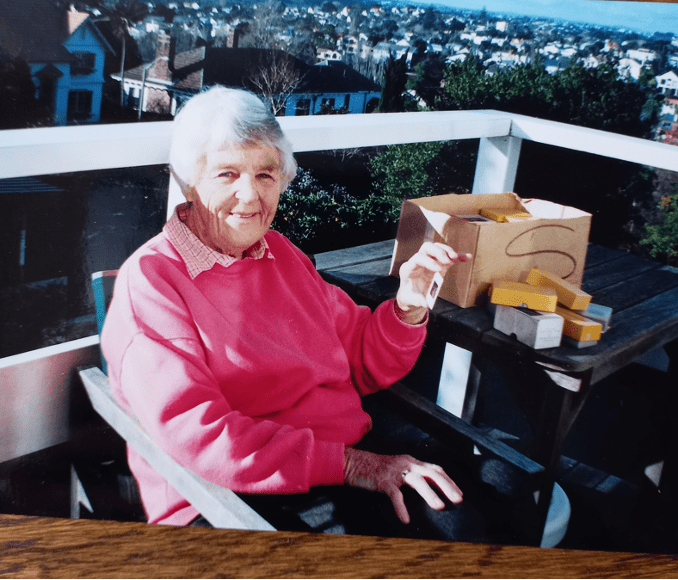

This biography is based on information from the biography “Teaching Hundreds to Heal Millions – the story of Dr Beryl Howie” written by Bartha Hill and interspersed throughout this biography are quotes from this book. (1) Beryl’s nephew and niece have provided further information on their Ngāi Tahu lineage and access to family photos. The feature photo was taken Easter, 1995. Other secondary sources are listed in the bibliography. This biography was collated by Rennae Taylor.

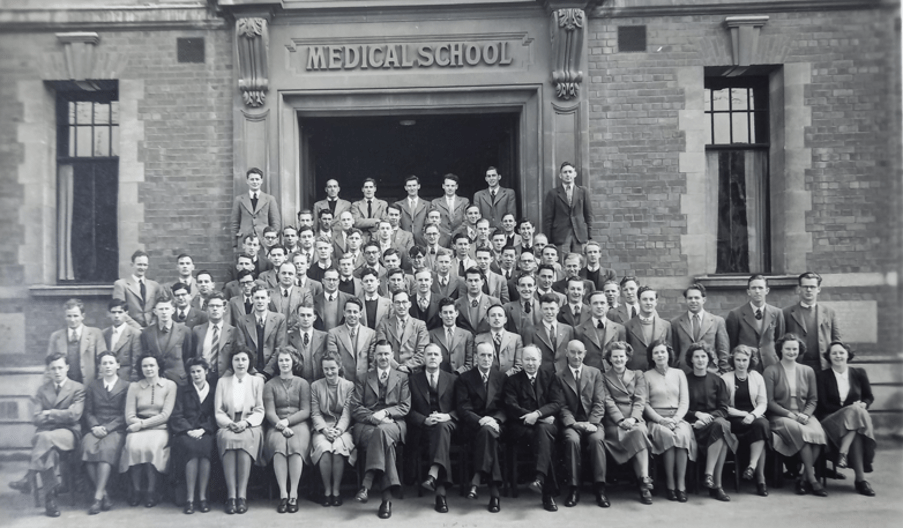

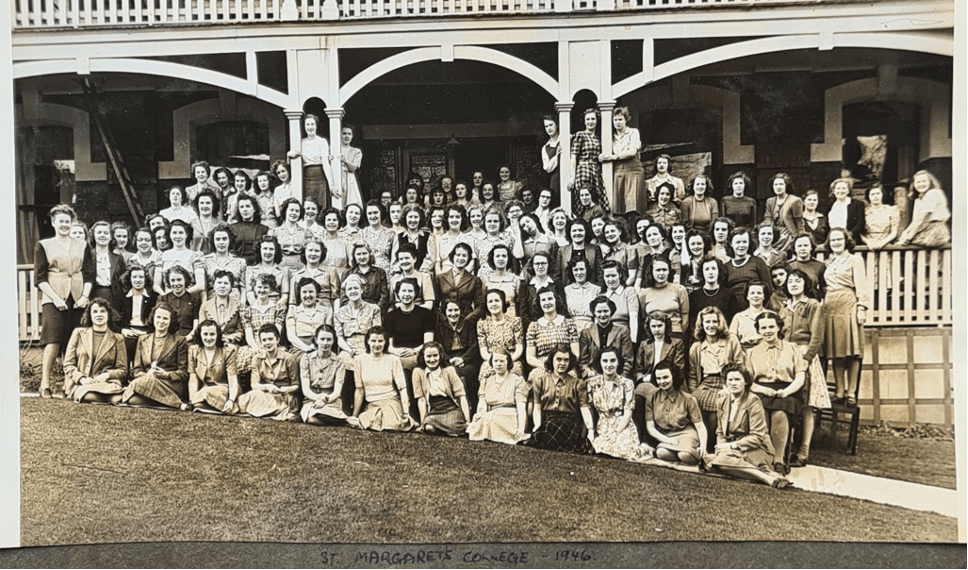

Class of 1949

Contents

Family History and Early Childhood

Beryl was born into a family which had known links with Māori, English and Scottish roots. The lineage of her mother, Gertrude Mary Howie nee Stevenson, born in 1896, can be traced back to the early nineteenth century when those involved in the South Island sealing and whaling trade would enter into interracial marriages with women from the Ngāi Tahu tribe. Beryl’s maternal lineage can be traced back to her great-great-great grandmother Te Wharerimu (Martha Brown) born circa 1809 (2) who married the sealer Captain Robert Thomas Brown who was born in Sydney 18 June 1794. (3) They lived in the early settlement of Whenua Hou/Codfish Island off Rakiura/Stewart Island. (3)

Papers Past indicates Beryl’s mother Gertrude went to the Southland School and received a prize in general proficiency and was successful in achieving a Junior Board Scholarship in December 1909 with a score of 517 at the end of Standard VI. (4) Gertrude worked as an office stenographer for Wright Stephenson & Co Ltd, a stock and station agency, in Invercargill where she met Beryl’s father, John Ruskin Howie, a first generation New Zealander, of Scottish descent. From John’s father’s obituary, it appears he had retired as a bank manager in Kilmarnock, Scotland due to poor health at around the age of forty-four and then emigrated to Invercargill, NZ. Shortly thereafter, he met and married Margaret Wright Todd in 1889. They reared a family of five sons and four daughters. Two of the younger boys went on to become doctors and served as overseas missionaries in China and India. John was the sixth born in his family and left school at the age of sixteen to help support the family as his father was retired and elderly. He worked as an office boy at the same company as his future wife and received regular promotions. He and Gertrude were married at St Paul’s Presbyterian Church in Invercargill in 1922, moved into a newly built home and welcomed their first born, Beryl Overton Howie, on 7 November 1924. As an infant she was nicknamed “Bardy” – a pet name which was used within her family until her death.

