This biography was written by Michaela Selway in 2021 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. Information on the sources used can be found in the Bibliography at the end of the biography.

1900 Graduate

Contents

A Lost History

In 1900, the third class of women medical students graduated from the Otago Medical School. This was the first class to contain more than one woman (Emily Siedeberg graduated alone in 1896 and Margaret Cruickshank graduated alone in 1897). One of the four women to graduate in this year was Constance Helen Frost.

Very little is known of Constance before her career began and even during her career, she was highly overlooked. Despite being within the first six women to obtain the degree of Medicine and Surgery from Otago Medical School, Kathleen Anderson argues that Constance’s entire life has been ‘ignored historically’ because she did not conform to the traditional role expected of women doctors: to care for women and children by becoming Pediatricians, Obstetricians, Gynaecologists, or General Practitioners [4, p.7]. Indeed, despite being the second woman doctor to obtain a position at Auckland Hospital, which lasted seventeen years, the official history of Auckland Hospital makes no mention of her [1, p.221].

—-

Constance Helen Frost was born in London, England in either 1862 or 1863 as one of ten children of Thomas Frost and Mary Ann (nee Antwis). The family moved to New Zealand around 1879, (when Constance was seventeen years old) and settled in Onehunga, where they lived for the majority of their lives [1, p.219; 2, p.32; 5]. All information about her life before her graduation is obtained from newspaper articles.

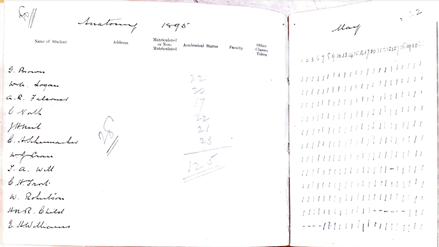

The first mention of Constance after the family’s move to Onehunga was in the Auckland Star in January 1884. This article announced Constance’s intention to study medicine ‘having studied at the Auckland Training College, [and having] passed the medical preliminary examinations’ [2, p.32]. In November 1890 and May 1891, the New Zealand Herald reported the classes Constance had passed during her university examinations at the Auckland Training College.

On 13 November 1891, the Auckland Star announced that Constance had passed Class II for German.

On 13 November 1891, the Auckland Star announced that Constance had passed Class II for German.

The next mention of Constance was in March 1895, where the Otago Daily Times reported the grades for the University Examinations. Constance received a Second Class for Materia Medica.

Following this, nothing of her is mentioned until her graduation from the Otago Medical School in 1900 alongside three other women: Daisy Platts-Mills (nee Platts), Alice Horsley (nee Woodward), and Jane Kinder [1, p.219; 2, p.32; 5]. Constance was 33 years old when she graduated.

“Specialising” in Pathology: Adelaide Hospital & Auckland Hospital

Early in 1900, an article in The Observer announced that Constance Helen Frost would be taking up a House Surgeon’s position at Auckland Hospital following her graduation. ‘Hospital positions for women medical graduates were almost non-existent in New Zealand’, so this appointment was quite an accomplishment [2, p.33]. Nevertheless, the position never eventuated. It is unknown what transpired, but Constance Frost was next heard of accepting a Resident Medical Physician’s position at Adelaide Hospital alongside fellow graduate, Jane Kinder. Alice Woodward took up the position at Auckland Hospital instead.

Constance and Jane were the only two women doctors at Adelaide Hospital at this time; they had applied at an opportune time to obtain their positions [1, p.220]. The medical program in Adelaide had recently closed, and Melbourne Hospital had recently taken many of the prominent doctors from Adelaide Hospital [5]. This meant that not only were there positions available, but the closure of the local medical program meant that male doctors were in short supply and therefore the Hospital was willing to broaden their horizons. The positions were temporary, though Constance and Jane were both reappointed the following year [2, p.33].

In 1902, Constance obtained the position of assistant bacteriologist at Adelaide Hospital, which she held for 18 months [5]. In this position, she gave ‘special attention to the study of bacteriology and was largely in charge of the entire laboratory [1, p.219; 4, p.85; 5].

