Class of 1904

This biography has drawn heavily on information from Papers Past and some personal information received from Dorothy Page.

Contents

Early Years and Her Family

Winifrede Ismay Bathgate was born on 25 May 1876 to early New Zealand pioneers Alexander and Fanny Gibson (nee Turton) Bathgate. She had one older sister Alison (1874) and a younger sister Dorothy (1879) and a brother John (1886). (1)

Her mother Fanny was born in England on 29 February 1845, the second born daughter of a J. Turton, Esq., from Manchester, England. (2) It is not known when she immigrated to New Zealand. She was the niece of Rev Henry Hanson Turton, a well-known early New Zealand Wesleyan missionary, who became a member of the House of Representatives for New Plymouth in 1863. (2, 3) She and Alexander were married on 24 April 1873 at St Paul’s Anglican Church, Dunedin. (4) She died at home on 24 November 1925 at 85 Glen Avenue, Mornington, Dunedin at the age of eighty-one. (5)

Her mother Fanny was born in England on 29 February 1845, the second born daughter of a J. Turton, Esq., from Manchester, England. (2) It is not known when she immigrated to New Zealand. She was the niece of Rev Henry Hanson Turton, a well-known early New Zealand Wesleyan missionary, who became a member of the House of Representatives for New Plymouth in 1863. (2, 3) She and Alexander were married on 24 April 1873 at St Paul’s Anglican Church, Dunedin. (4) She died at home on 24 November 1925 at 85 Glen Avenue, Mornington, Dunedin at the age of eighty-one. (5)

Winifrede’s father, Alexander, was born on 4 August 1845 in the market and woollen industry town of Peebles located about thirty-five kilometres south of Edinburgh, Scotland. He migrated to Dunedin in 1863 with his father John Bathgate (an Edinburgh University trained lawyer), his stepmother Mary, and 9 siblings. His own mother Anne, died in Peebles in 1851. Alexander articled with G.K. Turton (a Dunedin barrister and son of the Rev H.H. Turton) and latterly with his father, was admitted as a barrister and solicitor in 1872, and practised in Dunedin until he retired in 1909. In addition to his work as a lawyer, he was a prolific writer, including novels about colonial life, histories, and travel guides. He loved nature and was noted for his work in conservation promoting afforestation. This included the transformation of many of Dunedin’s open spaces such as the Octagon and Queen’s Gardens into neatly laid out parks. In addition, he had a significant role in bringing about the national arbor day (celebrated on 5 June). He died in 1930 at the age of eighty-five. (6)

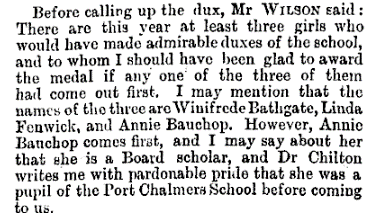

It is not known where Winifrede’s very early education occurred, but from February 1889 she attended the Otago Girls’ High School in Dunedin. (7) This school which prepared girls for tertiary education, opened in 1871 and was the first public girls’ school in the Southern Hemisphere. (8) The end of year prize giving days indicate she was a clever young woman, and her education covered a wide range of subjects. In 1891, she received the fourth form certificate for mathematics and prizes for English, Latin, and Science as well as the fifth form prize for French. In 1892, she received the fifth form certificate for Latin and prizes for English and Science. (9) In 1894, she received the sixth form certificate for mathematics and the upper sixth form prize for English, French, Latin, and Science. She was very close to being dux of her school. (10) She sat and gained credit in the New Zealand junior scholarship examinations in December 1894 with a score of 2678 (the tenth highest score in New Zealand). (11)

Otago University

In 1895, Winifrede (often called Freide) commenced her studies at the University of Otago. She wrote three scholarship exams in early April and gained the top marks in both the Scott and Women’s Scholarships but was only awarded the Women’s. (12) In 1897, she had passed the first section of her B.Sc. (13) and successfully completed it in 1900. She graduated with her MB ChB NZ in 1904 along with two other women, Agatha Helen Jane Adams and Emily Helen Violetta Nees. (14)

While at university, she was one of the three female representatives on the 1902 and the 1903 Executive of the Otago University Studies’ Association. (15)