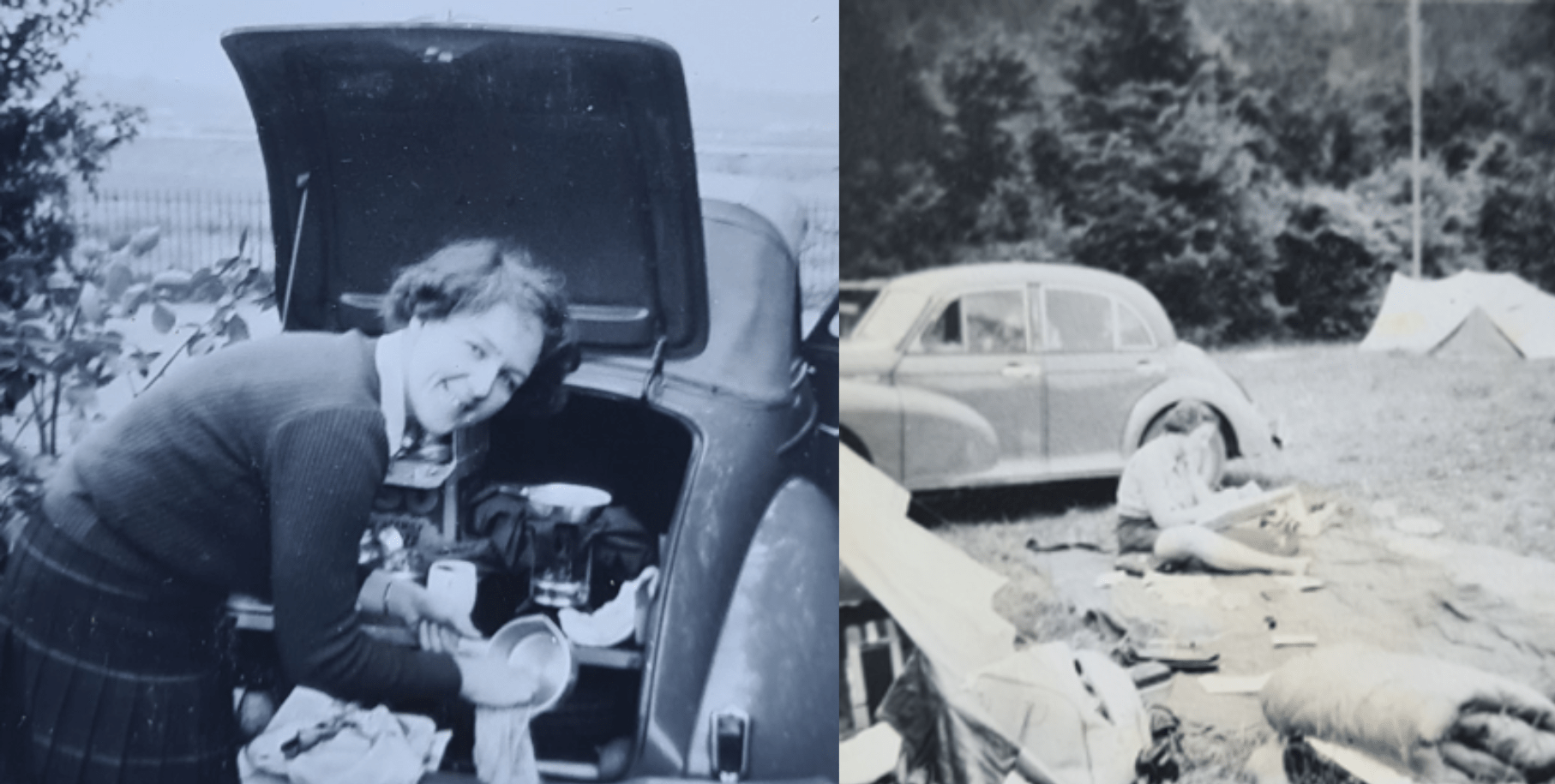

Soon after the birth of Beryl, her father accepted the post of travelling representative in Wright Stephenson’s Auckland branch. They lived in Mount Eden where they welcomed their second child, John Stevenson Howie, on 27 May 1926. The family lived in this suburb for the next twenty years and over the years many of their extended family moved from Southland to Auckland. Beryl remembered their home as a happy caring environment. Music was important in their home and they had a gramophone and piano. The children helped in their vegetable garden on a Saturday and they attended their local Mount Eden Presbyterian Sunday School on a Sunday. Their father had a company car, and later a family car, which the family used for picnics at local beaches. They would often camp at northern beaches in their tent and later in a caravan. Every other year, after their camping holiday, Beryl and her brother went with their mother to visit family and friends in Southland.

Auckland School Years

Beryl started at Mangawhau Primary School at the age of six. Unfortunately she caught diphtheria during her first year at school and had to have an emergency tracheostomy and spent several weeks on the Infectious Diseases Ward at Auckland Hospital. It was a frightening time for a six year old as her parents were not allowed to visit her. She did enjoy the daily visits from her Uncle Tenny, her father’s younger brother, who was a junior doctor on the ward. She celebrated her seventh birthday during this time and when she was well enough to be discharged home spent another month convalescing before recommencing her schooling, this time at Epsom Normal Primary School where some of her cousins attended. During the long days of resting, Beryl enjoyed reading her books, especially an illustrated Bible story book.

As a young girl Beryl was introduced to overseas mission work and some of the challenges missionaries faced. Her father’s two younger brothers, her Uncle Hallam and Uncle Tenny, both went to China as missionary medical doctors. Sadly her Uncle Tenny died of acute endocarditis in 1936 at the age of thirty-three, during the family’s first furlough home. His eldest son Ross later became the Head of Neonatal Medicine at National Women’s Hospital, Auckland and was well known for the clinical trial he and Professor Mont Liggins ran in 1972 which showed two corticosteroid injections given to women at risk of preterm birth significantly reduced the incidence of respiratory distress in their infants. This practice is now used globally. In 1942, her Uncle Hallam and Aunt Mary and their children were interned in China by the Japanese invaders for three years.

Beryl enjoyed her secondary school years at Epsom Girls Grammar School and participated in many activities including music, art, drama, swimming, tennis, cricket, netball and hockey. She joined the school choir, continued her piano lessons, learned to play the cello and was in the school orchestra. In her sixth form, she became a prefect.

During her secondary school years she continued attending Mount Eden Presbyterian Church Sunday school and was greatly influenced by the girls’ Bible Class leader, Millie Sims (nee Reid), who encouraged her students to read the bible during the week and each Sunday would ask them: “What have you found in the Scriptures that has meant a lot to you this week?” At the age of fifteen years, on 5 May 1940, Beryl made a commitment to become a follower of Jesus Christ. Beryl read many missionary biographies during these years and became involved in Scripture Union and her school’s Crusader group.

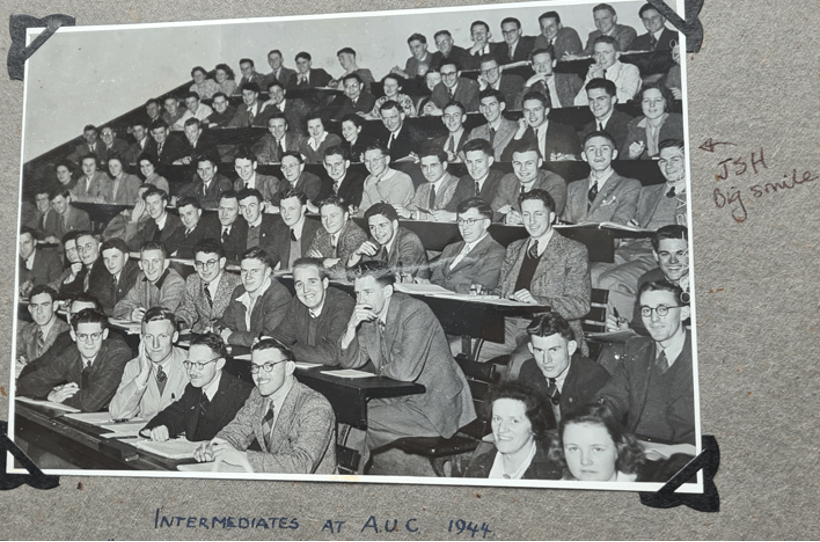

Beryl had wanted to be a doctor for several years but her parents felt teaching would be more appropriate for their daughter. Money for study was not easy to find in the post-depression years and she did not want to put this financial burden on her parents. She prayed that God would enable her to win a University Entrance Scholarship which would assist with fees if medicine was to be her future. In early 1942, her father was in the Home Guard and they were told the Japanese were on their way to NZ. He sent his wife and children to Invercargill where Beryl and her brother John attended Southland Girls’ and Boys’ High Schools respectively for three months. This school did not teach Botany to University Entrance level so Beryl had to study it independently. Despite this challenge, at the end of the year Beryl’s name was on the list of the twenty successful University Entrance Scholarships with a score of 1423. (5) She believed this was God’s confirmation that she was to study medicine and enrolled at Auckland University College to do her first-year pre-medical studies. She enjoyed university life and played in the university hockey team and became involved in the Evangelical Union. She realized at the end of the year, when she failed physics, that she had enjoyed the social life too much and hadn’t worked hard enough.

She lost one year of her scholarship but worked hard the following year on her physics and also took organic chemistry stage two and obtained marks high enough to be accepted by Otago Medical School.

Otago Medical School and House Surgeon Years

The Howie family made a significant move south in 1945. Beryl began studying medicine and her brother John dentistry at Otago University and their father was appointed manager of Wright Stephenson’s Timaru branch.

During the next three years Beryl lived at St Margaret’s Residential College for women and in 1947 was the College’s Students Association President. During this year she moved into the self-catering flats in ‘Huntley”, adjacent to and belonging to the college – there the young women cooked their own meals, did their own cleaning, maintained the gardens around the cottage and St Margaret’s retained the right to screen visitors. (6) Beryl’s scholarship and a small savings account from her grandparents allowed her to pay her fees, room and board and incidentals.

Beryl had learned her lesson in her first year of university, and applied herself to her studies and had no further failures.

