This biography is based on secondary literature written about Kathleen by close friends. The majority of the information comes from the chapter on Kathleen in Professor Manying Ip’s book on Chinese Women in New Zealand published in 1990, which is primarily a transcript of Manying’s interview with Kathleen in her Tauranga home. Kathleen’s studies and career were also widely documented in various newspaper articles throughout her life. All resources are listed in the bibliography.

CLASS OF 1929

Image of Kathleen Pih from the day of her ordination published in various newspapers to celebrate her return to China. (30)

Contents

Early Years in Antung, China

Pih Zhen-Wah, later known as Kathleen and affectionately known as Kay, was born on 10 June 1903 in Antung of the Jiangsu Province. (1) Antung, which is now known as Lin Shui, is located approximately 300 kilometres north-west of Shanghai. (2) (46) Her father gave her name, and it became a prophecy for her life. In Mandarin, Kathleen’s mother tongue, Zhen-Wah or Zhenhua means “to strengthen China”, and it is traditionally a male name. Her surname, Pih or Bi is “But” in Cantonese, “Bi” in the Peking dialect, and “Bik” in Shanghainese. Pih is the Romanised version of the name. (46) (47)

KATHLEEN’S FATHER

Kathleen’s father was a scholar who worked primarily as a Chinese teacher for missionaries. (2) He primarily taught missionaries from the China Inland Mission, and he would go to their houses to teach, preferring one-on-one classes to group sessions. (47) It was through this that he met Miss Margaret Reid, who was a member of this mission. (46) Kathleen’s father was a member of the gentry and consequently had land in the area. He also owned a medicine shop and Kathleen remembered watching him weighing herbs for his customers. He was a very formal, solemn man. Kathleen was one of four children. She had two brothers and one sister. Tragically, her sister and one brother died in childhood. Unfortunately, nothing is mentioned about Kathleen’s birth month in any of the documentation. (47)

MARGARET REID

Margaret Adams Reid was born in 1870. (39) Margaret worked as a teacher at a state school in Dunedin but felt the call to missionary work in China in 1894. (3) (38) She spent a total of twelve years in China on her first mission trip and returned with Kathleen later in her life. She had one brother, John Reid, who was a very well-respected man in the Otago region. He was also a teacher and was later appointed as the headmaster of Otago Boys’ High School in Dunedin. (47)

It was through her mission’s work that Margaret met Kathleen’s father, as he taught her the local language. ‘One day Aunty Maggie, that is what I came to call her, Aunty Maggie had her class and my father came. She asked, ‘Teacher, why are you so sad?’ My father replied, ‘My daughter is dying’.’ Margaret offered to look at her, even though she was a teacher, not a doctor. Kay was unconscious and had a weak pulse. She asked Kathleen’s father to sign a document saying that he would not blame her should Kathleen die since she was so far gone. And then she proceeded to help as much as possible. ‘I was so far gone then, she had to feed me p.r., per rectum, you know? She moistened my lips, I couldn’t swallow. She gave me donkey’s milk, buffalo’s milk, goat’s milk, and some glucose water, I suppose. She was a very resourceful woman. I revived. But it took a whole year’. (46) (47)

MEMORIES OF ANTUNG

Because Kathleen was sick with dysentery, she spent a lot of time with “Aunty Maggie” so that she could look after her. Indeed, most of Kathleen’s remaining memories of Antung were related to experiences she had with Margaret. Kathleen only attended school once in China and so never learnt the Chinese written characters. She also never had her feet bound, which she was always grateful for. ‘They usually started to bind a little girl’s feet when she was about three. I could remember how other little girls wailed and wailed when their feet were bound. Maybe they didn’t bind mine because I had been so very sick, or my parents were somehow more enlightened. I don’t know for sure.’ (47) She also remembered that the primary mode of transporting goods was with a wheelbarrow, which villagers even used to transport people around the town. Kathleen remembered going out with Margaret often, and she would ride in Margaret’s wheelbarrow to their destination. However, she did remember one time when Margaret fell incredibly ill, most likely with typhoid fever, and she was too sick to be transported by wheelbarrow. Four of the local men had to carry her in her bed all the way to the nearest hospital in Ts’ingkiangpu. (47)

Antung was surrounded by a city wall, and just outside the wall were many poppy fields that the locals would harvest to sell opium. There were also cherry blossom trees. Around 1906-7, there was a terrible flood which destroyed much of the area and led to a famine. ‘The refugees lived in caves along the river bank and all the bark off the trees in the village was gone, all eaten off. Miss Reid organized relief work. I remember all these men carrying mud from the river to fill up a pond in the mission ground. Then she would give them something, either rice or flour, at the end of the day.’ (47) She also remembered seeing lots of dead bodies and bones around the city wall.

