would be even better. In fact, if the rats were kept warm there was no significant effect on brain injury. He decided that studying this “side effect” would be more interesting, since cooling alone seems to account for the benefit.

Alistair wanted to go straight to a large animal study to avoid the difficulty of controlling temperatures in small animals that needed to be kept in with their mum overnight. He approached Tania because of her experience of cooling in utero in the fetal sheep for the birth in utero study. It is fair to say that she was very enthusiastic, and her input was critical in developing a working protocol! Their animal research (12) was the first to show that mild delayed cooling of the brain after severe ischemic injury could dramatically reduce injury and improve recovery of brain function, provided that it was continued for at least 3 days, when secondary injury had resolved. This then led to a randomized safety study on the use of selective head cooling in newborn infants after perinatal asphyxia that unexpectedly for the time showed that mild induced hypothermia in infants with acute neonatal encephalopathy at birth was safe and tended to improve outcomes.(13)

Contribution to Her Profession and Community

Tania was very generous with her time and contributed in various ways to her profession. Some of these contributions during the 1980s and 1990s included:

- Chairing the St Helen’s Perinatal Mortality Committee.

- Treasurer and later chairman of the Paediatric Society of New Zealand, Auckland Branch.

- Secretary and later chairman of the Auckland Neonatal Group.

- Trustee of the Wilson-Sweet Research Foundation.

- Chairman of the medical advisory committee, NZ Cot Death Association as well as a board member of the association.

- Ad hoc referee on various granting bodies and international journals.

Untimely Death

In the summer of 1998 – 1999, Tania was feeling unwell and felt she needed a break, so she joined Bernie at their holiday home in Wanaka. Alistair recalls getting a phone call saying they had been on a road trip, and she was getting incredible backache, so she was flying home. He met her at the airport, and she was jaundiced and looked extremely unwell. She had been taking diclofenac and thought she had cholestatic jaundice. They immediately organized for her to have a CT scan and she was diagnosed with advanced cancer of the head of the pancreas. Her family, friends, and colleagues were in shock at the rapidness of her decline. She passed away on 29 March 1999 in her sixty-seventh year. Her funeral was held at St Mary’s Cathedral, Parnell – the church was full as an outpouring of tributes were given.

Her tombstone in Wanaka Cemetery records she was a Wife, Mother, Paediatrician, Scientist. Her husband Bernie, who passed away nine years later 16 March 2008, was described as a Husband, Father, Geologist, Explorer, Sailor, Aviator.

She has left a legacy in her children and grandchildren:

Alistair is a paediatric endocrinologist and professor in medical physiology at the University of Auckland and has continued to build on his and Tania’s earlier research. He and Diana have four children, their eldest, Eleanor, has followed in her grandmother Tania’s footsteps and is currently a senior pediatric registrar.

Tania’s second son, Derek, is an IT specialist and web page designer – he had two children with his late wife Katya. Christopher qualified in electrical engineering. Tania’s youngest, Diana, became a nurse and had two children with her late husband Geoff Coldham [Sadly, Tania never met these two grandchildren.] She took a strong interest in all her grandchildren and influenced their early lives.

Her granddaughter Eleanor remembers her well, reading to them, asking about schoolwork – “She expected us to be better and improve, but she knew how to get the best out of us. She made washing the dishes a fun game and when she found I didn’t know my times tables she was visibly disappointed, but then went away and wrote out the cards and said ‘Look, you need to know them, so I’ll pay you $5 for each one you learn!’ They were learned of course.”

She is still remembered after more than 20 years by colleagues. Her granddaughter Eleanor Gunn has worked as a NICU registrar both at Starship and at Middlemore. Her comments provide a fitting summation of a life of care and service.

At least once a week I will meet someone (midwives, nurses, paediatricians) who will say ‘Gunn, any relation to Tania?’ and then they share their stories.