She continued to enjoy hockey, led the Otago Girls’ High School Crusader group and was a keen member of the Otago University Evangelical Union.

During the summer breaks she joined the Pounawea Girls’ Crusader Camp leadership team located in the Catlins. She and her brother John enjoyed holidays with their parents in the family caravan, often staying at the Wanaka Showgrounds and having day excursions.

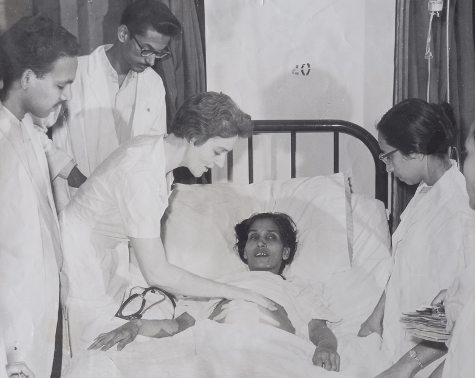

During her sixth year, Beryl went to Christchurch Hospital and boarded privately with a woman in Papanui. She passed her final MB ChB exams in December 1949, and started work as one of four house surgeons, two junior and two senior, at Timaru Public Hospital. There were no registrars here so the house surgeons worked directly with the senior consultants. Beryl obtained broad experience in general and emergency medicine, general surgery, orthopaedics, paediatrics and gynaecology, and was trained to give straightforward anaesthetics. Her obstetric experience was confined to assisting with Caesarean sections as local GPs took personal private care of normal deliveries.

During her second year, Timaru born Professor Robert Macintosh, a Nuffield Professor and head of the Department of Anaesthesia at University of Oxford, was visiting his family and called into the hospital and spoke to the house surgeons. Beryl said she was considering doing a postgraduate Diploma in Obstetrics the following year which would mean going overseas. He asked if she’d consider coming to Oxford. Beryl’s aunt was married to John Stallworthy, a senior consultant in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Dept of O&G) at Oxford, so had not considered it appropriate to apply there. Before he left Timaru, Professor Macintosh encouraged her once again to apply to Oxford. She applied directly to the administrator of Radcliffe Infirmary, not to the Dept of O&G, for a position in O&G. By the end of the year she had still not had a response to her application but was not too concerned and decided she’d go over to the UK regardless and apply for a training post when she arrived.