TRAVELLING TO NEW ZEALAND

In the early 1900s, Margaret received a letter from her father asking her to return to New Zealand. His health was declining, and by this point she had been in China for almost ten years. Margaret was unsure what to do, though, since she was acting as Kathleen’s primary caregiver – she did not want to leave until Kathleen was stable. It was Margaret’s brother, John Reid, who suggested bringing Kathleen to New Zealand with her, and he even put in a personal request with the Governor-General, Lord Plunket. The application was complicated because people from China were considered “restricted entry aliens”. (2) The whole process from the beginning of their application to the time they finally left Antung was three years, meaning that Margaret had been in China for a total of twelve years. (3)

The boat for New Zealand left from Shanghai, and Kathleen’s father travelled with them from Antung to see Kathleen off. This was the last time Kathleen saw him. The boat stopped in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, and Sydney, Australia. Their layover in Sydney was one week long, and Margaret had to pay an entry bond of £100 each to ensure that they would not stay longer than the allotted time. (3) After the week, they boarded a steamer bound for Wellington. Kathleen and Margaret arrived in Wellington on 6 February 1908. (1) Kathleen was only five years old. In the newspaper, Kathleen was described as a ‘bright, intelligent-looking, ruddy-cheeked girl’. (3) (47) While they were in Wellington, Lord Plunket requested to meet Kathleen. The visit was pleasant, and during it, Lord Plunket asked what English name Zhen-Wah would adopt. Margaret suggested Kathleen in honour of Lord Plunket’s daughter, due to his help in allowing them entry to New Zealand. (2) (47) Despite changing her given name, Kathleen retained the last name Pih.

Childhood in the South Island

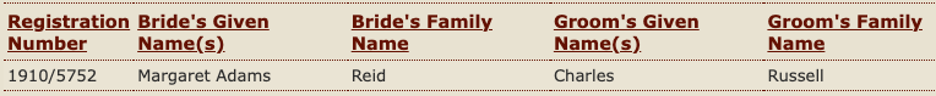

Margaret and Kathleen started off in Dunedin before moving to Waimate when Margaret married the widower Charles Russell. (46) He was a farmer, and his late wife had died of tuberculosis. She had been Margaret’s friend from before she went to China. Charles had two daughters with whom Kathleen got on well. She loved living on the farm and did not want to leave when the time came to do so. ‘I loved the countryside. I learnt to swim and how to ride a pony. There were many friendly neighbours.’ (47)

Kathleen’s love of the farm could have been linked to her experience as a Chinese woman living in Otago. ‘In those days it was really hard to be a Chinese person in Otago. It was quite demeaning… Of course I knew I was Chinese. I wished I wasn’t. It was all right when I was on the farm. But then in 1915 my aunt wanted to send me to the best girls’ high school in Otago. I was the only Chinese. They looked down on me, but in those days I would say that 99.99 per cent of people in Dunedin looked down upon the Chinese anyway… In those days in Dunedin there were a lot of Scots. Very few of them, I think, would feel that the Chinese were their equals. People in Dunedin were not very enlightened, they were not kind to the Chinese at all.’ (47)

Despite this, Kathleen performed well throughout her entire schooling years, which were well documented in the local newspapers. Kathleen started at Kirunga School in Roslyn. (4) On her very first day of school, the teacher asked Kathleen to read aloud. They made me read, ‘The cat sat on the mat.’ I chanted it out loudly and so impressed the teacher that she promoted me from Standard I!’ (47) In Standard I, Kathleen received a prize for first equal in the class as well as a prize for sewing. At the ceremony, she played a recital song. (4) Kathleen moved to Waimate Public School for Standard II, and once again received a prize in the prizegiving ceremony. This one was a special prize for steady progress. (5) Kathleen was still at Waimate Public School in Standard VI when she received a prize for industry. (6)

From Waimate, Kathleen continued on to Otago Girls’ High School, where she continued to perform well in all areas of her schooling. (2) (39) In 1915, she received a prize in sports for the class relay, which she completed with a time of 19 seconds. (7). In Form Five, she received a Navy League Essay Prize in the senior division. The theme of the essay was ‘The Part Played by British Sea Power in Winning the Great War’. (8) In Form Six, Kathleen received another Navy League Essay Prize as well as a special prize for hockey. Notably, Dr Winifrede Bathgate presented the class prizes at the ceremony. The newspaper reported: ‘Kathleen Pih was brought forward to receive a special prize, which, as Miss Allan said, was “a surprise,” this pupil getting the distinction for her consistent work as a hockey player.’ (11) On 27 January 1920, the newspaper announced that Kathleen had successfully achieved matriculation. She received M.S.P, which stood for graduation with Matriculation, Solicitors’ General Knowledge, and Medical Preliminary. (9) With this, Kathleen was able to start Medical Intermediate.