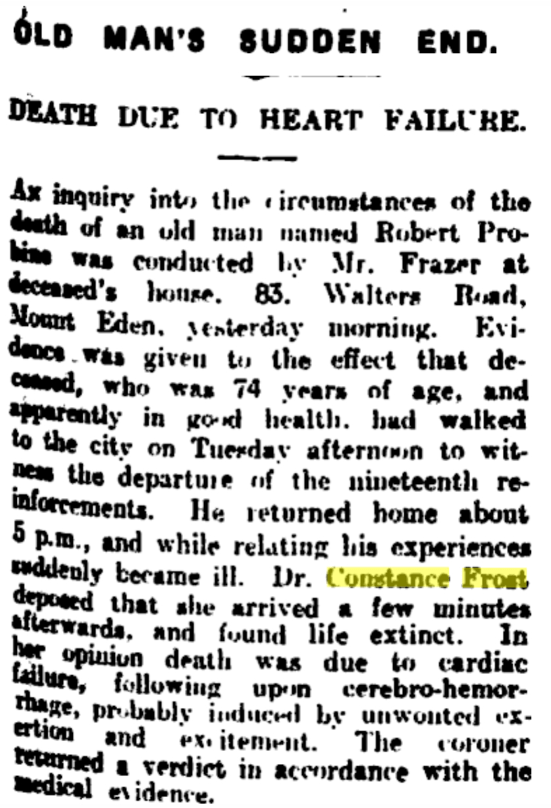

After eighteen months, Constance decided to return to New Zealand. She settled in Auckland, where she remained for the rest of her career. At first, she established a Private Practice in her home on Dominion Road in Mount Eden [5]. Constance ran hours there from 9-10am and 5-7pm. She also held daily clinics at two pharmacies: from 11am-12pm she saw patients at Fenton’s Pharmacy in Karangahape Road and from 2-4pm at Edson’s Pharmacy in Queen Street [2, p.33]. She would also take emergency calls in nearby suburbs, though her priority was to the patients she saw at the clinics. ‘This would seem a busy schedule demanding an urgency of pace travelling from surgery to surgery, which might explain why, in June 1905, the young woman doctor was charged in court with ‘driving on the wrong side of the road in Symonds Street’, and ‘driving around the corner of Khyber Pass Road and Symonds Street at other than walking pace’. Dr Frost’s explanation, that she was on the right-hand side of the road to avoid the likelihood of horse trams colliding with her carriage, was not sufficiently convincing for her to avoid being fined 5/-, with 14/- costs’ [2, p.33].

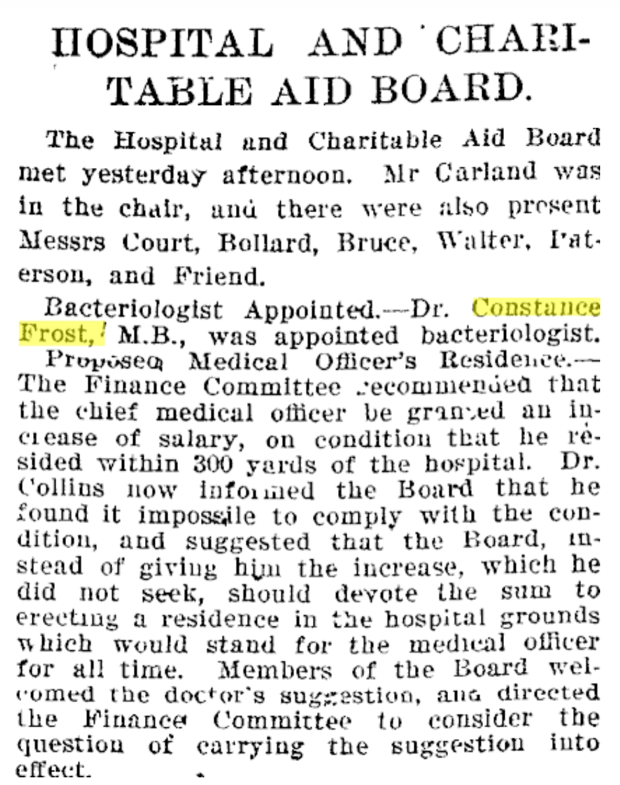

Alongside her practice, Constance also applied for and received the position of Pathologist and Bacteriologist at Auckland Hospital (the two positions were joined together at this point because there had been no other applications besides Constance’s to either appointment). In 1913, this expanded to ‘public vaccinator for the Auckland district when there was great anxiety about the severe outbreak of chicken pox which threatened the community and the Māori people in particular’ [2, p.35]. The position Constance was awarded was temporary; the Board only intended for Constance to hold the position for one year while they continued to advertise the position to male doctors. The Board had hired her because she was the only one who showed any interest in the position, which carried many risks and was therefore difficult to fill [1, p.220].