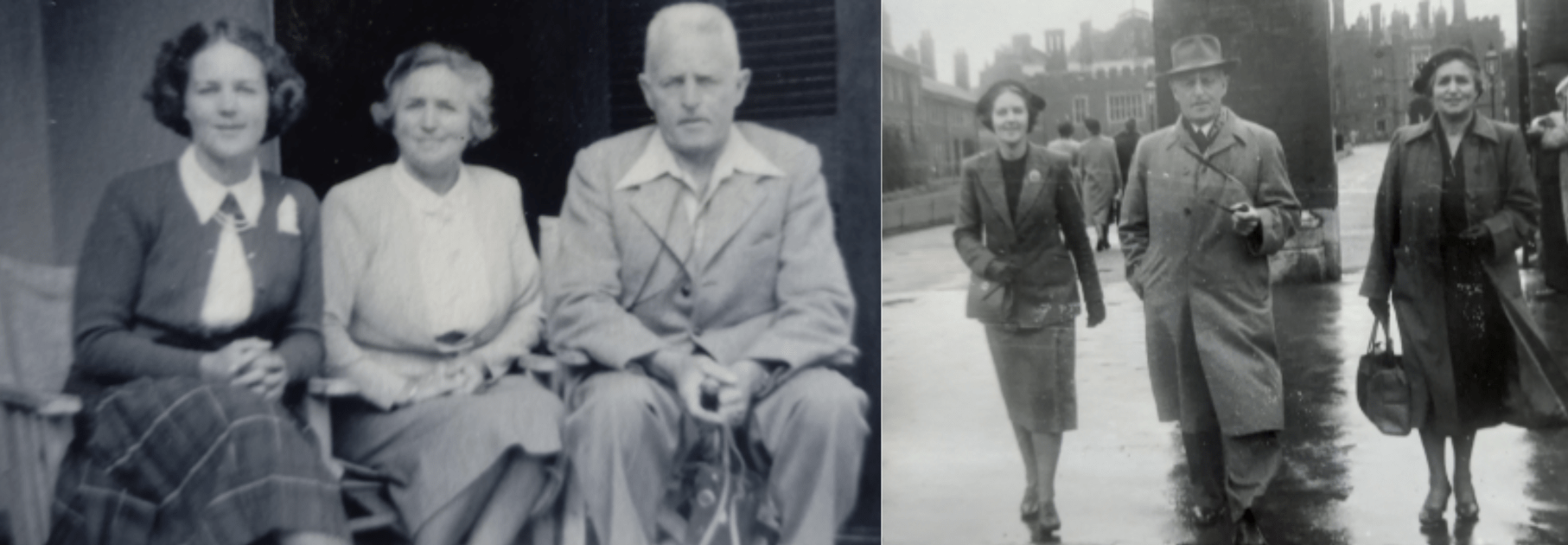

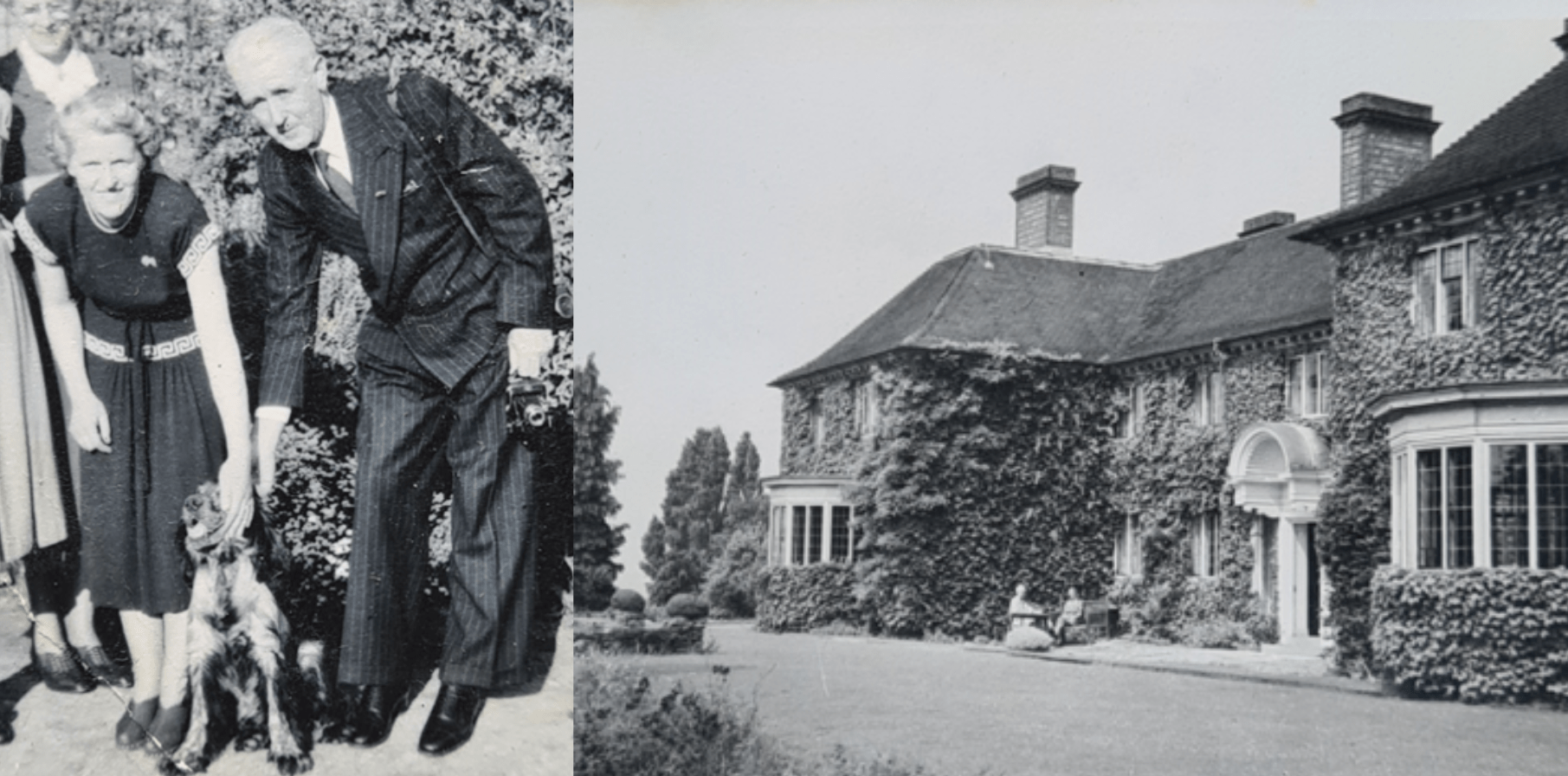

Her father’s company had increased their export of small seeds to the UK and the company wanted him to go to the UK in early 1952 to meet with the importers. His wife accompanied him and this timing also worked for Beryl to travel with them on the Orcades RMS which went via Colombo and the Suez Canal route. As their ship pulled into Gibraltar (where they planned to visit the gravesite of her father’s eldest brother who had suffered injuries during Gallipoli and subsequently died on the hospital ship and was buried at Gibraltar) another ship was pulling out as they arrived and someone was shouting “Beryl! You’ve got a job in the department – I’ll see you in Oxford.” It was her uncle John Stallworthy, married to her father’s sister Margaret (Peggy), returning from a European medical conference. She later found out he had no role in her appointment which pleased her. Someone else was responsible for the house surgeon appointments and she had been accepted on the advice of Professor Macintosh. In London they were met by her brother John who was doing a post-graduate residency in oral surgery, who took them to the Stallworthy’s home in Oxford. Their home, called Shotover, became her home away from home for the next six years. They set aside a room for her to use when she was free and every other weekend she would usually spend time there.

United Kingdom Years

Beryl studied and worked in the United Kingdom from April 1952 until the end of 1957. Over these years Beryl acquired a little Morris Minor convertible, called ‘Anna’ (short for Anaphylaxis), which she later replaced with another little car which she called ‘Proph’ (short for Prophylaxis) and enjoyed exploring the surrounding countryside as well as a trip into Switzerland with another Otago colleague Pat Mackay (nee Wilson).

On her Sundays off, she attended the vibrant St Aldates Church with the Stallworthy’s, a church frequented by Oxford students. She was exposed to the large collection of recorded music at the Stallworthy home and started to build up her own collection of music and eventually acquired a stereo Hi-Fi.

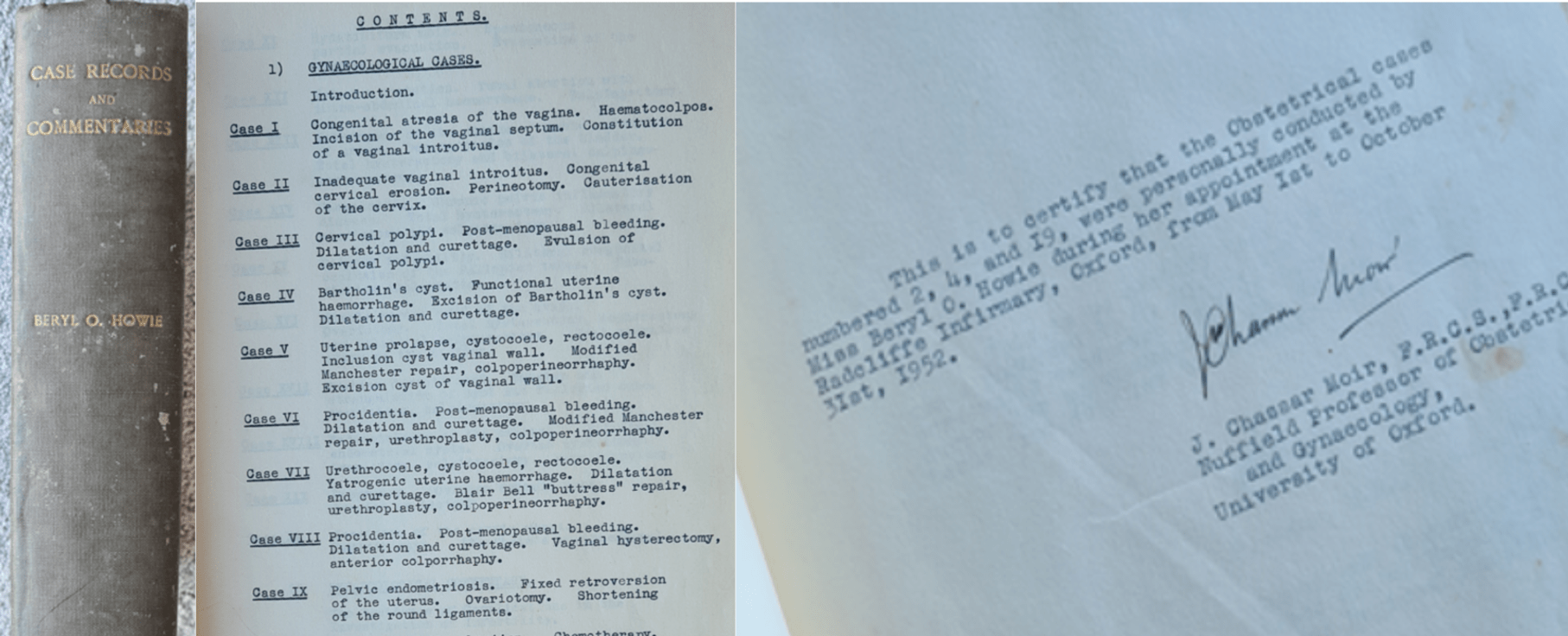

During this era there were two O&G departments in Oxford – at the Radcliffe Infirmary there was the professorial unit and then there were area departments which were headed by her uncle. The area departments were also at the Churchill Hospital in Headington, Oxford and there was a small private hospital across from the Radcliffe. Beryl spent time in the Radcliffe department during her first six months and at the end of this period she gained her Diploma of O&G, the first step towards becoming an O&G consultant. Her next goal was to sit the exam for membership of the Royal College of O&G (MRCOG). This required a minimum of twelve months obstetrical and twelve months gynaecological resident work as well as case notes and a written commentary on an obstetrical and gynaecological topic of her choice.

Beryl spent the following six months as a house surgeon in gynacology in the area department, followed by six months in obstetrics at St Margaret’s Hospital, Leeds. She then did six months in gynaecology at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Aylesbury, Bucks. In January 1955, she sat and passed the exam for MRCOG and then was invited to be a registrar at Oxford to do post-graduate training. Beryl was also involved with undergraduate medical training.

Beryl found the Oxford environment with its high-powered weekly clinical meetings stimulating. She also took her turn going out with the ‘Flying Squad’ – an emergency midwife service which had been established by her Uncle, John Stallworthy, during World War II and which continued after the war. In response to a phone call from a regional midwife or GP, equipped with instruments and blood transfusion supplies an experienced duty registrar along with a nursing sister and a house officer would set out to take care of the obstetric emergency in the wider Oxford area.

Towards the end of 1955 Beryl flew home for her brother John’s wedding in Dunedin. The trip took a few days with touchdowns in Newfoundland, Toronto, Calgary, overnight in Vancouver, down the Pacific via Honolulu and Fiji, then Auckland and finally Christchurch. During her time back in NZ, she was able to help her parents pack for their move back to Auckland as her father had been appointed Auckland branch manager with his company. She enjoyed being the medical officer with a Girls Crusader Camp at Whangarei Heads and meeting up with some of her old friends. She travelled back to the UK as ship’s surgeon on a cargo ship with sixty crew and twelve passengers. The most serious problem she encountered during the one month voyage across the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans was a passenger’s broken wrist. In addition to free passage, she was given one shilling in payment.

On her return to the UK she resumed her work in the O&G Department at Radcliffe Infirmary. Beryl was now thirty-one years old and eager to find God’s direction for the next phase of her life. In 1944, while at Auckland University, Beryl had signed on as a member of Inter-Varsity Missionary Fellowship and had committed herself to serving God overseas as a missionary. She was well aware that such a calling would probably limit her chances of marriage which in later years often came up while serving in India. Her singleness was contrary to the Indian family culture and they mostly thought her parents had failed in their duty to arrange a marriage for her. Early on Beryl had felt called to China but it was now closed to expatriates following the Communist takeover in 1949. She investigated a few leads but they did not seem a good fit for her skills.

One of Beryl’s Oxford ex-students had gone to work at the Christian Medical College and Hospital (CMC) at Ludhiana in the Punjab in India – very near the Pakistan border. When a position in the O&G Department came up, her name was mentioned and before long she was sent a letter from the London office of the Ludhiana Fellowship inviting her to apply for the senior staff member and head of the O&G Department position at the CMC hospital. Beryl knew a little about CMC but had never considered it as a possibility. After prayer, she felt she should apply and see if this might be where God was leading her.