Eleanor Southey Baker (class of 1903 who also received her early education in Dunedin) mentions in her autobiography that she and her friend and classmate “Freide” were both personally known to Dr Truby King (famous for starting the Plunkett Society and at this time in charge of the Seacliff Asylum) and his wife. In their third and fourth years of medical training the medical students would spend two weeks at Seacliffe. Eleanor and Freide spent these two weeks as personal guests in the King’s home. (16)

Career

Following graduation, she spent two years in London, England and Dublin, Ireland doing post-graduate training. (17) She spent two months doing “professional work” at Coombe Hospital in Dublin. (18) This hospital was formally opened as the Coombe Lying-in Hospital in 1829 and was granted a Royal Charter in 1867. Today it is one of the largest providers of women and infant health in the Republic of Ireland. (19) She was then appointed resident clinic clerk in the Whitworthe (chronic care) and Hardwicke (fever) Hospitals for the following three months. (18) Today, neither hospitals are operational. (20, 21)

The type of post-graduate training Winifrede focused on and where it was received during the remaining months she spent overseas is not known, but no doubt further training in ophthalmology was gained.

On her return to New Zealand she was employed by Dunedin Hospital to work as assistant surgeon to Sir Lindo Ferguson in ophthalmology and assistant surgeon to Dr A J Hall in otolaryngology. She was the first Otago Medical School graduate of either sex to be appointed to the Dunedin Hospital medical staff. (22) It is not known when she became a surgeon in her own right. She would have trained as a medical student under Sir Lindo who had trained in ophthalmology in Dublin, becoming FRCSI in 1883 prior to immigrating to New Zealand and taking up the position of ophthalmologist at Dunedin Hospital on 1 January 1884. He was appointed lecturer in diseases of the eye at the University of Otago in 1886 and also carried out ear, nose, and throat surgery. He was dean of the Otago Medical School from 1914 to 1936 and was reputed to be the first trained eye specialist in Australasia. (23)

At some point after her return from overseas, she set up her own practice in Lower Stuart Street, Dunedin. It is not known for how long Winifrede practiced medicine, but we know that her name was put forward in 1928 by the New Zealand Medical Women’s Association to the Medical Women’s International Association Council Meeting held in Bologna, Italy for recognition in her field of ear, nose, and throat diseases and that by 1933 her name had been removed from the Register of Medical Practitioners. (24) Her obituary states ill-health forced her to retire from active practice in the mid-1920s when she would have been around fifty years of age. It states her condition was painful and kept her mostly housebound. (17)

New Zealand Medical Women’s Association

Winifrede played a key role in the formation of the New Zealand Medical Women’s Association (NZMWA). At 4:30 p.m. on 27 October 1921, she hosted a meeting at her Stuart Street rooms with six other medical women with the purpose of considering the formation of a NZMWA. Others present were Dr Emily Siedeberg (class of 1896), Emily Nees (class of 1904), Ina Moody (class of 1910), Marion Whyte and Grace Stevenson (class of 1918) plus Emma Irwin (a 1907 Edinburgh medical school graduate who practiced in Middlemarch and Palmerston South). A list of 107 women known to be members of the medical profession living in New Zealand was tabled. The aims of the association were to hold meetings at which papers of interest to medical women would be read and to further the interests of medical women throughout New Zealand. The first annual general meeting (AGM) was held in February 1923. At the second AGM in February 1924, Winifrede became the national President. (24)

Other Interests

During 1910, the Eugenics Education Society was started in Dunedin with an influential membership including Dr Truby King, at the time Medical Superintendent of Otago’s Seacliff Asylum. Dr Emily Siedeberg, the first woman medical graduate from Otago Medical School, was a vice-president. (25) For the first couple of years, Winifrede is recorded as attending some of their meetings. (26, 27) The New Zealand Society came under the umbrella of the London Eugenics Society which had been started three years prior. Its early aim was to educate the public on eugenics rather than promote legislative changes. (26) She also took an extended travel trip to England in 1912 but there is nothing to indicate she went on behalf of the Society. (28)

In 1928, she took part in a Jubilee celebration of the first New Zealand branch of the YWCA started in Dunedin in 1878. Mrs. John Bathgate, her step-grandmother, was the first president of the Dunedin YWCA. (2, 30) The show was held at His Majesty’s Theatre and provided a glimpse of the achievements of the pioneer women involved over the past fifty years. Winifrede, as a descendent of the very first president, represented the first decade with her costume. (29)