Throughout her schooling, Kathleen continued to experience racism. ‘In the girls’ school, the girls were just not too friendly. In the University too, the medical girls were really arrogant. There were so few girls, and they came from good families, from the moneyed class, and they really looked down on the Chinese. They were not nice to me at all.’ (47)

Kathleen’s decision to pursue medicine was highly influenced by Margaret’s aid work in China. Kathleen recalled that throughout her childhood, her father continually wrote to them in New Zealand. At some point, he requested her to return to Antung because she had been engaged to a boy since babyhood. Margaret prepared presents for Kathleen to take back with her, but as the time came closer, Kathleen decided she did not want to go; she loved the farm too much. ‘I was quite young then. Aunty Maggie said, ‘If you don’t want to go, you become a doctor, and then go. China has no women doctors, and they need women doctors’. That was how I made up my mind to be a medical doctor.’ (47)

Otago Medical School & House Surgeon Years

Little is known of Kathleen’s medical school years outside of what was reported in the newspapers. Since the announcement of Kathleen’s matriculation was published in January of 1920, she presumably began Medical Intermediate early in 1920. (9) However, the article in the newspaper that announced Kathleen had completed Medical Intermediate was only published in March of 1922. (12) It was not uncommon for women to take more than one year to complete Medical Intermediate, since many of the girls’ schools at this time did not teach the background knowledge required to succeed in this program. Perhaps this was also the case with Kathleen.

Kathleen potentially also repeated an early year in the medical program as she only completed her First Professional Exams in 1925. (14) However, she remained on track for the rest of her degree, completing her Second Professional Exams in 1926, and the first half of her Third Professional Exams in 1927. (15) (16) Following this, came her clinical years, and Kathleen graduated in 1929, making her the first medical graduate of Asian descent. (1) (2)

Throughout her time in medical school, Kathleen stayed at a missionary dormitory called Deaconess College. It was located in Dunedin North. Little else is known of her social life except for one article in the newspaper reporting that in 1925, Kathleen was one of three bridesmaids for Elizabeth John. The wedding was held at Musselburgh Presbyterian Church, so she most likely knew the couple through the church, as she was also a member there. Kathleen wore a ‘dress of shell pink French charmeuse trimmed with pink radium lace’. (13) The other notable thing to occur was in 1928 when Kathleen became naturalised in New Zealand. She was only one of two people of Asian descent allowed to be naturalised during the years between 1904 and 1951. (46)

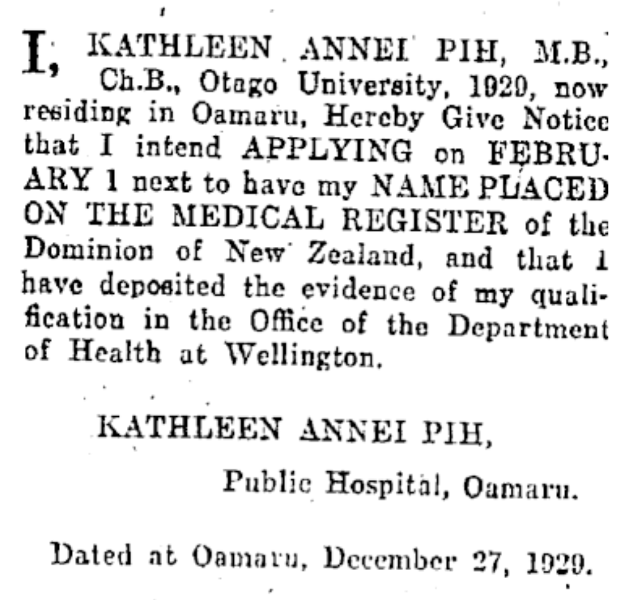

In June of 1929, Kathleen’s final year at medical school, the monthly meeting of the Waitaki Hospital Board confirmed Kathleen’s appointment as House Surgeon for Oamaru Public Hospital. (18) It appears that this appointment started shortly afterwards, as she finished her appointment as a House Surgeon the following March. At the end of 1929, Kathleen published her declaration that would be applying in February to have her name placed on the medical register, and Oamaru Public Hospital was listed as her hospital affiliation. (19)