Her father had taken early retirement due to his failing health so he and his wife were on their way to England to spend a year there. Before sending in her application in April 1958, Beryl talked it over with her parents on their arrival and received their blessing. She was accepted but had advised CMC she would not be able to take up the appointment until January 1959 when her parents would be leaving England. However, in late November she received an urgent message asking her to leave for Ludhiana immediately as they were desperately short staffed. With her parents blessing she packed her bags and left in December and docked in Bombay on 5 January 1959.

Christian Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, India

First Term

Beryl was met by an agent from the Inter Mission Business Office who helped her to clear customs and took her through the congested streets to the Bombay CMS guest house for the night. She was taken to the train to Ludhiana the following afternoon and was sent on her way for the thirty-six hour journey in her own compartment with its own loo. During these first two days, she had to learn quickly how to use a mosquito net, take a bath by throwing water over herself with a dipper and a pail of hot water (to which she added cold water from the tap), go to the loo via a hole in the floor of the train. She was met by a welcoming committee at the station in Ludhiana and taken to her CMC home for the next two decades of her life.

Beryl had her own bed-sitting room with a walk-in closet and a separate bathroom with a hand basin, cold tap and a flush toilet. It was located behind the college chapel and her door opened on to a small grassed yard which she shared with Dr Eileen Snow, the principal of CMC. Each morning, a housekeeper brought her a breakfast tray and cleaned her room. Her other meals were taken in the staff dining room (Indian food at lunch and an English menu at dinner). She often missed the appointed meal times so would prepare her own meals. A missionary family returning home left her a fridge which made life easier. A maid would bring chapattis, vegetables and dahl for her to reheat. Meat was scarce. Her laundry was taken by a dhobi (a washer person) to a local stream and bashed with a stone before drying and ironing. In later years, someone in Auckland sent her a washing machine so her clothes lasted much longer. During the winter she wore a white coat, in the summer she wore a Salwar Kamese (loose trousers with a knee length top), and on social occasions she wore a sari.

When her luggage was delivered, the amplifier and turntable she had brought with her were severely broken and Beryl burst into tears. It was the one item she had hoped would survive as she loved her music. The three-speaker system was undamaged and a few days later a friend was able to fix up the main part. It served Beryl well throughout her years at Ludhiana.

Background on Ludhiana Hospital

Dame Edith Mary Brown, (24 March 1864 – 6 December 1956) was an English doctor and medical educator. She founded the Christian Medical College Ludhiana in 1894, the first medical training facility for women in Asia, and served as principal of the college for half a century. (7) The hospital was built in stages as finances were raised, with the O&G building completed in 1927. After World War II and the partition of India and Pakistan, the hospital become co-educational. A new hospital was built after the war as a result, but the O&G building remained and was somewhat dated on Beryl’s arrival.

The London office of Ludhiana Fellowship had appointed Beryl as Head of the Department of O&G but had neglected to tell the people most affected. For a time tension was high as a newly qualified O&G specialist had been doing the job very well prior to Beryl’s arrival. This oversight was eventually sorted but the initial atmosphere was uncomfortable for a time.

Beryl’s parents both became unwell after her departure from the UK and she felt she should go back and travel with them back to NZ. After only three months at Ludhiana, a short term replacement became available and she flew to the UK. As they were going through the Panama Canal her father had to be taken to the Christabel American Military Hospital where bowel cancer was diagnosed. He had an emergency colostomy before flying home to NZ where he had the cancer removed and the colostomy closed. This time away from Ludhiana gave Beryl the opportunity to assimilate the experiences of her orientation and to prepare for the challenges ahead.

In the early years, Beryl had to fit in language study between three and four o’clock. She also had to choose which language to learn:

“Her language tutor gave her three options: Urdu which he said was the language of intellectuals and academics at university and was traditional in much of West/North India, Hindi which had now become the national language of India, or Punjabi which all the local people spoke. Her teacher narrowed it down: “If you want to relate to people all over India, you should choose Hindi,” he said. “But if you want to communicate with the local people, choose Punjabi the language everyone, especially women speaks at home.” So Punjabi it was. After awhile she could communicate quite well but often found it difficult to understand her patients. The young doctors and students would not correct her as this was seen as insulting.”

Beryl was told on her arrival the drinking water from the tap (from their own well) did not need to be boiled. Eighteen months later she came down with infectious hepatitis. While recuperating, she developed amoebic hepatitis and was put in her own private room in the hospital where she ended up teaching her students from her hospital bed. She had several discouraging weeks before resuming her duties. It was fortunate this did not happen in the first thirteen months as she was the sole senior O&G specialist and had only one weekend off during this time.

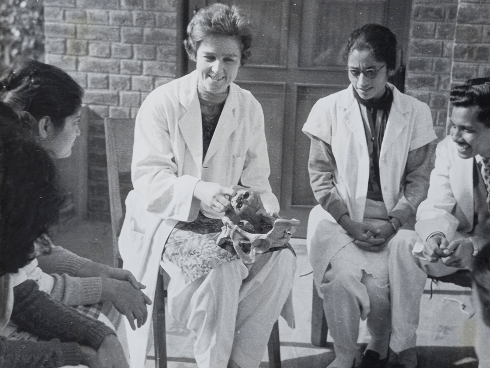

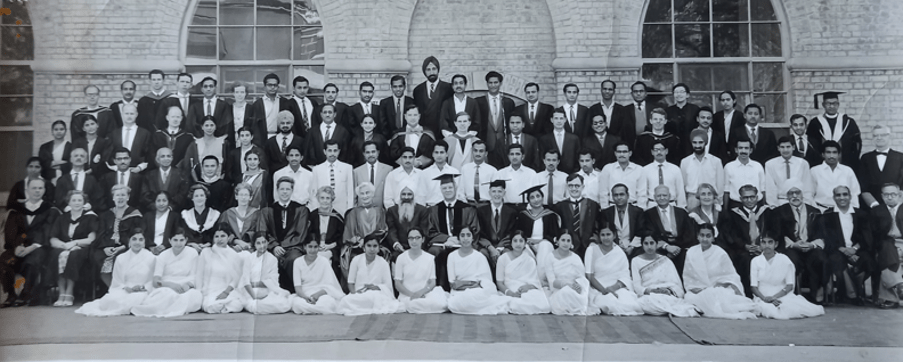

It took three years for Beryl to receive academic recognition from the University of Punjab. She was promoted to full professor on the basis of her postgraduate degree and teaching experience at Oxford. In this capacity she was sometimes expected to act as an external examiner which she found interesting. The Ludhiana student intake was limited to fifty but some other institutions had intakes in the hundreds.

After four years Beryl applied for formal recognition from the University of Punjab for her graduate UK Doctor of Medicine, MD programme. At the time, if students wished to do postgraduate training they had to go to Bombay, the UK or the USA. Being exposed to the high tech overseas hospitals they stayed in these countries after their training finished. In addition, their families put pressure on them to go abroad and get well paid jobs so they could send money home. Recognition of the CMC MD programme was a strategically important achievement for Beryl and CMC as it aided in keeping her students in India where they contributed to their own countries health care needs.

“The young doctors who graduated with their MB.BS, could do an eighteen month Diploma of Obstetrics. The MD programme took a further two years. Each student undertook research in order to present a thesis describing original research on a practical topic. Beryl helped each of her students to choose topics that were clinically relevant and necessary for India. The students were expert in rote learning – some knew their textbooks off by heart. This wasn’t Beryl’s way of learning and she would ask them questions which could not rely on rote learning. She met with her thesis students twice a week and no one could get an MD by just reading a book.”

Towards the end of her first term (five years) the governing body of Ludhiana CMC and Hospital decided to use what funds they had to pay Indian doctors, and so expatriate employees needed to find alternative sources of funding. Quite out of the blue she received a letter from the Overseas Missionary Committee of the NZ Presbyterian Church who wished to put more of its resources into the Punjab area and wondered if she would agree to be appointed a Presbyterian missionary. It was an answer to prayer for Beryl.

She left CMC on 19 December 1963 andwas on the Church’s payroll from the start of her first furlough. She was able to leave Ludhiana well resourced with medical personnel including Dr Bruce Conyngham, a NZ obstetrician, who stayed for eighteen months and was especially helpful in advancing family planning work at CMC.

Beryl wanted to qualify as a General Surgeon, as leading obstetricians and gynaecologists at the time also had this qualification and it was generally expected in a university professor. CMC had asked her to consider doing work towards obtaining her Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (FRACS) during her furlough. It consisted of two parts. The first part was basic sciences (human anatomy, physiology and pathology) which she completed on her first furlough. She did a basic course in anatomy at the University of Auckland and then moved to Dunedin from August to November for three months of intensive study, and at the end of the year passed.