During Mr Victor Bonney’s 1928 trip to New Zealand, she attended several social occasions for he and his wife Annie. These included an afternoon tea with the Otago Women’s Club, a tennis party with afternoon tea, and a Dunedin medical fraternity dinner. (30)

Death

Winifrede passed away at her Dunedin home on 15 February 1955 at the age of seventy-eight. Her obituary said she showed great courage in accepting her weak and painful condition. (17)

Bibliography

- Births, Deaths & Marriages Online Wellington: New Zealand Governent: Internal Affairs; [cited 30.05.2022]. Available from: https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz/

- McInnes E, Hackworth EW. The Bathgate Clan 1809-1970. 1970.

- The Cyclopedia Of New Zealand [Taranaki, Hawke’s Bay & Wellington Provincial Districts]: New Zealand Electronic Text Collection: Victoria University of Wellington; Former Members Of The House Of Representatives; [13.06.2022]. Available from: https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc06Cycl-t1-body1-d1-d3-d4.html#name-401540-mention

- Marriages. Otago Daily Times. 1873 28.04.1873. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT18730428.2.9

- Deaths. Otago Witness. 1925 01.12.1925. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OW19251201.2.119.3

- Vine GF. Bathgate, Alexander, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Wellington: Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; 1993 [30.05.2022]. Available from: https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2b8/bathgate-alexander

- Transcription by Eleanor Leckie of Otago Girls’ High School Admission, Progress and Withdrawal register 1887-1997 (TR-051) Dunedin [09.06.2022]. Available from: https://hakena.otago.ac.nz/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/DESCRIPTION/WEB_DESC_DET_REP/SISN 2437?sessionsearch

- Otago Girls’ High School History Dunedin. Available from: https://www.otagogirls.school.nz/about/history

- Girls’ High School. Otago Witness. 1892 22.12.1892. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OW18921222.2.131

- Schools’ Break-Up. Evening Star. 1894 12.12.1894. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD18941212.2.29

- New Zealand University The December Examinations. Otago Daily Times. 1895 19.02.1895. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT18950219.2.71

- University Council. Otago Witness. 1895 09.05.1895. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OW18950509.2.33

- University Council. Otago Witness. 1897 08.07.1897. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OW18970708.2.132

- Page D. Anatomy of a Medical School. Dunedin: Otago University Press; 2008.

- Executive of the University Studies’ Association. Otago University Review 1902 30.10.1902.

- McLaglan ESB. Stethoscope and Saddlebags. Auckland: Collins Bros. & Co. Ltd; 1965.

- Obituary: Dr. W. Bathgate. Press. 1955 15.02.1955. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19550215.2.4

- Personal Notes from Home. Evening Star. 1904 30.09.1904. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD19040930.2.6

- contributors W. “Coombe Women & Infants University Hospital” 2022 [updated 13. 05. 2022]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coombe_Women_%26_Infants_University_Hospital

- Advertisements. Hawke’s Bay Tribune. 1921 05.09.1921. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HBTRIB19210905.2.2.8

- contributors W. Whitworth Hospital: Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2022 [updated 11.04.2022]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Whitworth_Hospital&oldid=1082180425

- Wright-St Clair RE. “Historia Nunc Vivat” Medical Practitioners in New Zealand 1840 to 1930. Christchurch: Cotter Medical History Trust; 2003.

- Wright-St Clair RE. Kōrero: Ferguson, Henry Lindo Wellington Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; 1996 [03.06.2022]. Available from: https://teara.govt.nz/mi/biographies/3f3/ferguson-henry-lindo

- Maxwell MD. Women Doctors in New Zealand. Auckland IMS (NZ) Ltd; 1990.

- Eugenics Education Society. Otago Witness. 1910 07. 09. 1910. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OW19100907.2.58

- The Eugenics Education Society. Otago Daily Times. 1910 23.08.1910. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19100823.2.44

- Eugenics Education Society. Otago Daily Times. 1911 05.05.1911. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19110505.2.83

- In the Homeland: New Zealanders on Tour. New Zealand Times. 1912 11.12.1912. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZTIM19121211.2.6

- Notes for Women. Otago Daily Times. 1928 10.07.1928. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19280710.2.121

- Personal and Social. Otago Daily Times. 1928 09.03.1928. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19280309.2.151.1