Unfortunately, Kathleen continued to have issues in Oamaru, just as she had in Otago. She found that the medical men at the hospital were not friendly towards her so she mostly kept to herself. (47). Likewise, she recalled: ‘When I started as a house surgeon at Oamaru Hospital, some of the patients said, ‘We are not going to stay here if that Chinese doctor comes.’ But after I did arrive, they didn’t leave. At the beginning I was terrified, just terrified. They got to like me later on.’ (47)

On 10 March 1930, the Presbyterian Assembly met to discuss matters and announce updates, one of which was Kathleen’s intention to join the Canton Village Mission. (20) The plan was for Kathleen to complete her House Surgeon appointment and then return to Dunedin for Missionary Training College. After the assembly, the newspaper recounted the events that took place. The moderator introduced Kathleen to the audience and said, ‘It gives us peculiar pleasure to welcome this lady, whom the Assembly agreed heartily to send to China. It will interest the audience to know that this young woman is a native of China who has been educated in Dunedin, passed through the Dunedin Medical School, and is at the present time house surgeon in the hospital at Oamaru.’ (21) Upon the conclusion of her time in Oamaru, the St Paul’s Presbyterian Women’s Missionary Union invited her as a guest of honour to the monthly meeting. There, she was presented with a gift by the ladies of the union: ‘In presenting the guest with a handbag of New Zealand make, and containing a sum of money, Miss Patterson voiced the feelings of all present in wishing her much happiness and success in her work among the people of her own land.’ ‘Dr Pih, in acknowledging the gift, mentioned that the dream of her life since childhood was about to be realised, and she was looking forward to the commencement of her duties in her new sphere of service’. (22) Along with the handbag and money, Kathleen was given flowers and a medical book, ‘for which Dr Pih thanked her, saying how necessary such books would be in China, where she would not have the opportunity of conferring with other members of the medical profession.’ (25) (26)

Missionary Training College only lasted for a few months, and then Kathleen had her ordination ceremony on 8 September 1930 at St Andrews Church, Dunedin, before she set sail for Canton on 12 September. (23) In the message for her ordination, the Rev D. C. Herron remarked: ‘She would go back to China with some great advantages, but she would also be faced with certain disadvantages. She was going out with high hopes, but there would be times when she would probably be depressed by the indifference to religion in the country to which she was going. One of the greatest problems of the present day was how to meet the spirit of secularism, and she would probably find that very often she would have to maintain for herself the spiritual glow that was so essential. They would all follow Dr Pih with their prayers. So far as he knew, there had never previously been a ceremony of this kind in New Zealand, where a native of China, having gained the equipment and the inspiration of the Gospel in this country, felt called upon to go back to her own race. They would watch with interest the work which Dr Pih was going to do, and he hoped that when she was depressed she would remember that there were hundreds of people in New Zealand who would pray for her every day.’ (24)

The First Trip to China

Kathleen’s foster mother, Margaret, who was by this point widowed, decided to travel with Kathleen back to China. There she obtained a position as a lecturer of English at Sun Yet-sen University in Canton. (39) During their first year in China, Kathleen spent one year learning Cantonese. She took five classes every day in order to learn it as quickly as possible so she could return to work. (47) This was helpful as, when she began her work at Kong Chuen Hospital, the doctors very rarely spoke English to each other, even though they were primarily international people. The only time this would occur was to announce a patient’s death so that they did not upset the other patients in the ward. (47)

Even though her medical work was quite taxing, Kathleen lived a comfortable life. This was primarily because her wages were paid by the Presbyterian Church, and thus she earned a European salary. This equated to £150 per annum. (46) Unfortunately, this also made her feel quite emotionally uncomfortable because of the vast economic difference of the people she was caring for. (47) Many of her patients made their living by growing rice, peanuts, and yam, or raising fish. (47) She was affectionately called Dr Pat by her patients. (1)