When Constance first began, ‘there was no actual laboratory set up for the specific purpose of clinical research… She acquired various basic items of laboratory equipment, though was provided with only the most necessary’ [2, p.34]. Over time, she built up her reputation as a ‘skilled bacteriologist’ [5]. From early on, Constance was ‘actively involved’ in Hospital matters [4, p.88]. She attended staff meetings and gave lectures to trainee and probationary nurses on midwifery, anatomy, and physiology. She also advocated for better working conditions in the hospital, including increasing the quality of work in the laboratory so as to improve its functionality. In 1904, she approached the Honorary Committee asking for support, as her assistant was conducting unsafe experiments in the laboratory that were of great concern to her. ‘With little laboratory experience and without authority, he would enter the laboratory and proceed to carry out unsafe experiments developing anthrax cultures, a dangerous practice of which she had voiced her strong disapproval. Despite her opposition to his presence in the laboratory the doctor, demonstrating his lack of respect for his colleague, had persisted in continuing with his experiments even though this had interfered with her own work’ [2, p.34; 4, p.88]. This scandal was reported in newspapers all around New Zealand.

The good relationship with the members of the Board and teaching benefits that Constance experienced during the first few years of her appointment made the unpaid nature of the position more bearable. However, when these benefits gradually disappeared, it merely highlighted the problematic nature of Constance’s position at the Hospital [2, p.34].

Kathleen Anderson noted that there is no known reason for why Constance remained in this continually temporary position other than that she enjoyed the work. ‘Examining bacteria and dead bodies, apart from the personal risk of infection, would hardly have attracted patients to her private practice… Perhaps she enjoyed the work and the contact with the hospital’ [4, pp.87-8] This seems the only logical reason for her continued work at Auckland Hospital, especially considering the hostile environment created by her male colleagues.

The Board of Auckland Hospital continued to pursue their search for a male doctor to fill the position of Honorary Pathologist. Over the seventeen years that Constance worked at the hospital, the position was advertised annually but they only ever received one applicant: Dr Constance Frost [4, p.86]. ‘The fact was that no male doctor would accept the poor working conditions in the makeshift laboratory’ [2, p.33]. To make matters worse, the Board kept Constance on a temporary, unpaid role for the majority of these seventeen years. In 1906, the Auckland Star reported that Constance Frost was appointed as one of three physicians at the Auckland Hospital, though it does not advise if this was a paid position or not. It seems likely that it was not, because in 1908, Constance applied to permanently move away from her highly demanding Pathology job by applying for the advertised role of Honorary Physician. Her application was denied. She once again accepted the temporary position of Honorary Pathologist – which she did so without sending the customary letter of thanks to the Board [4, p.93].

In 1908, Constance was appointed as City Council Bacteriologist, which entitled her to a small fee of one guinea per service. Her duties involved monthly testing of the city’s water supplies, and ‘testing milk and other water on various occasions as required’ [2, p.35].

In 1911, the Hospital Committee finally recognised the demands being placed on the Hospital’s Pathologist and Bacteriologist. ‘The work of the laboratory was too great to be carried out by an honorary officer alone’ [4, p.93]. The Committee recommended that the position be a salaried one (notably their conversations do not mention turning Constance’s position into a paid position). Rather, the Hospital continued to look outside, even expanding their search to the whole of New Zealand, ‘England and elsewhere at a salary of £400 per annum’ [4, p.93]. Once again, there was no interest, most likely because the salary was considered too low. In 1912, Constance was once again elected to her honorary post – without pay.

In 1913, though, the Hospital Committee finally approved a small sum to be paid to Constance for her work: £100. The reason for their change of heart on this matter was two-fold. Firstly, Constance had perpetually been writing letters to the Board advising them of the demands of her work in the hope that they would understand the pressure she was under, especially considering her work at the hospital was so time-consuming that she had little time for her private practice work that actually paid.

Secondly, a momentous change had occurred on the Auckland Hospital Board: in 1913, the Hospital hired a second woman doctor, Dr Florence Keller, and she had been elected to the Hospital Board. Until this point, Constance was the only woman doctor on staff at the Hospital. These two factors contributed greatly to the Hospital Committee’s approval for Constance to finally receive payment for her work. Where the Committee had suggested paying Constance only £100, the final Board’s approval was for £250. ‘It is unlikely that Dr Frost would have received any more than the £100 proposed by the Hospital Committee had a woman not been on the Board’ [4, pp. 98-9, 100].

Despite this small win, Constance’s position at the Hospital was continually narrowing and she was not given the opportunity to expand or develop her skills. From 1913, she was no longer giving lectures to the nurses, and she stopped attending staff meetings (whether by choice or not is unclear), even when the topics of discussion revolved around Bacteriology and Pathology [4, p.89]. In fact, throughout her entire career at Auckland Hospital, she wrote letters to the Board, though she was notably absent from the “special” meetings called to discuss their content [4, pp.85-6]. In fact, at the meetings called to discuss her letters, it appears many members of the Board scrutinized her abilities. Despite this, Constance had some support. Dr James Hardie Heil argued that Constance should retain her position rather than continue to advertise it, a motion that Dr Gore Gillon seconded [1, p.221]. However, the lack of further support meant that the motion was denied [4, pp.90-1].