Second Term

Later in 1965 war broke out in the Kashmir, an area further north from Ludhiana, and this affected CMC. The hospital received casualties, blackouts were enforced, and staff and students often had to retreat to the trenches during air raids. A peace accord was signed at the end of the year and approximately 250,000 refugees were housed in tents about 200 miles from Ludhiana. The hospital sent regular teams of doctors to help in their medical care.

Early in 1966, Beryl received news that her father was very ill and was not expected to live. She made arrangements for her cover and quickly returned to NZ to assist in his care. He died on 15 April and shortly after she returned to Ludhiana.

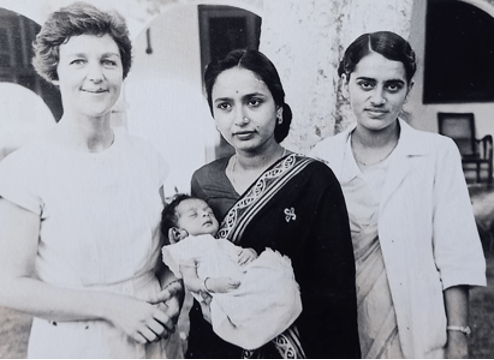

Beryl had been able to develop the capability of her department and in this second term her top priority was the postgraduate training of specialists in O&G. One of the jobs she particularly enjoyed was the one-on-one meetings with students in the MD programme to monitor and to help them find a research project which they would find meaningful. She tended to direct them towards clinical problems which might potentially improve the care of patients. Some of these research projects did lead to improvements in hospital practice. Two significant projects included discovering the best way to immunize babies against tetanus (a fairly common and often lethal illness affecting babies) and the best way to immunize babies against tuberculosis (an illness of epidemiological proportions in India). There was regular growth in the O&G staffing capability. The training system was working well with house surgeons moving on to become registrars. They were doing diplomas with two or three sitting the exams each January and October. Every year, two or more of her staff achieved their MD and went out to work across India, but a few also remained at Ludhiana. Beryl was an excellent communicator and would keep in contact with these graduates.

At the end of 1969 Beryl took her second furlough. In addition to reporting her work to churches and other supporters, she prepared for Part II of the FRACS. She spent two and a half months in the Auckland Hospital Library catching up on general branches of surgery, then went to Dunedin to do the written and practical clinical exam. She was successful and returned to Ludhiana in February 1971 as a Fellow.

Third Term

In March 1971, Ludhiana was again subject to blackouts, due to the war which broke out between East and West Pakistan (separated by 1600 kilometers of India) after it gained its independence. Although both were largely Muslim, East Pakistan was 15% Hindu and the rules of Muslim were less stringently followed while West Pakistan controlled the government, economy and armed forces. A nine month war between the two sides occurred with the final outcome being East Pakistan became independent and was thereafter called Bangladesh. CMC once again had a medical team serving the wounded. During this time Beryl became unwell and tests showed she was very anemic. She underwent a hysterectomy at her own hospital as she felt they were very capable of giving her good medical care.

During this term, one of Beryl’s MD students carried out their research project on the care of women and babies in one of the slums serviced by CMC. He found the care was very inadequate and was carried out by local midwives (dais) who had little or no formal training. Problems were not identified during the pregnancy, and during labour and delivery the women often suffered severe injuries. Preterm babies had a high rate of mortality. Beryl and her student refined his recommendations for a new concept of maternal and child health care – they proposed a new type of worker with an enlarged scope of providing home-based mother, child and family care. They trained mature women from within their own communities who had life experiences in birthing and caring for children, and added basic instruction in how a hospital worked and what it could provide including family planning, antenatal care, newborn growth and development and the importance of immunization. They were called ‘Lay Urban Health Workers’ (LUHW). Beryl proposed to Oxfam that a two year trial to train and test the efficacy of these workers should be trialed and they agreed to fund the project. CMC advertised and selected six women from within the trial semi-slum community. They ranged in age from 22 to 50 years and all had married between the ages of 16 and 20 years. Two could not write but all could read. The programme was compared to another region where CMC had trained field health workers for a postpartum programme. The community midwives continued to do the homebirths but the LUHW would refer the high risk pregnancies to the hospital during their antenatal care. The study was an overwhelming success and in December 1979 Beryl presented the results at a WHO workshop in New Delhi showing that LUHWs were an achievable solution for improving the health of mothers and babies in India, especially in the area of immunization and family planning which the country was focusing on more. In addition, it was economically feasible.

During 1972, Beryl was faced with many of her senior staff moving to other positions or else retiring. Beryl felt there was an urgency to replace them with nationals and over the next several years more indigenous and Ludhiana-trained doctors qualified and joined the staff. In addition, Beryl expanded the training program to meet the needs of CMC hospital and beyond so it became less reliant on foreign staff as it was gradually becoming more difficult to gain work visas in India. In 1973, the London-based Royal College of Obstetrics & Gynaecology gave official recognition to CMC O&G Department for training for their membership exam (MRCOG). Previously, they were required to gain this qualification in the UK or the USA.

During this term Beryl enclosed a portion of her verandah, which gave her a separate bedroom where she was able to host guests. She also had a short time of leave in February 1975 where she attended the Otago Medical School centennial and spent precious time with her mother who died of a coronary not long after her return to Ludhiana.

Major Building Project

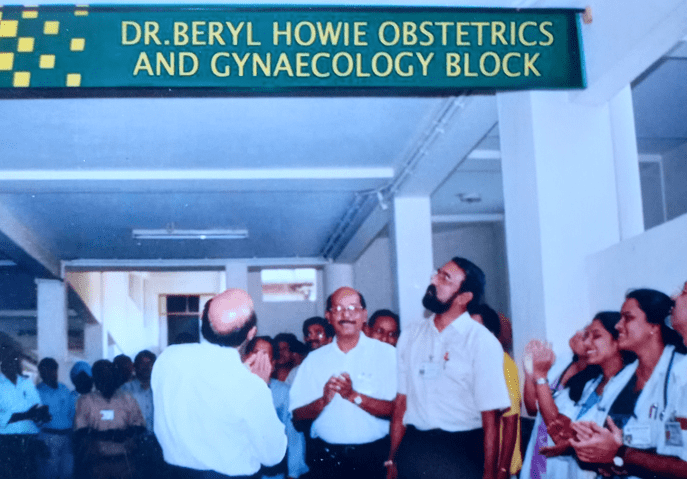

During Beryl’s time at CMC, the population of Ludhiana had doubled and the O&G building had become more and more inadequate for the needs of the women. Space had been left for a new O&G block when the CMC hospital had been built several years previously, but the years went by without any progress. Beryl was encouraged to plan for a new facility by Sir Douglas Robb from NZ who had the experience of establishing the Cardio-Thoracic Surgical Unit at Auckland’s Greenlane Hospital. So she and her team planned and designed an O&G building with six floors plus the basement. The quote to build was approximately $1.6 million NZ dollars. In May, 1975, the NZ government provided a conditional grant of NZ $500,000 subject to the remaining dollars being raised by 31 December 1977. Miraculously, the remaining money was sacrificially raised almost to the day by the people of NZ and the building program was able to proceed. In May 1978, the NZ High Commissioner was able to participate in the ground-breaking ceremony.

After the ground-breaking ceremony, concerns arose about the O&G building and the cost of running the facility. In the past CMC resources designated for a specific building had been redirected where the needs were greatest. The then director of CMC felt the O&G block was no different. This was a difficult time for Beryl as she found her design was much changed to accommodate other’s needs. One floor became a quality Cardiology Dept with a Coronary Care Unit and Cardiac Catheter Suite, while part of the ground floor became the Electronics workshop. However, the finished O&G facility was able to provide quality care into the following decades. It was opened on 9 October 1982 and on 12 December 1982 the new six floor wing bearing Beryl’s name was dedicated by the moderator of the NZ Presbyterian Church.

In later years, when Beryl was receiving medical treatment at her local Auckland hospital, an Indian trained doctor admitted her. She asked him if he had ever heard of Dr Beryl Howie to which he replied: “I wasn’t trained at her hospital, but I know all about her – and so does everyone in our province.” Her vision of ‘Training Hundreds to Heal Millions’ was happening, but not perhaps in the ways she envisaged.