Kathleen primarily worked out of Kong Chuen Hospital, where she stayed for five years. This hospital was run by New Zealand’s Canton Villages Mission and was located approximately 16 kilometres north of Canton city. (2) (46) The district covered by the hospital included around 100,000 people, and Kathleen was the only fully qualified medical practitioner at the hospital. Nevertheless, due to Chinese regulations, she was not allowed to head the hospital itself. (27) She had to do a lot of operations she had never done before simply because she was the most qualified. For example, she pulled quite a lot of teeth without anaesthetics, and she saw many sarcomas where the disease had been left untreated for so long it had made its way to the bone and thus needed to be amputated. She had to deliver a lot of babies too. Most of the time, mothers would give birth at home with the help of a midwife, but when there was a problem the midwife could not fix, the mother and baby were sent to the hospital. Unfortunately, the biggest problem was follow-up care, as it was difficult to educate the mothers about hygiene. Also, many babies died of tetanus if the midwives had used a dirty piece of tile or glass to cut the umbilical cord. But they had to use what was there. (47) ‘When I was a missionary doctor, I just went round the villages and did the ordinary things that every doctor does. There was a lot of typhoid fever, malaria, and beri-beri. Lots of renal and bladder stones. All sorts of amputations as well. I was never meant to be a general surgeon, but I did a lot of amputations. We went round the villages.’ (47) Three times a week, Kathleen also ran a discount clinic. Here, they only charged 5 cents for a consultation rather than the normal 50 cents.

‘They were rich, rewarding years… I really enjoyed my midnight calls … being carried in a bamboo chair on the shoulders of two men and under the most glorious moonlight.’ (46) Reflecting on her time there, Kathleen said: ‘I am really glad that I went back to China. As a girl, I did not like being Chinese at all. The people that I admired were the Scots. I accept that I am Chinese now, but I was very sensitive about it when I was young. Going back to work in China in the 1930s was really good for me, otherwise I would always have felt so sorry for myself for being born Chinese. Only after working in China did I find my Chinese identity’. (47)

In 1934, the newspapers in New Zealand reported that both Kathleen and Dr Tenny Howie (the uncle of Dr Beryl Howie) were working at Kong Chuen Hospital. There were also two New Zealand nurses, one from Oamaru and one from Auckland, and a New Zealand teacher was working at the local board school. (28)

Kathleen stayed at Kong Chuen Hospital for five years during this trip, and she was overall very happy here. Her life was dominated by her work, but she did take one trip that was not wholly focused on medicine. Kathleen travelled to Shanghai to attend a medical conference, but while there she organised to meet up with her brother. Unfortunately, at this meeting, she found out that her sister and other brother had died at a young age, and so they were the only two left from the family. People told Kathleen that she looked quite similar to her brother. He was working as a pharmacist, and they had to have an interpreter present so that they could speak with each other. From this meeting on, they continued to write to each other. Kathleen’s Chinese language teacher would help her translate the letter from her brother, and then she would dictate her reply to the teacher who would write it down in the characters. (47)

A Short Stint in London for Postgraduate Studies

In 1936, Kathleen left Kong Chuen for London, where she intended to pursue postgraduate studies. In July, it was reported in the New Zealand papers that she had passed the preliminary examination for postgraduate studies in Ophthalmic Surgery at Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital. (2) (29) (31) (46) Since this hospital was located in the Moorfield area, it was often referred to as Moorfield’s Eye Hospital (47) On her trip from Asia, she had first completed a short tour of the province of Angus and the city of Aberdeen with some New Zealand friends, Reverend G. S. and Mrs Brown. (32) She had then arrived around June and started the program a few months later. Her foster mother, now Mrs Russell, assisted her while she completed the course. She specialised in Eye, Ear, and Throat medicine. She received the Diploma of Ophthalmic Medicine and Surgery (D.O.M.S.) in 1937 and then returned to China. (47). Upon the completion of her course, the newspaper reported: ‘In recognition of her success the Chinese of Wellington have sent Dr. Pih 50 pounds for the purchase of medical instruments’. (34)

The Return to China and Marrying Francis

Early in 1937, Margaret and Kathleen returned to China to continue their missionary work. They initially attempted to visit Kathleen’s brother in Antung, but the rail company were refusing to travel south due to rumoured fighting in Shanghai. The two eventually managed to get passage on a Norwegian Coal Boat, but the morning after they landed in Shanghai, they found themselves surrounded by approximately 100 Japanese battleships. (47) They also saw planes dropping bombs on Shanghai. (2) Thankfully they managed to escape due to the intervention of the British Consulate, but that was the last time Kathleen ever attempted to return to the place of her birth. (47)