The nurse specialists remember her tireless care and teaching and support. One nurse practitioner was a bedside nurse when they cooled the first baby (for the Head Cooling Trial) and said Tania did not leave the baby’s bedside for three days. Other stories focus with affection on her total lack of concern for appearances – there’s the time the nurses noticed she was limping; she eventually realised that she was wearing one high-heeled shoe and one flat! She had not noticed all ward round because she was so focused on the babies. Her trademark lace-ups were often one black and one brown. And there was the time she had a media interview on the ward that she had forgotten about and had to borrow a hairbrush urgently at the nurses’ insistence. Eleanor mentioned that one of the nurse practitioners had hugged her the previous week saying how lovely it was to work with her because she has so many of Tania’s mannerisms that ‘it’s just like working with Tania again.’ Eleanor says ‘At Auckland my impression is that the department is almost still expecting her to walk through the doors again at any moment.’

One aspect is clear from all the recollections: So many women feel that she took a personal interest in them and advanced their careers and really cared about them. The current NZ medical workforce is collectively very grateful to her.

Her son Alistair has many comments and anecdotes as well, of course.

She was self-confident but unassuming, and remarkably practical.

She also understood people’s motives. She wasn’t bemused by what was going on. She would have made an excellent politician. She was actually very good at reading people and in a very gentle way getting them to do what she wanted. But in a good way. So, for example she deliberately listened to the cricket radio in order to have things to talk about at work. She had the same interest in sport that I have, which is ‘I’m convinced that I have been gene deleted.’ But she deliberately paid attention to that in order to be able to, at morning tea, say, “Ah, the test yesterday was great,” I have never be able to make myself do this….. But that paying attention to what other people are interested in, was part of her character and helped oil the wheels.

She was very clever and is still sadly missed.

Bibliography

- Evelyn Marie Ethel Scherer: Family Search; 2019 [03.03.2023]. Available from: https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/KCDS-52T/evelyn-marie-ethel-scherer-1896-1984

- Gunn T. Evelyn Tarulevicz. The Book of New Zealand Women Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa. Macdonald C, Penfold M, Williams B, editors. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books Ltd; 1991.

- Manuscripts and Archives: Ivan Tarulevicz., MSS. Archives. Arch. 2017/1. File T196 Auckland: University of Auckland Librairies and Learning Services; 2017 [03.03.2023]. Available from: https://archives.library.auckland.ac.nz/repositories/3/archival_objects/147493

- Ivan Tarulevicz: Lost Property; [03.03.2023]. Available from: https://www.lostproperty.org.nz/odds-sods/ivan-tarulevicz/

- History of the TAE and the IGY – Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition And International Geophysical Year Christchurch: Antartic Heritage Trust; 2022 [03.03.2023]. Available from: https://nzaht.org/conserve/explorer-bases/hillarys-hut-scott-base/history-of-the-tae-and-the-igy/

- Mount Gunn: Wikipedia; 2022 [03.03.2023]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Gunn

- Recipients of the Polar Medal. 1958 13.11.1958. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19581113.2.110

- Rescue in the Antartica. Press. 1959 23.11.1959. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19591123.2.7

- TR G, K M, P R, D W, JV. A. Sequelae of caffeine treatment in preterm infants with apnea. Journal of Pediatrics. 1979;94(1):106-9.

- TR G, J E, EW O, JV. A. Risk factors in retrolental fibroplasia. Pediatrics. 1980;65(6):1096-100.

- TR G, JV A, J. L. Incidence of retrolental fibroplasia. [Letter]. Lancet. 1978;1(8057):216-7.

- AJ G, TR G, HH dH, CE W, PD. G. Dramatic neuronal rescue with prolonged selective head cooling after ischemia in fetal lambs. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;99(2):248-56.

- AJ G, PD G, TR. G. Selective head cooling in newborn infants after perinatal asphyxia: a safety study. Pediatrics. 1998;102(4 ):885-92.