Kathleen Anderson argues that the reason for this decline in Constance’s position was most likely because Dr Keller was absent from the Board for a number of years until the end of 1917. This argument is reinforced by the fact that in May 1918, Constance requested ‘to be put on whole time duties as Pathologist’ and the request was granted. ‘Once again had she applied while Dr Keller was away the outcome of her application may well have been different’ [4, pp.101-2].

With the move to full-time staff came the benefit of a pay rise to £500 per annum. Once again though, the position remained temporary and ‘as a condition of the appointment she would be expected to assist in the administration of anaesthetics when her other duties permitted… the administering of anaesthetics was certainly not a usual duty of a hospital pathologist or bacteriologist’ [4, pp.102-3].

‘Why she should be taken on temporarily when by this stage she had been working as both a pathologist and bacteriologist at the hospital for 15 years, is unclear. But what is striking, and suggests that both the hospital administrators and the Board wanted a man to head these departments, is that another doctor at the hospital, Dr Hastings, asked if his wife, Dr Violet Hastings, also an experienced bacteriologist, could be given the hospital post of Bacteriologist. The board informed both Drs. Hastings that the position has been filled. Yet three months later the position was advertised in New Zealand, England, and Australia. In view of the fact that Dr Frost only had the position until another appointment could be made, Dr Violet Hastings was effectively prohibited from applying’ [4, p.103].

Interestingly, it appears that the opinion of Constance that was so pervasive amongst the Hospital Committee and Board remained internal, at least at the beginning. In April 1906, the Committee spoke to the New Zealand Herald Constance’s appointment as Pathologist and Bacteriologist. They complimented her work, saying that it was ‘quite equal to anything of the kind in the colony. The work carried out was really of a most searching character, and most valuable’ [2, pp.34-5]. It is tragic, that this opinion did not reflect their behaviour within the workplace.

Life Outside of the Hospital

As was common for many early woman graduates, Constance felt a responsibility to share her medical knowledge with the community. As well as delivering lectures to nurses, Constance gave lectures and demonstrations to various community groups. This involved teaching first aid to St John’s groups and delivering lectures to the Women’s Branch of the New Zealand Natives Association on midwifery. She was also an active member of the British Medical Association when she had time [2, p.36].

Outside of Medicine, Constance walked in the elite sector of society. She was invited to the Vice-Regal Garden Party in May 1913, ‘at the invitation of Their Excellencies, the Earl and Lady Liverpool’ [2, p.36]. She would even travel as far as Melbourne for holidays. However, while there, she would also educate herself on the latest laboratory techniques, so it became more of a working holiday.

An Early Death

In 1918, the influenza epidemic reached New Zealand and quickly spread throughout the country. The intensity of this event led many doctors to be stretched thin, as they were not only exposing themselves to this dangerous disease, but also working extremely long hours to keep up with the demand.

In January of 1920, it finally caught up to Constance. She contracted influenza from her work in the laboratory and, on 29 January, passed away at her home on Dominion Road [1, p.221; 3, p.28; 4, p.103]. She had a small, private funeral and then was interred at Purewa cemetery. A small obituary was published in both the New Zealand Herald and the New Zealand Medical Journal. She was referred to as a doctor with ‘professional skill, kindly disposition and the capacity for self sacrifice [which] won her the esteem of an extensive circle of friends’ [2, p.36].

Notably, the Hospital finally managed to hire a male doctor to fill her position after her death: Dr Walter Gilmore. Before she had passed, Constance was on an annual income of £500 that she’d had to fight for. By the end of Dr Gilmore’s first year, he was earning £1000 per annum, making him the second highest paid doctor at the hospital [2, p.36; 5].

Bibliography

[1] Anderson, K. (1995). Constance Frost in New Zealand and Australia: a trans-Tasman look at colonial medicine. New Countries and Old Medicine, 217–222. Pyramid Press.

[2] Sherwood, V. (2015). Dr. Constance Helen Frost: general practitioner, bacteriologist, pathologist. Prospect, 14, 32–36.

[3] New Zealand Medical Journal. (1920) Dr. Constance Frost. New Zealand Medical Journal Obituaries.

[4] Anderson, K. (1992). Beyond the Pioneer Woman Doctor: A Study of Women Doctors in Auckland 1900-1960. University of Auckland Theses.

[5] Anderson, K. (1996). Frost, Constance Helen. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved on 12 Dec, 2021. https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3f14/frost-constance-helen