Kathleen and Margaret returned to Canton and continued their missionary work, where they remained until she married in August 1938. (33) Kathleen had met the doctor K. S. Francis Chang on holiday in the first year she returned to China. She was staying at a resort for officials and missionaries in the mountains, and he was staying in the house next door. The older lady he was staying with tried to play matchmaker with the two by inviting Kathleen over for afternoon tea but nothing initially happened. (47) However, in January 1938, the New Zealand newspaper announced that Kathleen had become engaged to Francis, stating that he was currently a Professor of Anatomy at St John’s University in Shanghai and that he was a member of one of the leading Christian families in China. (2) (35)

The couple were married on 15 August 1938, and Kathleen subsequently moved to Shanghai to join him on the staff at St John’s. (47) She found the University administration to be quite corrupt here. Even though it was an American-built university and thus had adequate funding, they only paid the Chinese staff on a Chinese payscale, which did nothing to help the poverty in the area. (47)

Everything changed, though, in 1941. After the attack on Pearl Harbour, the Japanese invaded Shanghai and took over many places, including St John’s University. At first, the staff were left to their own devices. Kathleen recalled:

I think it must be owing to the two wonderful Japanese supervisors sent to oversee us. The first one was Professor Seki. He was a perfect gentleman. He had a degree in law from Tokyo University, as well as a degree in theology from Cambridge, and of course he was an officer in the army. It happened that we lived in the same building. Francis and I lived on the third floor, and he lived on the first floor. At first, we tried to avoid him. Then he took to doing exercises on the veranda, bending and stretching, and always turned our way and said ‘Good morning’ when we passed by on our way to lectures. Then he invited us to go up to have a cup of tea. He spoke perfect English and served tea ‘in the Cambridge fashion’ by warming all three cups by pouring hot water into them first.

After Mr Seki came Mr Sakamoto. He was much older, and also a Christian as well as a scholar. Again we tried to be distant, but he always came up to borrow this and that, and when he returned anything he always brought a little gift. You know, some rice, or foodstuff and so on. Francis and I liked to walk in the moonlight around the campus. It was such a beautiful campus. Mr Sakamoto would walk around, too, often about the same time. We bumped into him this way. He was lonely, I think. Once he suddenly said, ‘I don’t approve of this war!’ Honest, wasn’t he? If anyone had heard him, he would have been in great trouble. (47)

During this time, the newspapers reprinted a letter sent from Kathleen to some friends in New Zealand:

‘“We are frequently awakened by gunfire between the guerrillas and the Japanese,” continues Mrs Chang. This place is patrolled by British soldiers who make a round every hour both day and night. At the gate, there is a mounted guard.’ ‘Now Shanghai to-day is a city of deadly crimes… Still the theatres are full, the restaurants are full, and on the surface people seem to have no cares, for there are so many ups and downs that the Chinese have developed the philosophical attitude not to take disasters and misfortunes too seriously. The school is packed with refugees. Some millionaires become beggars in a moment … It is now that so many have turned to religion and God for their solace and comfort and hope. Never in China has the Gospel been so eagerly received.’ (37)

Returning to New Zealand for a Break

Though the war eventually ended, the troubles did not cease. The couple decided to stay in Shanghai throughout the Second World War, the Civil War, and the subsequent communist takeover. (2) However, due to the corruption of the government and the inflation that was a result of the war, Margaret invited the couple to come out to New Zealand for a year to have a break. They ended up staying from 1946 to 1947, and Francis picked up a temporary teaching job at Otago Medical School. (2) (47)

I found that people were so much nicer to the Chinese. I’d say that in the 1940s, New Zealanders were a bit more enlightened. Quite a number of Chinese children came during the war, and they had excelled themselves in all fields. That must have made the New Zealanders think more highly of the Chinese. Although the social climate was easier, we never wanted to settle down here, not in the late forties. Francis always said that China needed him more. (47)

In 1946, Kathleen was invited as the chief speaker for a celebration in Otago for a Chinese National Holiday. 150 people of Chinese ethnicity travelled to Otago for the 34th anniversary of the Republic of China. (42) (43) In October of 1947, Kathleen also spoke at the monthly Otago High School Ex-Girls’ Association meeting. Her talk focused on her work in China over the 16 years that she was there. (44)

Occupation in Singapore and the Escape to Hong Kong

In 1947, the couple decided to return to Asia. At first, they moved back to Shanghai. (2) Kathleen recalled: ‘By the time we returned to Shanghai, the situation just got worse. Francis was paid one million Chinese dollars, but that was just equal to one US dollar. I was paid a little lower, $900,000. We were all ‘millionaires’, except that the millions could hardly buy anything. We really found it hard to live like that, just scraping on’. (47) Not long after they arrived, however, communists invaded the city. Despite the turmoil, the couple decided to stay at the university, which was caught in the crossfire. The Nationalists fought from one side of the campus while the Communists fought from the other. After three days of fighting, the Nationalists surrendered. (47)