In the 1979 Queen’s Birthday Honours, Beryl received a Companion of the Queen’s Service Order for public services and the NZ High Commissioner presented her with the honour in New Delhi. The inscription read:

“To our beloved and trusted Beryl Overton Howie. That is what Dr Howie had been to countless Indian mothers in the Punjab as she has served the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecoloy at the Christian Medical College in Ludhiana as a very competent and trusted doctor.”

Beryl returned to NZ in July 1980 to have a growth removed from her jaw, which turned out to be an extensive bone infection, and she enjoyed a well-earned rest after the surgery. On her return, she felt over the next few months that “God had made it clear that it was time for her to withdraw from CMC.” She submitted her resignation and on 31 August 1981, after 22 ½ years in India, she closed her office door for the last time. Some of the babies she had delivered in her early days were now returning as medical students. Eighty-four percent of the Diploma students and 29 of her MD postgraduates were using their skills in India rather than working overseas. The new head professor of the O&G Dept and five of the lecturers were all trained under Beryl.

On her arrival at CMC in 1959, the students were taught by an international staff including people from Switzerland, Germany, Canada, USA, Scotland and Ireland. On her departure, almost all the staff were Indian nationals, many of them graduates of CMC. Beryl had given priority to practical training along with the application of sound medical principles and modern needs of patients using and teaching methods of good care relevant to India. The graduates were not dependent on advanced technology as this would not be available in most of India in the foreseeable future. She was leaving CMC in good hands. (8)

Writing Textbook

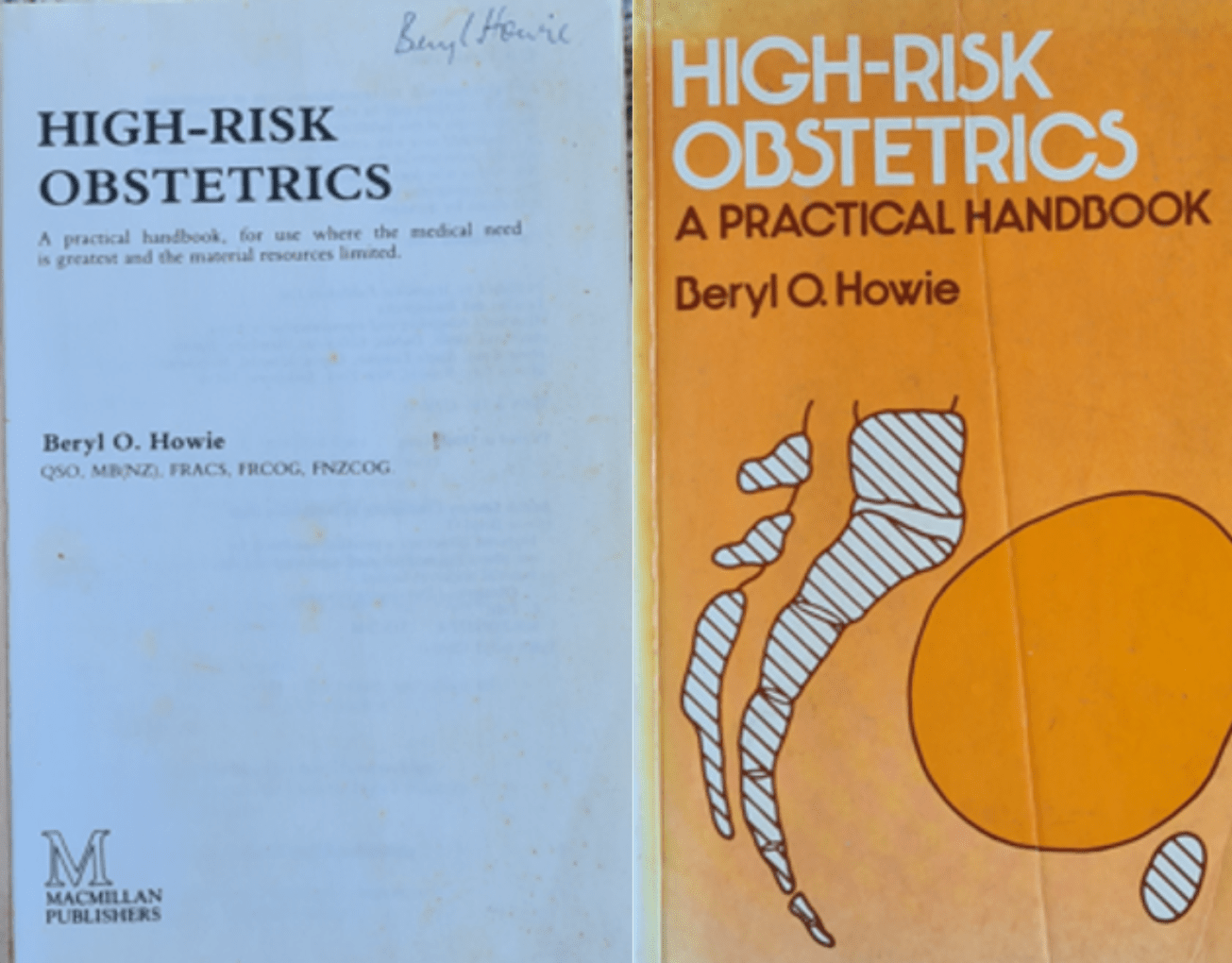

Following her departure from Ludhiana, Beryl enjoyed an extended time in the UK including time with her Stallworthy relatives. On her return to Auckland, Beryl found she was very tired. The previous two years had been exhausting. Her garden helped in her recovery as well as mentoring and praying with the students assigned to her at the Bible College of NZ (now Laidlaw College) and engaging in her love of chamber music. She was now fifty-six years old and retirement was not in her plans. She felt one way she could continue to serve the needs of the women of India was to write a text book for obstetric trainees which focused on the needs of women and babies in Third World situations. Her mission board was enthusiastic and granted her paid leave for the project. Over the next two years Beryl wrote ‘High Risk Obstetrics – a practical handbook for use where the medical need is greatest and the material resources limited’. (9) She worked from 9am to 5pm writing in long-hand – shaping the pages and chapters. MacMillan in the UK accepted the manuscript for editing and published it in 1986.

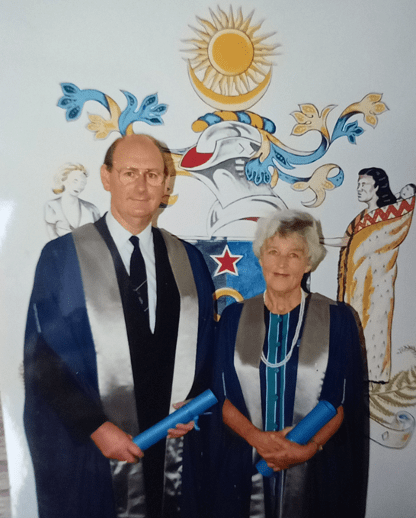

Also during this time, she joined the newly established Royal NZ College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RNZCOG) and in 1984, she was awarded an honorary fellowship from the Royal Australian and NZ College of Obstetricians Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). (10)

Bible and Medical Missionary Fellowship

While in India, Beryl had developed a close relationship with the Bible and Medical Missionary Fellowship (BMMF) which in 1987 became Interserve. Beryl had acted as their north India medical advisor for several years and more recently had become a member of the mission’s NZ council. They saw a need to improve the health care of its members in the Asia/Middle East areas, in particular to co-ordinate the health support of BMMF staff, and knew that it needed someone with a medical background. Beryl was approached and, when asked to consider the position of BMMF Medical Officer for Asia/Middle East, she quickly knew it was right for her. She was able to raise her support and in July 1984 travelled to their international office in New Delhi, quickly found an apartment a few blocks away, and set to work. Because of her connection with Ludhiana, she had never had visa problems in the past, but when seeking a renewal she was declined and in April 1985 had to leave the country within seven days’ notice. She packed her files into a tin trunk and it became her office over the next few months. Kathmandu became her temporary office but the international office eventually relocated to Nicosia, Cyprus in July 1985.

Beryl’s Asia/Middle East BMMF constituency comprised about 400 adults and 150 children under 18 years of age. They were mainly in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan, with smaller groups in Afghanistan, the Persian Gulf States, Egypt, and Lebanon. She began by establishing central health records and felt it was important to visit them to see how they were coping in their work environment, so several major trips were planned each year.

Over the five years until her departure from Cyprus in September 1989 Beryl travelled into many countries assessing the health needs of those under the umbrella of BMMF. During this period she developed a comprehensive health-care policy for missionaries which included medical screening of candidates and coordinated healthcare for those on furlough or retiring. She had developed the medical role and believed there was an on-going need for an international medical advisor, and she wrote a proposal to this effect. The directors of BMMF (all non-medical) considered and modified her recommendations and made it a part-time position. This was very disappointing to Beryl. However, many of her recommendations have now become standard practice among mission organizations.