The couple spent one year under Communist control but fled to Singapore a month before the border closed. They had to leave all their belongings behind. (46) ‘Mr Tucker, a good friend, had tried very hard to persuade us to leave, but we had always hesitated. Although Francis did in fact investigate about possibilities of our going to Singapore. Tucker was Professor of Mathematics and an American. On the eve of his own evacuation he came and saw us to persuade us to leave. Then he gave us this blank cheque before he left, saying, ‘In case you change your mind.’ We would never have dared to leave otherwise, you can’t go far on one US dollar anyway. We used some money to buy our train tickets and Mr Tucker’s cheque I had sewn up in my petticoat. We just slipped out of Shanghai. We went to lectures in the morning in the usual way. We had a very bad moment at the train station. We were stopped and searched by the police! They opened Francis’ cigarette case in which I had rolled up a Hong Kong $100 bill, and my heart nearly dropped. They didn’t notice and found the microscope which he dearly loved. Aunty Maggie had given it to him for a wedding present. Francis spoke to them in Mandarin and we were allowed to board the train’ … Back in Shanghai, no one had realized that we had escaped. For the university had no classes for four days, it was the Qingming festival. From [Singapore] we sent a telegram and all hell broke loose. They went into our apartment and took all our things, searching for incriminating evidence. We lost most of our possessions. That is why I have no photographs of my China days. (47)

They arrived in Singapore on the 1st April 1948, which was fortunate as, from May onwards, all people crossing the border needed to have a permit. (47) Francis obtained a position teaching anatomy at the University of Malaya. Kathleen was also offered a position teaching and they began to earn properly for the first time in a long time. (47) ‘The bursar of the University was very kind to us. ‘I suppose you have travelled very light,’ he said. ‘When did you leave Shanghai?’ He started Francis’ salary from the first of April although we did not get to Singapore till May. We could also have an advance of money for a refrigerator. We were so used to being poor in China that we were very nervous about money! Life in Singapore was very lovely, everything was beautiful: people so friendly and students so charming’. (47)

They spent five years in Singapore, during which time Francis was invited to return to Hong Kong to take up a position as Professor of Anatomy at Hong Kong University. (2) Francis was hesitant to accept due to the ongoing Korean War, but in 1955, two years after the end of the war, he finally accepted. The couple spent fourteen years here. Kathleen also taught at the University alongside Francis, but she also ran her own clinic and worked as a missionary doctor for two clinics under the Brethren Church. (2) Most of her work revolved around refugees from the Canton area. ‘Therefore it was actually two worlds that I lived in, the one in the ivory tower of the Hong Kong University and, at the other extreme, amongst the homeless and the destitute. It was a rewarding and satisfying experience, to be able to help people really in need. I saw miracles performed and real answers to prayer’. (47)

Remembered By All

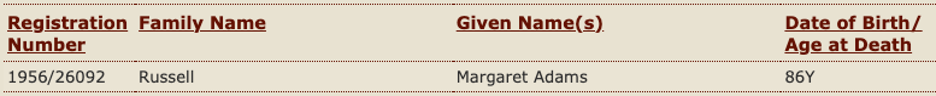

In 1969, when Francis turned 60, the couple retired and moved back to New Zealand. (2) (46) (47) They settled in Tauranga due to the community they found there, and Francis spent a lot of time developing their garden. He built a Chinese Garden with pines, maples, bamboo, rocks, cherry blossoms, a moon gate, and rocks he bought from the quarry. (47) Francis died in 1978, which Kathleen attributed to his bad habits: ‘He used to smoke over a hundred cigarettes a day, and drank coffee from six till after midnight’. (47) Kathleen continued living in their home until her own death on 22 February 1991, aged 87. (2)

She was fondly remembered by everyone she knew and worked with.

‘Pih Zhen-wah’s work and service in China fulfilled her name’s promise, just as Dr Kathleen Pih-Chang’s Christian faith and commitment to her profession have honoured this country. In all her other worlds too, she has graced the lives of everyone who knew her.’ (46)

‘Extremely modest and softly spoken, she carries herself with the fine sense of courtesy of a cultivated English gentlewoman. She is never over-formal or stiff though, and is always warm, sincere, and forthright… Such an air of gentle calmness and quiet dignity radiates from her as she sits talking or moves slowly around the house, however, that it is impossible not to recognize her strength of personality. She speaks quietly and philosophically, her round, slightly freckled face often lighting up with a strangely youthful and animated look when particularly vivid memories are stirred.’ (47)

Bibliography

- ‘150 Alumni Heroes’, University of Otago Magazine, 48, 2019, Otago.

- ‘Kathleen Anuei Pih-Chang’, Obituaries, New Zealand Medical Journal, 27 March 1991.

- ‘Little Pih. Romance of a Chinese Girl.’ Evening Post, 7 February 1908.

- ‘Schools Break-Up.’ Evening Star, 17 December 1908.

- ‘Waimate Public School.’ Press, 16 December 1910.

- ‘The Waimate Public School’. Waimate Daily Advertised, 18 December 1914.

- ‘School Vacations. Otago Girls’ High School.’ Otago Daily Times, 17 December 1915.

- ‘Navy League Essays. The Annual School Examinations’. Evening Star, 13 November 1919.

- ‘University Examinations’. Otago Witness, 27 January 1920.

- ‘Girls’ High School. Annual Break-Up’ Otago Daily Times, 18 December 1920.

- ‘School Vacations’. Evening Star, 18 December 1920.

- ‘Examination Results’. Evening Star, 30 March 1922.

- ‘Notes for Women. By Phillida. Personal and Social.’ Otago Daily Times, 25 August 1925.

- ‘University Successes’. Auckland Star, 9 December 1925.

- ‘N.Z. University’. Evening Post, 20 December 1926.

- ‘Medical School Exam Results’. Sun (Auckland), 10 December 1927.

- ‘Graduates of the Year. Degrees Conferred To-Day’. Evening Star, 18 July 1929.

- ‘Provincial News’. Otago Daily Times, 19 June 1929.

- ‘Advertisements’. Otago Daily Times, 30 December 1929.

- ‘Presbyterian Assembly’. Auckland Star, 10 March 1930.

- ‘Presbyteran Church General Assembly’. Evening Star, 11 March 1930.

- ‘North Otago’. Otago Daily Times, 23 May 1930.

- ‘Social and Personal’. Wanganui Chronicle, 19 August 1930.

- ‘Chinese Missionary’. Evening Star, 9 September 1930.

- ‘Chinese Lady Doctor’. Wanganui Chronicle, 15 September 1930.

- ‘Dr Kathleen Pih.’ Evening Star, 10 September 1930.

- ‘Down Petticoat Lane.’ Wanganui Chronicle, 6 October 1930.

- ‘China To-Day. A Missionary’s Work’. Otago Daily Times, 5 February 1934.

- ‘Social Items From London’. Evening Star, 23 May 1936.

- ‘Dr Kathleen Pih who was ordained last week prior to her departure from Dunedin to engage in mission work in China.’ Otago Witness, 16 September 1930.

- ‘Mission Enterprise’. New Zealand Herland, 11 July 1936.

- ‘The Social Round’. Southland Times, 13 June 1936.

- ‘Church Activities. Presbyterian Missions.’ New Zealand Herland, 26 February 1937.

- ‘Local & General News’. Timaru Herald, 26 April 1937.

- ‘Chinese Engagement. Medical Missionary’. New Zealand Herald, 21 January 1938.

- ‘Air Raid Damage’. New Zealand Herald, 21 January 1938.

- ‘Life in Shanghai.’ Otago Daily Times, 15 August 1939.

- ‘Fears for Safety’. Otago Daily Times, 14 March 1942.

- ‘Chinese Doctor’. Waihi Daily Telegraph, 15 January 1943.

- ‘Personal and Social’. Otago Daily Times, 14 April 1944.

- ‘News of the Week’. Lake Wakatip Mail, 8 August 1946.

- ‘Chinese Celebrate Anniversary of Republic. Picnic at Outram’. Otago Daily Times, 11 October 1946.

- ‘Successful Picnic’. Evening Star, 11 October 1946.

- ‘High School Ex-Girls’. Otago Daily Times, 24 April 1947.

- ‘Dr Francis Chang’. Otago Daily Times, 29 April 1950.

- ‘Kathleen Anuei Pih-Chang’. Margaret Maxwell.

- ‘The Story of Kathleen Pih-Chang’, in Ip, Manying, Home Away from Home: Life Stories of Chinese Women in New Zealand, New Women’s Press, 1990, pp.28-49.