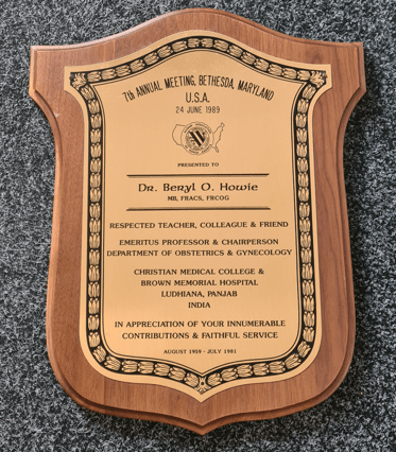

Just prior to her BMMF retirement, at its 24 June 1989 annual meeting, the USA Ludhiana CMC board presented her with the following recognition for her faithful service from August 1959 to July 1981:

On her final departure from Cyprus she travelled and met up with old friends and family in Europe, the UK, Canada and Australia before returning home on 9 February 1990 for her retirement years in Auckland. She was then sixty-five years of age. Soon after her arrival home she was made a honorary fellow of the RNZCOG.

Retirement Years

This was a time of major adjustment for Beryl after leading a busy, structured life since her primary school days. She wrote:

But the biggest adjustment is no longer having any definite role or daily schedule, to being no longer part of a busy work team. And having most of my previous close colleagues and friends scattered all the world! Quite a challenge, I’ve been very grateful for God’s help in all of this.

Beryl settled into the Victoria Avenue apartment which had been left to her by her mother. She loved her garden and enjoyed fresh lettuce, tomatoes and broccoli from it. She bottled peaches and pears. She made much needed repairs caused by a leaking roof and added a balcony on to it were she enjoyed many hours in the fresh air. She had closer times with her family helping with childcare when the need arose.

Her ten year old great-niece Rosalie interviewed Beryl for a school project. She concluded it with:

My great aunt says she is just an ordinary person but I think she is absolutely amazing and will never forget how helpful and kind to those people in India who needed her help. She always thinks of other people and never ever thinks of herself. I think she is a fantastic role model and I will always remember what she did and admire her.

Her niece Melissa described her aunt as humble, gentle, inclusive, kind, methodical, intelligent, a non-connoisseur of food – she was grateful for anything, who just kept doing what God wanted her to do throughout her life.

Arthritis in the base of her thumb from her years of surgery and writing the textbook made writing more difficult and “Lulu”, her laptop word-processor became part of her household and she learned to type. Her niece recalls “Bardy” telling her she was miraculously healed from the severe pain it caused her. A few years later she had a hip replacement. She attended her neighborhood Somervell Presbyterian Church in Remuera where she led Bible study groups and helped people learning English as a second language. She also led the Interserve mission prayer group in Remuera for many years.

Beryl found herself in demand as a speaker and with her wisdom and knowledge of international missions became a valued contributor on some mission boards as well as Tertiary Student Christian Fellowship, Christian Medical Fellowship and Missions Interlink Council. She enjoyed entertaining missionary friends and some of her ex-CMC medical students. In 1995, she was invited to attend the centennial celebrations at CMC but was disappointed she was unable to attend. However, at short notice at the end of 2000 she was invited to attend the Silver Jubilee Reunion of the CMC Ludhiana medical class of 1976. After 21 years, she enjoyed her five weeks back in India immensely. She was encouraged to see some of her students were now senior faculty members at CMC, others were serving faithfully in rural Christian hospitals, and many were involved in training others throughout India. In addition, she met many of the babies she had delivered during her time at CMC. Some of her impressions:

Fleeting and superficial of course. Population explosion indeed, chaotic road traffic – increased development sophistication for the better-off minority – aching need and apparently little change in the burgeoning slum areas. The continuing huge challenge to provide thoughtful and high quality people-care to the needy majority, along with God’s word of hope and new life and of the reality of His love. To ensure real access to relevant new medical technology, without inappropriate clinical dependence on hopelessly costly advanced methods which are quite out of reach of the big majority.

At the end of 2002 Beryl, a great communicator with a large world-wide group of loyal friends which included many of her former students, wrote that she felt the time was coming when she would not have further opportunities to chat with them and reiterated her gratefulness to God’s faithfulness in her own life and her desire to see them continue to serve Him faithfully.

In 2004, she was a recipient of the Epsom Girls Grammar School Old Girls Association (Inc) award for medicine (11) and on 20 May 2006 at the age of 81 years, Beryl was given an honorary doctorate from University of Otago. (12) In a press release, the Vice-Chancellor wrote:

Dr Howie exemplifies many of the finest qualities Otago seeks to instill in its graduates: personal commitment, the willingness to take up new challenges and a desire to improve the lives of her fellow human beings. The University of Otago is awarding an honorary degree to one of its graduates who has dedicated her life to serving women in developing countries.

In late 2010, Beryl contacted two long-term Christian pastoral friends, Paul Windsor and Marjory Gibson, and organized her own funeral with them. She was terminally ill with bowel cancer. In addition, her niece Melissa recalls she suffered from sensory deprivation which crept up her body to the level of her umbilicus. It was thought to be caused from heavy metal from the drinking water she had while in India. Beryl eventually moved from her Victoria Avenue home to the Caughey Preston Trust Home and Hospital. She died on 1 December 2012. She was sorely missed by her brother John, who became an oral surgeon practising and living in Remuera, and his three children, Jock, Melissa and Hamish. John died in 2019. Melissa recalls this was a difficult time for her father as his wife died after a five year illness in 2011 one year before “Bardy”.

In the NZ Medical Journal obituary, it recounts that some 200 came to Beryl’s memorial service in Ludhiana. In addition, former students, residents and registrars sent messages vividly recalling the competence, compassion and determination she modelled. These qualities and her commitment to people in need were based on her lifelong Christian faith, which was deep, personal and attractive. (13) In memory of Beryl, the Ludhiana CMC USA board raised money to purchase a laparoscopic set for the Dept of O&G which Beryl had founded. (14)

Marjory Gibson wrote in a postscript in Bartha Hill’s biography that, even during her last days of pain, her visitors would be warmly welcomed and Beryl would try to keep the focus on them rather than herself – bearing her suffering and loneliness with great courage, dignity, strength and humility. They were instructed that her funeral service was to acknowledge how God had led and provided for her through all the years. Beryl was self-effacing to the end – people could easily miss how radical a pioneer she had been in her field of medicine.

Bibliography

- Hill B. Teaching Hundreds to Heal Millions: The Story of Dr Beryl Howie. Tauranga, NZ: Daystar Books Ltd; 2013.

- Examination Results Waikato Successes. Waikato Times. 1914 22.01.1914. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WT19140122.2.45

- Wanhalla A. In/visible Sight – The Mixed-descent Families of Southern New Zealand. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books Ltd; 2009.

- Scholarship Winners. Southland Times. 1910 15.01.1910. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ST19100115.2.61

- Scholarship Examinations. Otaki Mail. 1943 25.01.1943 [09.02.2024]. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OTMAIL19430125.2.33

- Grant S. Vision for the Future – A Centenial History of St Margaret’s College, Dunedin 1911-2011. Dunedin, New Zealand: St Margaret’s College; 2010.

- Edith Mary Brown: Wikipedia; 2023 [updated 31.12.202309.02.2024]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Mary_Brown

- Dr Howie leaving Ludhiana. The Outlook. 1981 01-06.1981.

- Howie B. High-risk obstetrics : a practical handbook for use where the medical need is greatest and the material resources limited. London, UK: MacMillan; 1986.

- RANZCOG Honorary Fellow Recipients 1981 to 2009 Melbourne: RANCOG; 2009 [01.03.2024]. Available from: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Honorary-Fellow-Recipients-1981-to-2009.pdf

- Epsom Girls Grammar School Old Girls Association (Inc) Founders Awards Recipients Auckland: Epsom Girls Grammar School 2019 [09.02.2024]. Available from: https://www.eggs.school.nz/assets/Documents/OGA/fca1339114/OGA-Founders-Awards.pdf

- University of Otago Honorary Graduates Dunedin: University of Otago; 2019 [09.02.2024]. Available from: https://www.otago.ac.nz/alumni/people/honorary-graduates

- Troughton D, Troughton R, Laigesen M. Obituary Beryl Overton Howie. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2013;126(1370).

- Ludhiana CMC US Review: Beloved Professor Remembered. Columbia, Missouri: Ludhiana CMC Board USA; 2013 01.04.2013.